JEWISH NEWS - SPAIN and PORTUGAL500 YEARS AFTER EXPULSION

SPAIN and PORTUGAL

follow Israel

with a Jewish Law of Return

for descendents of Jews whom they had expelled

to correct what they both describe as

‘a moral wrong’SPAIN

Unlike Portugal, Spain Sephardic citizenship plan hits snags

Times of Israel May 15 2015

(from Wikipedia)

There are three categories of Spanish citizenship:

de origen (original citizenship) - [almost exclusively] acquired at the moment of birth, mainly to a Spanish parent, and which can never be lost;

por residencia - acquired through a predetermined period of legal residency in Spain, known as . The distinction is important because Spanish nationality laws primarily follow iure sanguinis, including those relating to the right of return.

por opción (by choice) - given to some people of Spanish origins that, though not complying with the requisites to attain the original citizenship, are able to prove close ties to Spain; this option is given mainly to the children of people that have attained or recovered Spanish citizenship after their birth, but it has age limits and one must exercise this choice prior turning 20 (in some countries, like Argentina, prior turning 23, as majority of age is attained at 21 there). Most of the por opción clauses do not confer original status (except those included in the Historical Memory Law), thus it can be lost, and, in case one possesses nationality other than those described below as historically related to Spain (e.g., United States), renounce their current nationality in front of Spanish consular officials.

In practice this renunciation has little practical effect, and in some cases no effect, as only renunciations made to one's own country's officials has an effect on the linked nationality.

The Historical Memory Law (Spanish: Ley de Memoria Histórica), which took effect in December 2008, introduces temporary (two-year) changes to current Spanish nationality laws. Those whose father or mother were born original Spaniards (regardless of their place of birth, whether they are still living, or whether they currently hold Spanish nationality) and those whose grandparents emigrated due to political or economic reasons will have the right to de origen Spanish nationality. Until and while the Law of Historic Memory takes effect, the following laws will also apply:

1. Spanish-born emigrants (mainly exiles from the Spanish Civil War and economic migrants) and their children are eligible to recover their de origen Spanish nationality without the requirement of residence in Spain. They also have the right to maintain any current nationality they possess.

2. Regardless of their place of birth, the adult children and grandchildren of original Spaniards (original Spaniards are those who, at the moment of their birth, were born to people who possessed Spanish citizenship) can also access Spanish nationality on softer terms than other foreigners: they require just 1 year of legal residence, and they are exempted from work restrictions. This law in practice also benefits the great-grandchildren of emigrant Spaniards as long as their grandparents (born outside of Spain) are/were original Spaniards.

3. Ibero-Americans and citizens of other countries historically related to Spain (Portugal, Andorra, Philippines, and Equatorial Guinea) also have a Right of Return: They can apply to Spanish nationality after 2 years of Legal residence (the usual time is 10 years for most foreigners) and they have the right to keep their birth nationality.

4. Those of Sephardic Jewish origin also have the right to apply for nationality after a year of legal residency in Spain. Upon the rediscovery of Sephardi Jews during the campaigns of General Juan Prim in Northern Africa, the Spanish governments have taken friendly measures towards the descendants of the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 under the Alhambra Decree and persecuted by the Spanish Inquisition. The motivation for these measures was a desire to repair a perceived injustice, the need of a collaborative base of natives in Spanish Morocco, and an attempt to attract the sympathy of wealthy European Sephardis like the Pereiras of France. The Alhambra Decree was revoked.

In November 2012, the Spanish government announced that it would eliminate the residency period for Sephardic Jews, and permit them to maintain dual citizenship, on the condition that such citizenship applicants presented a certificate of their Sephardic status from the Federation of Jewish Communities in Spain.

Spanish diplomacy exercised protection over Sephardis of the Ottoman Empire and the independent Balkanic states succeeding it. The government of Miguel Primo de Rivera decreed in 1924 that every Sephardi could claim Spanish citizenship. This right was used by some refugees during the Second World War, including the Hungarian Jews saved by Ángel Sanz Briz and Giorgio Perlasca. This decree was again put to use to receive some Jews from Sarajevo during the Bosnian War.

