|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

DAF YOMI

|

|

THE TALMUD: WHY HAS A JEWISH LAW BOOK BECOME SO POPULAR?

BBC Worl d Service, William Kremer, 8 November 2013

The Talmud, the book of Jewish law, is one of the most challenging religious texts in the world. But it is being read in ever larger numbers, partly thanks to digital tools that make it easier to grasp, and growing interest from women - who see no reason why men should have it to themselves.

Step into the last carriage of the 07:53 train from Inwood to Penn Station in New York and you may be in for a surprise. The commuters here are not looking at their phones or checking the value of their shares, but peering down at ancient Hebrew and Aramaic text and discussing fine points of Judaic law.

It's a study group on wheels, and the book absorbing their attention in between station announcements is the Talmud - one of the most challenging and perplexing religious texts in the world. The group started 22 years ago, to help Long Island's Jewish commuters find their way through the "book", which stretches to well over 10 million words across 38 volumes.

In his book, the Complete Idiot's Guide to the Talmud, Rabbi Aaron Parry says that when, shortly before his death, Einstein was asked what he would do differently if he could live his life again, he replied without hesitation: "I would study the Talmud."

It contains the foundations of Halakha - the religious laws that dictate all aspects of life for observant Jews from when they wake in the morning to when they go to sleep at night. Every imaginable topic is covered, from architecture to trapping mice. To a greater extent than the other main Jewish holy book, the Torah, the Talmud is a practical book about how to live.

"The laws are very, very relevant to everyday life," says Eliezer Cohen, a real estate manager who organises the classes on the train with a couple of other amateur scholars. "Many times, I go to the office afterwards and I'll get questions on current events or in business and I'll say, 'Oh, we just learnt that today in the Talmud.' It's a blueprint for life."

But the Talmud is perhaps better described as a prompt for discussion and reflection, rather than a big book of Do's and Don'ts.

"The Talmud is really about the conversation and the conversation never ends," says Rabbi Dov Linzer, of the Yeshivat Chovevei Torah School in New York. It is a distillation not just of oral law, but also the debates and disagreements about those laws - with different rabbinic sources occupying a different space on the Talmudic page. Mixed in with it all are folk stories and jokes.

At one time, tackling this most forbidding of texts was restricted to male scholars ready to devote themselves to prolonged study in a yeshiva or religious school. Then, in 1923, a rabbi named Meir Shapiro introduced a study regime known as daf yomi, or "page-a-day". Under the supervision of a teacher or a fellow student who has prepared in advance, students read through two facing pages of Talmud and commentary, try to work out the meaning and discuss the implications for their lives.

When the commuters of Long Island struggle over a difficult passage of Talmud, they know that tens of thousands of Jews all over the world are on the same page. And when he travels abroad, Eliezer Cohen can usually find a local group to continue his studies. On one trip to Jerusalem, he even encountered a man who, like him, taught the daily reading on his way to work (although on a bus, rather than a train).

Anatomy of a Talmudic page

Anatomy of a Talmudic page

1. Mishnah

Readers of the Talmud look at this part of the page first. It captures the ancient oral law of the Jewish people. Around the year 200AD -when Roman persecution threatened to break the spoken tradition - the leader of the Jews, Rabbi Judah the Patriarch, took the step of ordering the law to be distilled into a text to be memorised. "Mishnah" means repetition. It is written tersely in the form of short rulings in a language known as Mishnaic Hebrew.

This, the first page of the Talmud, deals with Jewish obligations of prayer and blessings, for example before and after food.

2. The Gemara

The Gemara, which in Aramaic means "to study and to know" is a collection of scholarly discussions on Jewish law dating from around 200 to 500AD. The discussions pick up on statements in the Mishnah (1) but refer to other works including the Torah. The Mishnah and Gemara combined constitute the Talmud as it is strictly understood.

The Gemara is written in Aramaic, and like the Mishnah lacks punctuation. However, there is a structure to the prose. Usually there is a statement, questions on that statement, answers and proofs. But rarely are the questions fully resolved.

