|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

Syria boasts one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities and one of the world’s richest and most storied Jewish cultures. Its history dates back to Biblical times, and its Jews have survived the many empires that conquered it. Its once thriving community has been reduced to about 50 who face rampant civil war, repressive government measures, and limited economic opportunities.

The civil war that started in 2011 (now 2020) has seen much of the country in ruins, hundreds of thousands dead or wounded, millions leaving as refugees and a shattered economy. The hope is that when it stops and rebuilding starts that most refugees will return and the country will be rebuilt and be prosperous.

Adam Entous, Wall Street Journal Dec. 1, 2014,

Syria used to be home to a vibrant Jewish community. The few that remain holed up in Damascus are wary bystanders to the country’s civil war, as reported by The Wall Street Journal.

The number of Jews in Syria peaked in the early 20th century. At the time, an estimated 25,000 Jews lived in the country, split roughly evenly between Damascus and Aleppo, according to Abraham Marcus, an expert on Middle Eastern history and the Jewish community of Syria at the University of Texas at Austin.

At first, Syrian Jews started leaving for economic reasons.

The Jewish exodus surged in the run-up to the founding of the state of Israel in 1948. In 1947 and 1948, about 7,000 of the 12,000 remaining Jews left their homes and moved to the new Jewish state and to other countries, according to Mr. Marcus.

The Syrian government soon imposed a ban on Jewish emigration that lasted for 45 years, Mr. Marcus said. Many Jews defied the travel restrictions and managed to slip across the border into Turkey or Lebanon.

A secret campaign by a Jewish musicologist in Toronto named Judy Feld Carr helped more than 3,200 Jews leave Syria starting in 1977. Many emigrated to the U.S. and Israel.

In 1992, the late Syrian President Hafez al-Assad opened the door for the remaining Jews in Syria to emigrate.

By 2008, when Mr. Marcus visited Syria to research a book on the Jewish community there, the number of Jews had shrunk to between 60 and 70 in Damascus. Another six Jews remained in Aleppo, he said.“You could say it was a community on the way to extinction,” he said. “The internal war in Syria has just expedited that process.”

Around 17 Jews remain in Damascus today, according to community leaders.

TIMELINE

jimena

1000 BCE It is alleged, that King David’s general, Joab, occupied the site of Aram Zoba, or Aleppo.

64 BCE Syria is annexed by the Roman Empire and Jews in the region begin to suffer.

66-73 CE Syrian forces are directly engaged in the Great Jewish Revolt and were ordered to quell the uprisings in Judea.

614 Syria is conquered by the Persians, ending the oppression Jews experienced under the Roman and Byzantine Empire.

635 Damascus fell into the hands of the Umayyad Muslims during the Arab Conquest and life began to improve.

8th – 10th Century During the Abbasid Dynasty, the Central Synagogue of Aleppo is built and the city becomes a center of Jewish scholarship and spirituality.

1148 Damascus resists the Second Crusade and in the following years many Jewish refugees from Jerusalem find refuge in Damascus.

1375 A descendent of Maimonides brings the Aleppo Codex from Egypt to Aleppo, where it would remain protected for 600 years.

1492 Jewish refugees from Spain are welcomed by Syria’s indigenous, flourishing Jewish community.

1516 Damascus falls to the Turks, becoming part of the Ottoman Empire. Jews are considered dhimmis.

1840 Eight members of the Jewish community were falsely accused of ritual murder of a Christian monk during the Damascus Affair. The men were tortured, killed, and forced to convert to Islam. The Jewish synagogue of Jobar is destroyed.

1850 As blood libels against Jews increase and Aleppo begins to experience economic decline, Jewish waves of emigration to North American, North Africa, and Europe begin.

1947 After the Partition Plan rioters took to the streets of Aleppo leaving 75 dead and destroying Jewish community sites, Jewish homes and businesses, and sacred artifacts and manuscripts including the Aleppo Codex.

1948-1992 The 30,000 Jews left in Syria experience extreme economic strangulation, with Jewish bank accounts frozen and Jewish members of government discharged. Jews are subjected to severe restriction of freedom of movement and are not allowed to acquire a drivers license or leave the country freely. Jews were under constant surveillance by the secret police. Syrian Jews who want to leave are forced to escape and those who were caught faced execution or forced labor.