In October 2006, the Andalusian Parliament asked the three parliamentary groups that form the majority to support an amendment that would ease the way for morisco descendants to gain Spanish citizenship. The proposal was originally made by IULV-CA, the Andalusian branch of the United Left. Such a measure might have benefited an indeterminate number of people, particularly in Morocco and other Maghreb countries. However, the call went unheeded by the central Spanish authorities (see Morisco#Descendants and Spanish citizenship).

Spain’s justice minister, Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, said that that bill was about addressing a historic aberration and that the expulsion was one of Spain’s, “most important historical errors. Now they [Jewish people] have an open door to become once again what they should have never stopped being — citizens of Spain.”

The Spanish government recently set out the conditions for those applying, which it hopes may limit the numbers. First applicants must prove they are Sephardic Jews — whose ancestors originated in Spain — by way of a certificate from a rabbi, and, more taxingly, prove some link to Spain, including what the opposition Socialists have described as an “integration” test. The government says the requirement includes a knowledge of Spanish or, vaguely, some sort of other connection to Spain.

The move by the Spanish government is not likely to prove universally popular in Israel either, which was established to provide a state for Jews. Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, was criticised in aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris in January when he encouraged French and other European Jews to emigrate to Israel.

“Israel sees the bill as a piece of internal legislation in Spain; as Spain dealing with its dark past in terms of the tragedy of what happened when it kicked out the Jewish people, just because they were Jews,” says Hamutal Rogel Fuchs, a spokesman for the Israeli embassy in Madrid.

“But today, the Jewish people have a home — Israel. So we congratulate Spain for acting, but it is not a question of whether we are comfortable or uncomfortable. Israel sees the bill as a symbolic gesture that reinforces out relationship.”

Avi Mayer of the Jewish Agency in Jerusalem, which encourages Jews to move to Israel, says that he doubts many Sephardic Jews will swap Israel for Spain. “According to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, emigration rates are at an all-time low and have been steadily declining for the past twenty years.

“At the same time, Aliyah [immigration to Israel] is at a 10-year high, and immigration from Western countries has overtaken immigration from the rest of the world for the first time in Israel’s history.”

Rather than flee, large numbers of Jews converted to Catholicism rather than migrate. Last year, Natan Sharansky, the chairman of the Jewish Agency said that Israel must find away to find the descendants of Jews who converted and offer them citizenship of Israel.

Given that Israeli Gross Domestic Product is ahead of that in Spain, it is not likely to that hundreds of thousands of Jews will suddenly appear at Barajas airport in Madrid once the legislation is passed. And, as number of Muslim groups and academics have pointed out, both the Jews and Muslims were victims of Isabella and Ferdinand’s Spanish Inquisition, and so why are only the descendants of the Jewish victims now being offered reparation?

The Guardian (UK) Euronews Jewish Daily Forward

500 YEARS AFTER EXPULSION, JEWISH AMERICAN CLAIMS SPANISH CITIZENSHIP

IN RIGHTING OF HISTORIC WRONG,

SEATTLE-RESIDENT DOREEN ALHADEFF AND OTHER DESCENDANTS

OF SEPHARDIC JEWS RECEIVE OFFICIAL ENTREE TO ANCESTRAL HOMELANDS

UNDER NEW SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE ‘RIGHT OF RETURN’ LAWS