3. Rashi

Students generally look at this section after reading a few lines of the Mishnah and Gemara. Rashi is a shorthand way of referring to Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, an 11th Century French scholar. He wrote one of the first complete explanatory commentaries on the Talmud.

Rashi's words are usually rendered in a special font known as Rashi script and always appear on the inside margin of the page.

4. Other commentaries and glosses

The rest of the Talmudic page is taken up with commentaries by other rabbis from the 10th Century onwards. One section - the Tosafot, or "additions" - deals with difficult passages and apparent contradictions in the Talmud. Another section provides cross references to identical passages elsewhere in the work, and another directs the reader to rulings in medieval Jewish law that relate to that section of the Mishnah (1) and Gemara (2). There is also room for modern explanations and glosses on the language.

5. Pages and chapters

The Talmud comprises six orders, which deal with every aspect of life and religious observance. It is further divided into 63 parts, or tractates, which are broken down into 517 chapters. This particular page is the first chapter of the first tractate in the Talmud, named Berakhot or "Blessings". It is page two of the Talmud - the first page after the title page. In fact, it is referred to as 2a - the facing page will be 2b.

Chapter names are taken from the first word of the Mishnah (1), which is also shown in large font in an illustrated box. In this case the word is mei'mata or "From when" – the complete first line of this first chapter of the Talmud is "From when should we recite the Shema ('Hear O Israel) in the evening time?"

Going through the text a page a day, the book takes seven-and-a-half years to complete - a moment that is eagerly anticipated and celebrated with an event called Siyum Hashas.

Attendance levels at Siyum Hashas events illustrate the Talmud's growing popularity. In 1975, the completion of the seventh cycle was marked by an event in New York's Manhattan Center with 5,000 attendees. In 1990, some 20,000 people in the US took part in the event and in 2012, at the completion of the 12th cycle, all 90,000 seats at the MetLife Stadium in New Jersey sold out for the event.

"It's clearly exploded in the last 10, 20 years, I think mostly through the number of people involved in the daf yomi project," says Dov Linzer.

And with each daf yomi cycle, the Talmud gets more accessible. Modern students can avail themselves of podcasts and round-robin emails from top scholars, and discuss difficult passages in online chat-rooms. A big moment came in 2005, with the publication of the first complete English-language edition of the work for more than 50 years, the Schottenstein edition. But there is no need to lug a giant volume around with you - the publisher, ArtScroll, is one of a number of organisations to have launched a Talmud app.

Since its launch last year, users have made around 15 million downloads, mostly of entire Talmudic volumes, Mayer Pasternak, director of Artscroll's Digital Talmud, told the BBC. To put that in perspective, the Jewish world population is thought to be a little under 14 million.

Pasternak says the Talmud is peculiarly suited to a digital treatment.

"It's a web of interconnected ideas and thoughts and commentaries," he says. "In one place something might be very poorly elaborated and you'll find in another place in the Talmud it's discussed at length - there's a constant cross-referencing process. We have about a million links in the digital app and we have a team of scholars putting the links in."

He adds that a social shift is under way. "A lot of the people that are interacting with us are women," he says. "It's obvious that they've heard about the Talmud and they're studying the Talmud."

For many Orthodox Jews, Talmudic study by women is seen as at best unnecessary and at worst, highly undesirable.

Gila Fine, editor-in-chief of religious publisher Maggid Books in Jerusalem, recalls that in her Orthodox school girls were not taught the Talmud. "As a teenager, I would often have these religious debates with my counterparts about various things in Judaism," she recalls. "And every single such argument ended with one of the boys throwing at me: 'Oh it's in the Talmud - you wouldn't know.' And that was it! I could never win an argument ever, because it stopped beyond the covers of this book, which I could not enter."

When she was 17, she secretly pulled a volume of Talmud down from her father's shelf, but was too scared to open it. "I stood there waiting for that lightning bolt to strike me down," she says. It was only later on, when Fine was at a progressive women's seminary, that she read the book properly.

Before you read the Talmud...