Times of Israel, Janis Siegal, February 23, 2016

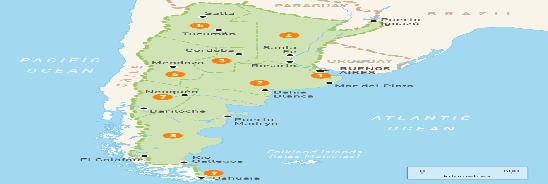

SEATTLE — When Doreen Alhadeff signed her Spanish citizenship papers in Toremmolinos, Spain, a few weeks ago, she became the first Jewish American to officially embrace Spain’s unusual 2015 law. For the first time since Jews were expelled from the country more than 500 years ago, the new legislation, and a similar law in Portugal, allows descendants of Sephardic Jews the option of applying for national rights.After months of gathering documents and going through numerous legal hoops, Alhadeff, a 65-year-old grandmother from Seattle, knew she was making history.“I felt a bit as if I were walking in the footsteps of my grandmother who was the first Sephardic woman to arrive in Seattle,” said Alhadeff after the signing ceremony. “At that moment, I thought of her, and of course, my parents who would have been proud of the achievement.”Alhadeff’s husband, Joseph, who travelled with her, is also planning to apply once he learns Spanish, a skill his wife picked up during her college years studying in Spain in the late ’60s and ’70s.“The language requirement holds me and many others back from taking advantage of this unique and wonderful opportunity,” said Joseph Alhadeff. “I feel very proud of my wife and happy for Sephardics around the world to have this opportunity.”Joseph and Doreen Alhadeff (from left) signing her Spanish citizenship papers on February 2, 2016 in Torremolinos, Spain. (courtesy) Joseph and Doreen Alhadeff (from left) signing her Spanish citizenship papers on February 2, 2016 in Torremolinos, Spain. (courtesy)Today, Doreen Alhadeff is only one of six Americans to complete the citizenship process and earn dual citizenship. She has already opened application files for her grandchildren.“This is becoming a global world,” she said. “With that [Spanish passport], you don’t need a work visa in the entire EU. To me, this is one of the greatest gifts I can give my grandchildren.”‘I felt a bit as if I were walking in the footsteps of my grandmother’Applying for Spanish citizenship is no easy task, however. Once would-be citizens open a digital application file online and upload copies of a passport, a birth certificate and proof of an FBI background check, they need two signed documents, usually from a rabbi or synagogue congregation president, who will vouch for the applicants historic Sephardic connections.They must also pass a basic Spanish language test, along with a Spanish culture and values test.As of January 13, 2016, Spain’s Ministry of Justice reported that 1,016 applicants from many countries have started the process, said Luis Portero, counsel for the Federation of Jewish Communities in Spain, known as the FCJE by its Spanish acronym.Portero, who travelled to the US states of Washington and Oregon to meet with the Sephardic communities, answered questions about the Spanish “right of return” law. He was also one of the people who helped Alhadeff through the application process.Because of the complexity of the process, it took the concerted efforts of the FCJE and the honorary consul of Spain for the Pacific Northwest, Luis Estaban, to make sure all of the legal requirements were met.Estaban is well-acquainted with the Northwest’s Sephardic communities and is the liaison between the Spanish parliament and a majority of the Sephardic population in the two states. According to Estaban, there are about 5,000 Sephardic Jews in Washington and maybe 200 in Oregon.“Generally, there are, maybe, 40 or 50 others who are calling in for more information about Spanish citizenship,” he said.The Spanish government believes that more than two million applicants could potentially apply for citizenship under the new law, but expects to receive between 90,000 and 190,000 applications. The FCJE, however, estimates that between 40,000 and 50,000 Sephardim will apply for a Spanish passport.The number of Sephardim in the Diaspora that could possibly qualify for citizenship under a similar Portuguese law passed in January 2015 is nearly 150,000, the FCJE noted.‘Some of my clients wish to get this citizenship based on sentimental reasons, and some for more practical reasons’To date, there are 16 countries represented in the applicant pool that have started the process online. In the United States, 59 applicants opened online files, according to data from Spain’s Ministry of Justice. Ecuador has the highest number with 167 followed by Argentina with 107. Israel has the third-largest group, with 73 applicants.“This makes it a unique opportunity for the Israelis who never thought they could obtain a European citizenship because their parents or grandparents were not born in Europe,” said attorney Maya Weiss-Tamir, the founder of a law firm that is helping its clients with Spanish citizenship applications in Israel.“I can say that some of my clients wish to get this citizenship based on sentimental reasons, and some for more practical reasons,” said Weiss-Tamir.According to Alhadeff, while in Madrid, a Jewish man from Colombia who was also there to sign citizenship papers remarked that a Spanish passport gives every Jew another place to go “just in case” and also felt it was important for his children and grandchildren.Once the Spanish government has given its written approval for granting citizenship, an applicant has one year within which to return to Spain and formally apply for the passport.“I think citizenship is very important and that it’s a gift forever,” said Alhadeff. “It’s generational, and the descendency goes on forever.”PORTUGALDESCENDANTS OF SEPHARDIC JEWS PORTUGALACQUISITION OF PORTUGUESE CITIZENSHIP

BY THE DESCENDANTS OF SEPHARDIC JEWS PORTUGAL.