Image copyrightRABBI BRAWER

The core tracts in the Talmud lack punctuation and are written in a terse, telegrammatic style in Aramaic and Hebrew. Multiple inferences are possible, as Rabbi Naftali Brawer makes clear in this parable.

The core tracts in the Talmud lack punctuation and are written in a terse, telegrammatic style in Aramaic and Hebrew. Multiple inferences are possible, as Rabbi Naftali Brawer makes clear in this parable.

A young man goes up to a Rabbi and says "Please explain the Talmud to me."

"Very well," replies the Rabbi, "but first, I'll ask you a question. If two men come down a chimney and one comes out dirty, and the other comes out clean, which one washes himself?"

"The dirty one," answers the man.

"No," says the Rabbi. "They look at each other and the dirty man thinks he's clean and the clean man thinks he's dirty, therefore the clean man washes himself. Now, another question. If two men climb up a chimney and one comes out dirty, the other comes out clean, which one washes himself?"

The young man smiles and says, "You just told me, Rabbi. The man who is clean washes himself because he thinks he's dirty."

"No," says the Rabbi. "If they each look at themselves, the clean man knows he doesn't have to wash himself, so it's the dirty man who washes himself. Now, one more question. If two men come down a chimney and one comes out dirty, and one comes out clean, which one washes himself?"

"I don't know, Rabbi. Depending on your point of view, it could be either one."

Again the Rabbi says: "No. If two men climb up a chimney, how could one man remain clean? They're both dirty, and therefore they both wash themselves."

Scratching his head, the confused man says: "Rabbi, you asked me the same question three times and you gave me three different answers. Is this some kind of a joke?"

"This is not a joke, my son. This is Talmud."

She was profoundly disappointed. Unlike the lofty, magisterial prose of the Torah, she found the Talmud to have "all the imperfections, the trivialities, the multiplicity of voices, the wild associations - everything that characterises human conversation."

But Fine eventually fell in love with the book and is now overseeing the publication of a new edition. She relates in particular to the Aggadah, the folkloric stories in the Talmud, which rub shoulders with the dense, legalistic Halakha text, and seem sometimes to subvert it.

"You have stories of women who criticise men, of non-Jews who put Jews to shame, of poor simple folk who make a mockery out of rabbis - there's something very liberated and liberating about Aggadah," she says.

It was just such a story that was read out in the Israeli parliament in February this year. Knesset member Ruth Calderon's 14-minute long maiden speech began with autobiography, as she described her Zionist upbringing and the "void" she had felt at not being able to read the Talmud as a girl. "I missed depth," she said. "I lacked words for my vocabulary, a past, epics, heroes, places, drama - stories were missing."

It was just such a story that was read out in the Israeli parliament in February this year. Knesset member Ruth Calderon's 14-minute long maiden speech began with autobiography, as she described her Zionist upbringing and the "void" she had felt at not being able to read the Talmud as a girl. "I missed depth," she said. "I lacked words for my vocabulary, a past, epics, heroes, places, drama - stories were missing."

Then came a gesture which Fine describes as marking a profound cultural shift in Israel - Calderon opened a volume of Talmud. After reading the Aramaic, she embarked on a word-by-word textual analysis of a story about a rabbi who became immersed in his studies, and his wife who waited for him to return home. As a tear falls from the wife's eye, the roof that the rabbi is sitting on to study collapses underneath him and he falls to his death.

Calderon says the story was a comment on the rifts in Israeli society, and that the self-righteousness demonstrated by the rabbi in the story was something everyone could fall into. The key thing was the ability to see another's point of view - an ability central to being able to read the Talmud.

"Both sides of any disagreement are usually right in their own way," she says. "Both of them have a point. Judaism does not belong to any one side."

But the speech went viral and prompted frenzied editorials in the Jewish press - some of them critical.

This is partly because Calderon is a figurehead for secular Judaism, and sharply at odds with Israel's ultra-Orthodox community.