CLICK HERE FOR THE CONDITIONS.New citizenship law has Jews worldwide

flocking to tiny Portugal city

Jewish Telegraphic Agency By Cnaan LiphshizFebruary 11, 2016 3:56pm

PORTO, Portugal (JTA) — Five years ago, this city’s tiny Jewish community was so strapped for cash it couldn’t afford to fix the deep cracks in its synagogue’s moldy ceiling.

The Jewish Community of Porto was also too poor to hire a full-time rabbi because of its small size (50 members) and the paucity of donors in a country gripped by a financial crisis.But last month the community, situation 200 miles north of Lisbon, showcased its stunning turnaround. Hosting the biggest event in its history, it drew hundreds of guests from all over the world to the city’s newly opened kosher hotel and newly renovated synagogue. The community also has a new Jewish museum and mikvah ritual bath, and there are plans to build a kosher shop, Jewish kindergarten and school.The money, community members say, came from a massive influx of Jewish tourists that coincided with the implementation of Portugal’s 2013 law of return for Sephardic Jews and their descendants.The law named the Porto community, founded by a handful of converts to Judaism, one of two institutions responsible for vetting citizenship applications, providing the Jews in this little-known city of 230,000 with tens of thousands of dollars in income and turning Porto into a destination for Jews from around the world.“This law not only gave us new funds but put us on the world map,” said Emmanuel Fonseca, a 53-year-old Orthodox convert to Judaism. “In no time, we went from a tiny group struggling to exist to a well-to-do congregation with local and international standing. I never thought I would live to see this.”Applying for membership in Lisbon and Porto’s official Jewish community costs $300-$560 and is a required step for a Jew to become a Portuguese citizen under the 2013 law. (Spain recently passed a similar law aimed at descendants of Sephardic Jews.) Each application must be checked by one of the two Jewish communities against their records and lists of lineages. Some of the hundreds of applicants to Porto have added handsome donations on top of the required fee.So far, only three of the hundreds of citizenship applications have been approved, a wrinkle that Leon Amiras, an Israeli attorney handling citizenship requests and chairman of the Association of Olim from Latin America, Spain and Portugal, attributed to bureaucratic complications connected to last November’s elections in Portugal. Amiras said he expects hundreds of applications to be approved this year.Meanwhile, Porto is becoming a more attractive prospective home for Jews with European Union passports, who can move here without obtaining citizenship. Yoel Zekri, a French Jewish student in his 20s who temporarily moved here last year from Marseille, where five Jews have been assaulted in three stabbing attacks since October, said he’s considering staying on after his studies “to help build the community.”“I no longer feel comfortable in France,” Zekri said. “I would never wear a kippah on the street. Here people sometimes tell me they are happy to see the Jews return.”Congregants praying at the Kadoorie - Mekor Haim synagogue in Porto, Portugal, May 2014. (Courtesy of the Jewish Community of Porto)Congregants praying at the Kadoorie – Mekor Haim synagogue in Porto, Portugal, May 2014. (Courtesy of the Jewish Community of Porto)Porto hasn’t seen a single anti-Semitic incident over the last decade, according to the mayor, Rui Moreira, who spoke last month at an event at the synagogue and obliquely referenced the rising anti-Semitic violence elsewhere in Europe.“This synagogue was built when others across Europe were being burned,” he said. “Today it again offers shelter from the bad winds blowing around us.”Alexandre Sznajder, a Jewish businessman from Rio de Janeiro with a Polish passport who was in town for the kosher hotel and synagogue celebration, is thinking about moving to Porto with his wife and son.“The economic situation in Brazil is deteriorating and personal security is terrible,” said Sznajder, an importer who said he was kidnapped for ransom two years ago. “If I can keep doing business from here, where it’s safe, Porto could be the place for us.”Some applicants for Portuguese citizenship from non-EU countries want a Portuguese passport as an insurance policy, in the event things in their home countries go south. Hila Loya, a visitor from Cape Town, applied last year for that reason.In South Africa, she said, “the anti-Israel, anti-Jewish atmosphere is worsening, and there’s a feeling things mAY turn for the worse in the near future.”READ: In Portugal, Jewish law of return moves from Facebook to law bookLast month, approximately 250 Jews from 14 countries convened here for a weekend retreat designed to introduce them to Porto and its Jews. Among those present were the president of Lisbon’s Jewish community, Turkish Chief Rabbi Ishak Haleva and 80 other Turkish Jews. Most of the applicants to Porto’s community so far have been Turkish Jews, including many of those who came for the weekend retreat.Haleva, one of Sephardic Jewry’s most respected religious figures, said he came not to apply for citizenship – “I’m a Turkish Jew, period” – but to visit “this place where our roots are.” Many of Turkey’s Jews are descended from Sephardic Jews who fled northern Portugal after 1536, when Portugal joined Spain in applying the Inquisition’s expulsion orders against Jews, according to Haleva. And many of those who fled from Portugal to Turkey originally came from Spain, where the Inquisition began in 1492.Turkish Chief Rabbi Ishak Haleva, right, talking to congregants outside Kadoorie - Mekor Haim synagogue in Porto, Portugal, Jan. 29, 2016 (Cnaan Liphshiz) Congregants carrying a Torah scroll into the Kadoorie – Mekor Haim synagogue in Porto, Portugal, Jan. 29, 2016 (Cnaan Liphshiz)Tens of thousands of Jews stayed in Portugal and converted to Christianity. While many continued to practice Judaism in secret as anusim – Hebrew for “forced ones” — the Jewish presence ultimately vanished from this once heavily Jewish area. The Jewish revival was sparked in 1923, when a Portuguese army captain, Arthur Carlos Barros Basto, reached out to the descendants of the anusim, leading to the construction of Porto’s synagogue.Built in 1939, the community’s Kadoorie – Mekor Haim synagogue is among the largest and most beautiful in the Iberian Peninsula, but it saw long periods of neglect until last year’s extensive renovations were completed. That helped put a new shine on the synagogue’s best features: Moroccan-style interior arches; heavy redwood interior and dazzling collection of more than 20,000 hand-painted azulejos, Portugal’s iconic ceramic tiles.When Porto’s mayor dropped in at last month’s retreat, it was his second time at the city’s shul – a sign of the Jewish community’s increased significance in Porto, according to the local rabbi, Daniel Litvak.Addressing 300 guests from the synagogue’s podium while wearing a kippah, Moreira, who himself is descended from an Ashkenazi Jew who settled in Porto in the 19th century, said Portugal’s new law of return was to “correct a historical wrong” — the 16th-century expulsion of Portugal’s Jews.But, he added, “the law has future implications: We want you to come live here, with us, and share that future.”PORTUGUESE CITIZENSHIPUp to July 2016, the Portuguese government has granted more than 800 nationalities to Sephardic Jews. The majority of these applicants obtained previously their certificates issued by the Jewish Community of Oporto. The Portuguese citizenship was granted to applicants whose families were integrated into communities known as "Sephardim": Turkey, Greece, old Palestinian, former Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Syria, Lebanon, Macedonia, Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, etc..Recently, after Brexit vote, British Jews seek Portuguese citizenship