In the ultra-Orthodox yeshivas, scholars receive a stipend to study the Talmud, and are exempt from paying taxes and performing military service. Calderon opposes this - she came to the Knesset as a member of the Yesh Atid party, which polled unexpectedly well this year on a policy of "sharing the burden" (the burden of tax and military service).

Equally unpalatable to some ultra-Orthodox, Calderon opened the first liberal yeshiva, where women and non-believers are welcomed to study texts deemed important to Hebrew identity. It is said that about 100 liberal study halls now operate in Israel.

The Talmud is also making its mark in wider Israeli society in other ways. It increasingly appears in leadership courses, in newspaper columns and TV shows. A recent series of talks at the National Library, where Calderon used to be head of Culture and Education, asked a series of well-known personalities to discuss Talmudic passages.

Calderon points out that the increased popularity in Israel of Aramaic-sounding names like Alma is a testament to the resurgent popularity of the ancient text.

"The Talmud kind of goes with hipster culture," she says. "It's more laid back. While the Torah is more about wars and kings, the Talmud is domestic. I want the best people - the writers, the poets, the scriptwriters for TV - the people who are making Jewish culture [to read it].

"The secular elite that gave it up for many years are reclaiming it."

Gila Fine says that she wants the Talmud to be in every Jewish home and to be read by every Jew - male and female - but adds that there will always be a role for the Talmudic scholar who devotes a lifetime's study to the most complex and intricate tractates.

"This book is actually pulled out when you have to make a legal decision in Jewish law," she says. "You need specialists in the field. It's like saying: 'Do you want everyone to be dabbling in theoretical mathematics?' I may love theoretical mathematics, I may think that it's hugely important and everyone should be aware of theoretical mathematics, but I will also understand that to be in any way workable you really have to leave it to the experts."

Video by Anna Bressanin. You can listen to Heart and Soul on the BBC World Service. Listen back to the two-part series The Talmud via iplayer or browse the Heart and Soul podcast archive.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine on Twitter and on Facebook

Clarification: An earlier version of this story did not make clear that the story about Einstein's regret at having failed to study the Talmud was drawn from a book by Rabbi Aaron Parry.

The Talmud: Big in Asia

The Talmud is the subject of an unlikely publishing fad in China, Isaac Stonefish reports

Playing to stereotypes, the titles include Crack the Talmud: 101 Jewish Business Rules and Know All of the Money-Making Stories of the Talmud

The rooms in the Talmud Business Hotel in Taiwan each contain a copy of The Talmud-Business Success Bible

Young Sam Ma, South Korean ambassador to Israel said on a TV show that "each Korean family has at least one copy of the Talmud" because, he claimed, 23% of Nobel Prize winners were Jewish

ArtScroll says its English Talmud app has been downloaded around the world but it has not received any "serious enquires" about an edition in Korean

DAF YOMI: SIGN UP NOW FOR THE BIGGEST SIMCHAH ON EARTH

This online daily study plan could be the most positive thing to happen to Jewish-themed Google searches.

Jewish Chronicle, Yoni Birnbaum Rabbi of Hadley Wood Synagogue (London)

Google the words, "largest mass Jewish event worldwide" and the algorithm produces some very disturbing results. The first three alone are Wikipedia entries for "list of genocides by death toll", "pogrom’"and "timeline of antisemitism". By way of contrast, replace the word Jewish with Muslim or Christian, and the top results relate to the annual gathering for the Hajj in Mecca and record-breaking millions attending Catholic Mass in far flung corners of the globe. So, here’s the critical question. Will an equivalent mass Jewish event ever take place with the power to change these negative algorithms? Could something happen in the Jewish world on a scale able to top the Google search results?

Believe it or not, there are grounds to suspect that this may happen at the start of next year. For the past seven years, thousands of Jews worldwide have taken part in a daily study programme known as the Daf Yomi. Initiated in 1923 by the inspirational Rabbi Meir Shapiro of Lublin, the programme involves the daily study of a double-sided page of Talmud. As there are 2,711 of these pages in standard editions of the Babylonian Talmud, every seven and a half years the worldwide cycle is completed, leading to mass siyyumim, or celebrations of completion. The largest and most dramatic of these will take place on January 1st 2020 at the MetLife Stadium in New Jersey and is expected to attract nearly 95,000 people. As mass Jewish events go, that’s pretty impressive by any standards. Here in the UK, Wembley Arena will play host to a grand British siyyum a week later.

I have been a major fan (of Daf Yomi, not the Mets) for many years and am privileged to give a Daf Yomi shiur at Barnet United Synagogue. Time and again, I have witnessed the manner in which this remarkable initiative has deepened people’s connection to their faith, and the Jewish people, in unimaginable ways. Why talk about it now, seven months before the event? Because Daf Yomi is a major commitment. And if you are interested in joining what has been described as the world’s ‘"largest Jewish book club" — you had better start preparing now.

So here’s what you need to know. The Talmud is the single most important repository of Jewish teachings which guide the manner in which Judaism is lived, experienced and practiced today. It is the home of the famous rabbinic debates and discussions, buttressed with innumerable personal stories and anecdotes, which bring Jewish law and lore to life. Although it is often difficult to understand and contains extensive legal discussions on the finer points of Jewish law, studying the Talmud rewards you with incomparable insights into the Jewish story and the richness of our collective Jewish heritage. Most importantly of all, the Daf Yomi project is a wonderful Jewish unifier. When launching it in 1923, Rabbi Shapiro described how as a result of his idea, a Jew could travel for 15 days from Israel to America (by boat!), learn the Daf each day, and enter a shul in New York to find a group of fellow Jews learning the very same page he had studied that morning. "Could there be a greater unity of hearts than this?", exclaimed Rabbi Shapiro.

Knowing the time commitment before you think about taking the Daf Yomi plunge is important, however. To study with any real level of understanding, you need to dedicate about 45 minutes a day to it. I would also strongly advocate joining a daily Daf Yomi class in a local shul, or if that isn’t possible, choosing an online one, something you can experiment with in advance. Outstanding English translations of the Talmud, such as those produced by Artscroll and Koren, have also helped make the text more accessible than ever before.

This weekend we celebrate Shavuot, which commemorates the Sinai experience and the start of our relationship with the Torah. Many have the tradition of staying awake all night in order to study. Come next January, an estimated 200,000 people worldwide will take part in the single greatest mass Jewish event on the planet, centred around that very tradition of learning we share. This is obviously a cause for celebration, as well as an opportunity to change depressing Google algorithms. But far more significantly, it will hopefully inspire more people to expand their commitment to Jewish learning beyond that of the annual Shavuot experience.

This is our Talmud, our text and our tradition. We should all own it. My only piece of advice is — start planning now!

MEET THE NON-JEW WHO MADE DAF YOMI POSSIBLE

Daniel Bomberg capitalized on the disruptive new technology – printing, understanding the potentially huge market for books amongst Jews.

Aish Dr. Henry Abramson This article originally appeared on Ou.org July17, 2019

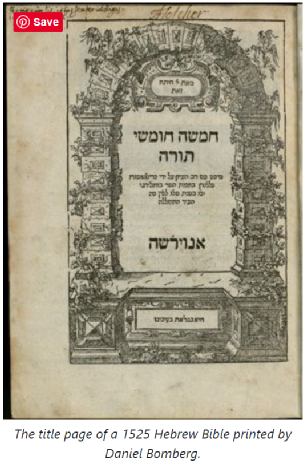

People are familiar with Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who initiated the Daf Yomi worldwide phenomenon where Jews around the world learn the same page (daf) of Talmud. But does anyone ever think of Daniel Bomberg, the Christian who literally put the “daf” in Daf Yomi?

People are familiar with Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who initiated the Daf Yomi worldwide phenomenon where Jews around the world learn the same page (daf) of Talmud. But does anyone ever think of Daniel Bomberg, the Christian who literally put the “daf” in Daf Yomi?