(the Express Tribune) and (TheJewishChronicle)JEWISH LAW OF RETURN

WikiAn amendment to Portugal’s 'Law on Nationality' allows descendants of Jews who were expelled in the Portuguese Inquisition to become citizens if they ' belong to a Sephardic community of Portuguese origin with ties to Portugal.'The Portuguese parliament passed legislation facilitating the naturalization of descendants of 16th-century Jews who fled because of religious persecution. On that day Portugal became the only country besides Israel enforcing a Jewish Law of Return. Soon after, Spain adopted a similar measure.The motion, which was submitted by the Socialist and Center Right parties, was read on Thursday 11 April 2013 in parliament and approved unanimously on Friday 12 April 2013 as an amendment to Portugal’s "Law on Nationality."It allows descendants of Jews who were expelled in the 16th century to become citizens if they "belong to a Sephardic community of Portuguese origin with ties to Portugal," according to Jose Oulman Carp, president of Lisbon's Jewish community. According to the website of the World Jewish Congress, the Jewish Community of Lisbon is the organization that unites local communal groups of Lisbon and its environs, while the Jewish Community of Oporto is the organization that unites local communal groups of Oporto.Applicants must be able to show "Sephardic names." Another factor is ‘the language spoken at home’, a reference which also applies to Ladino. The amendment also says applicants need not reside in Portugal, an exception to the requirement of six years of consecutive residency in Portugal for any applicant for citizenship.