Rabbi Shapiro’s brainchild was born in 1923, a time much like our own. As powerful political, social and economic forces exerted a centrifugal force on the Jews of that era, Rabbi Shapiro understood that the shared study of the Talmud, a core Jewish text, was a powerful way of bringing the fractured Jewish people together under the umbrella of our long intellectual and spiritual tradition. Since then, his innovative program, as boldly ambitious as it was elegantly simple, has united Talmud enthusiasts from Lakewood to London, from Hebron to Hong Kong – literally anywhere in the world, one can find a class that is literally keeping Jews around the world on the same Talmudic page, every single day.

Rabbi Shapiro’s brilliant idea, however, could not have occurred without the signal contribution of one Daniel Bomberg.

Born in Antwerp in the late 1400s to a middle-class family of printers, Bomberg received a decent liberal arts education that even included a smattering of Hebrew. This served him in good stead when he went to make his fortune in the bustling metropolis of renaissance Venice, home to a mercantile Jewish population that was recently restricted to the Ghetto.

Printing was in its infancy, but Jews were among the early adopters of this disruptive new technology. The Soncino family were producing beautiful editions of individual Talmudic tractates, confident that the lower production costs of printed Judaica would place books in the reach of average families. Known for their scholarship, the Soncinos took great pains to produce works of lasting quality – but they simply couldn’t print their tractates fast enough to meet the demand.

This is where Bomberg saw his opportunity. Assembling a group of Jewish scholars, beginning with Jews who had converted to Christianity, Bomberg rapidly churned out printed versions of Jewish classics such as the encyclopedic Mikra’ot Gedolot edition of the Torah. The early editions were plagued with errors, and many readers resented the use of apostates in their preparation, but Bomberg had accurately judged the market: the people of the Book wanted lots more books, especially the Talmud, and the demand far outpaced the leisurely supply of the Soncino family of printers.

This is where Bomberg saw his opportunity. Assembling a group of Jewish scholars, beginning with Jews who had converted to Christianity, Bomberg rapidly churned out printed versions of Jewish classics such as the encyclopedic Mikra’ot Gedolot edition of the Torah. The early editions were plagued with errors, and many readers resented the use of apostates in their preparation, but Bomberg had accurately judged the market: the people of the Book wanted lots more books, especially the Talmud, and the demand far outpaced the leisurely supply of the Soncino family of printers.

Bomberg soon replaced his early staff of Jewish Christians with well-regarded Rabbinic scholars straight out of the ghetto. As a Christian, he was also able to negotiate favorable terms for his business, including the right for minimal Church censorship, arguing that ancient texts required preservation in their original state. He even secured rare privileges for his Jewish staff, such as an exemption from the requirement to wear the humiliating Jewish hat.

Bomberg shamelessly copied the Soncino design, with the commentary of Rashi on the side closest to the spine and Tosafot on the outside of the page, and added one important change: page numbers.

In a spurt of remarkable productivity, the Bomberg printing house produced a fantastic number of Hebrew books, including the first full printed edition of the Babylonian Talmud. He shamelessly copied the Soncino design, with the commentary of Rashi on the side closest to the spine and Tosafot on the outside of the page, and added many innovations of his own, including one especially important change: page numbers.

Yes, page numbers. As text-oriented as Jews are, we simply never got around to inventing basic pagination (we also lagged behind in punctuation, and as anyone who struggled to learn modern Hebrew knows, we weren’t so hot at vowels, either). Looking at the rapidly evolving conventions of 15th-century printing, Bomberg added a letter “bet” to the first page of text in Tractate Berakhot of his second edition of the Talmud – and the Daf was born.

Since then, much rabbinic and scholarly ink has been spilled in vain, struggling to understand why he didn’t begin with “aleph,” the first letter of the alphabet. The simple explanation is that Bomberg considered the title page as the first folio, or page one.

Although it seems obvious in retrospect, Bomberg’s brilliant introduction of page numbers ultimately set the standard for every single Daf in virtually every single printed edition of Talmud for the next half-millennium. If a given word is on a Bomberg page, it should be on the same page in every future Talmud. Future printers adopted this standardized allocation of precise passages to every page, and there was no messing with Bomberg: even the great contemporary scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz was roundly excoriated in certain circles for altering the traditional page layout in his award-winning edition of the Talmud.

Yet by standardizing the Daf, Bomberg made possible the notion of an international, coordinated study of the Talmud. Rabbi Shapiro literally couldn’t have done it without him.

There’s one basic takeaway message to this story: when tens of thousands of Jews crowd together in January 2020 to celebrate another cycle of Daf Yomi – last cycle, nearly 100,000 Talmudists packed Met Life stadium, and this cycle will likely be bigger – we should recall not only the phenomenal dedication of the Daf Yomi students and teachers, and not only the inspirational message of unity through study proposed by Rabbi Shapiro’s vision, but maybe we should give some credit to the blessing of a philosemitic Christian from Antwerp, Daniel Bomberg.

This article originally appeared on Ou.org

Jewish History in Daf Yomi | Henry Abramson 5 Jul 2019 - Jewish History in Daf Yomi, a project of the OU Daf Yomi Initiatives of brief videos (2-5 minutes) on historical subjects related to the specific page in the Daf Yomi program of Talmud study. At present over 150 videos are online at www.ou.org/dafyomi and in the OU Torah App, and will be featured in AllDaf, a new App currently under development. In the meantime, the growing number of videos (a total of 2,711 are projected) are serviced by this rudimentary index.

How to Use the Index:

In a separate window, open up www.ou.org/dafyomi.

Click here to open up the General Index (alphabetized by topic).

Alternatively, click here to open up the Subject Index (alphabetized by subject: Biography, Culture, Economics, Geography, Medicine, Numismatics, Technology, The Talmudic Page, Weights and Measurements).

Note the Tractate and Daf of the desired video.

Return to www.ou.org/dafyomi and select the Tractate and Daf from the drop-down menu.

Enjoy the videos in good health!

Daf Yomi & Shas by Real Clear Daf - Apps on Google Play RealClearDaf.com's famous Daf Yomi shiurim have been neatly arranged in this highly intelligent Torah app! This app puts an interactive e-Gemara in your Android, free.

5-Minute Daf Yomi with Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld Rabbi Shmuel Herzfeld of Ohev Sholom - The National Synagogue provides commentary and insight into the daily Daf

Today's Daf – Aleph Society This Daf Yomi series is a unique opportunity to study a page of Talmud each day with one of the world's foremost Jewish scholars.

Mercava. The OS of Jewish education.

Daf Yomi - Kinloss | Finchley United Synagogue Every morning following first Shacharit at 7.40am. Daf Yomi “page of the day” is a daily regimen of learning the Oral Torah and its commentaries

Real Clear Daf » Clear, quick, high-level audio Daf Yomi in honor or in memory of a loved one. © Real Clear Daf | 1-855-ASK-RCD-1 (275-7231) | 123 Pressburg Lane, Lakewood NJ 08701

How Daf Yomi Became Part Of This Working Mom’s Routine The New York Jewish Week

What I've Learned in Five Years of Daf Yomi Daily Talmud Reading … Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

Daf Hachaim Want the Charts & Illustrations While You’re Listening to the Shiur?

You can print out a PDF version of the Illustrations that make the Daf easier to follow! Just go to the “Download Resources” box (on the right hand side of most pages in Daf Hachaim) and click on either of the last 2 choices: “Color PDFs” or “B&W PDFs.” Then just print it out.

It’s a great way to keep the clarity of Daf Hachaim’s Visual Learning while you’re learning inside the Daf itself.

t’s also a handy way to review the Daf while traveling or when you’re otherwise without a computing device.

And it’s indispensible for keeping up with the Daf on Shabbos and Yom Tov!

Advanced Talmud Study - Daf Yomi Gemara Classes - Audio Classes Studying Gemara: Daf Yomi. Listen · Talmud Tractate Rosh HaShanah. Audio. Talmud Tractate Rosh HaShanah. Studying Gemara: Chabad

Jewish Law

& Tradition,

The Talmud,

Shulchan Aruch,

Daf Yomi

|

|