PORTUGAL APPROVES CITIZENSHIP PLAN FOR SEPHARDIC JEWS

LISBON, Portugal — Jan 29, 2015, 11:54 AM ET

By BARRY HATTON Associated Press

_____________________

Like Dreyfus, Captain Barros Basto was cleared of all charges on February 29, 2012 by the National Assembly of Portugal which voted unanimously upon the recommendation of Carlos Abreu Amorim and Fernando Negrão, members of the Civil Rights Committee of the National Assembly who found the accusations of 1937 (and confirmed in 1975) against the Captain to be baseless and motivated by anti-semitism. The Captain's posthumous reinstatement into the Army is imminent.The Captain's granddaughter, Isabel Ferreira Lopes, who like her grandmother and mother have campaigned relentlessly for the rehabilitation of her grandfather, called the 1937 decision immoral, not her grandfather. She gratefully acknowledged the courage of the Civil Rights committee and the National Assembly in righting an historic wrong. She called it a victory for her grandfather, a victory for Portuguese Marranos, a victory for all Portuguese people,and a victory for all people fighting injustice. Abraham H. Foxman, the National Director of the Anti-Defamation League congratulated Portugal's National Assembly and said, “The vote was not only in favor of reinstating him, but was also in favor of Portugal’s honor. Just as this act of discrimination reflected a larger societal problem at the time, the long overdue rehabilitation of Captain Barros Basto reflects Portugal’s commitment to human rights today.”

|

PORTUGAL HAS ONLY APPROVED 8% OF SEPHARDIC JEWISH APPLICATIONS FOR CITIZENSHIP SINCE MARCH 2015,

when descendants of Jews persecuted 500 years were granted the right to apply for citizenship, 3,546 applications remain in pending, and a mere 292 have been approved.

YNet News J. S. Herzog, 24.10.16

Portugal's Institute of Registers and Notaries (IRN) has so far only approved a mere 8%—292 out of 3,838—of the applications for Portuguese citizenship from the descendants of Sephardic Jews who were persecuted under the Inquisition, Público newspaper reported.

Portugal approved a law in March of 2015 that grants citizenship rights to the descendants of Jews it persecuted 500 years ago. The rights apply to those who can demonstrate "a traditional connection" to Portuguese Sephardic Jews, such as through "family names, family language, and direct or collateral ancestry."

Público reported that of the 3,546 unapproved applications, none have yet been denied. They remain in treatment.

The Ministry of Justice, to which the IRN belongs, was quoted in the Lisbon-based daily as stating that the complex process requires "a rigorous examination of the submitted documents" along with the verification of the submitted data with public bodies, such as the ministry's own Judicial Police, the Ministry of Internal Affairs' Foreigners and Borders Service and the Directorate-General of Justice Administration.

Applicants also must be vetted by Portuguese Jewish community institutions in Lisbon or Porto, who are responsible for checking existing documentation of the applicants' ancestors, often written in Ladino.

A plurality of applications have thus far come from Turkey (about 50%), and Israel (31%) and Brazil follow, Público wrote. When the law first came into effect, the IRN had a monthly average of about 46 applications which this year grew to 374, the Ministry of Justice relayed.

After Spain drove out Jews in 1492, some 80,000 of them crossed the border into Portugal, historians estimate. King Joao II charged the fleeing Sephardic Jews a tax to shelter in Portugal. He promised to provide them with ships so they could go to other countries, but later changed his mind.

In 1496 his successor King Manuel I, eager to find favor with Spain's powerful Catholic rulers, Ferdinand and Isabella and marry their daughter Isabella of Aragon, gave the Jews 10 months to convert or leave. When they opted to leave, Manuel issued a new decree prohibiting their departure and forcing them to embrace Roman Catholicism as "New Christians."

The "New Christians" adopted new names, inter-married and even ate pork in public to prove their devotion to Catholicism.

Some Jews, though, kept their traditions alive, secretly observing the sabbath at home then going to church on Sunday. They circumcised their sons and quietly observed Yom Kippur, calling it in Portuguese the "dia puro," or pure day. Though officially accepted, the New Christians were at the mercy of popular prejudice. In the Easter massacre of Jewish converts in 1506 in Lisbon, more than 2,000 Jews are believed to have been murdered by local people.

The Portuguese Inquisition, established in 1536, was at times crueler than its earlier Spanish counterpart. It persecuted, tortured and burned at the stake tens of thousands of Jews. Now those events are widely viewed as a stain on Portuguese history. |