1949 The Menarsha synagogue in Damascus suffered a grenade attack, killing 12 people and injuring dozens.

1974 Four Jewish girls were raped, murdered, and mutilated after attempting to flee to Israel. Their bodies were discovered with the remains of two Jewish boys who had previously tried to escape.

1989 The Syrian government agreed to facilitate the emigration of 500 single Jewish women.

1991 Following heavy lobbying from Jewish Syrian Americans, during the Madrid Peace Conference, the USA pressured Syria to ease restriction on its Jewish population.

1992 4,000 Jews in Damascus, Aleppo, and Qamishli were granted exit permits. Some 300, mostly elderly Jews remained after the rest fled.

2012 Only twenty elderly Jews remain in Syria.

JEWISH HISTORY

Wikipedia

Syrian Jews (Hebrew: יהודי סוריה Yehudei Suriya, Arabic: اليهود السوريون Al-Yehud al-Suriyyun, colloquially called SYs /ˈɛswaɪz/ in the United States) are Jews who lived in the region of the modern state of Syria, and their descendants born outside Syria. Syrian Jews derive their origin from two groups: from the Jews who inhabited the region of today's Syria from ancient times (known as Musta'arabi Jews, and sometimes classified as Mizrahi Jews, a generic term for the Jews with an extended history in the Middle East or North Africa); and from the Sephardi Jews (referring to Jews with an extended history in the Iberian Peninsula, i.e. Spain and Portugal) who fled to Syria after the Alhambra Decree forced the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 CE.

There were large communities in Aleppo (the Halabi Jews, Aleppo is Halab in Arabic) and Damascus (the Shami Jews) for centuries, and a smaller community in Qamishli on the Turkish border near Nusaybin. In the first half of the 20th century a large percentage of Syrian Jews immigrated to the U.S., Latin America and Israel. Most of the remaining Jews left in the 28 years following 1973, due in part to the efforts of Judy Feld Carr, who claims to have helped some 3,228 Jews emigrate; emigration was officially allowed in 1992.The largest Syrian Jewish community is located in Brooklyn, New York and is estimated at 75,000 strong. There are smaller communities elsewhere in the United States and in Latin America.

In 2011 there were about 50 Jews still living within Syria, mostly in Damascus.

As of May 2012, only 22 Jews were left in Syria. This number was reported to be down to 18 in November 2015.

From Aish

Syria boasts one of the world’s oldest Jewish communities and one of the world’s richest and most storied Jewish cultures. Syria has a history that dates back to Biblical times, and its Jews have survived the countless empires that have conquered it. That once thriving community has been reduced to some 50 members that face rampant civil war, repressive government measures, and limited economic opportunities.

A MILLENNIA-OLD PAST

Syrian Jewry’s illustrious past began thousands of years ago during the time of Ezra the Scribe, who was tasked with appointing judges in Syria by the Persian king Xerxes. Jews gained significant privileges under the Greeks and Romans, and sent lavish offerings to the Second Temple in Jerusalem. The Jewish sages held Syria and its Jewish population in such high regard that they applied the same land laws to Syria as to Israel: as it says in the Mishnah, “He who buys land in Syria is as one who buys in the outskirts of Jerusalem” (Hallah, 4:11).

The main center in ancient Jewish Syria was Damascus, now the capital of the Syrian Arab Republic and quite possibly the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. Damascus is referenced in the Hebrew Bible, as well as the Talmud and Dead Sea Scrolls, as Dammesek. King David campaigned against the Arameans there, and the city was later conquered by the Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans. As in the rest of Syria, Jews fared particularly well. Damascus became a major economic hub in the Levant. According to the sage Resh Lakish, the city could be one of the “gateways of the Garden of Eden” (Er. 19a).

As the Roman Empire transformed into the Christian Byzantine Empire, it found itself constantly at war with the Persians over the possession of Syria. Eventually, Persia conquered Syria and Israel with the help of Jewish supporters who had resented the exorbitant privileges Christians enjoyed under Byzantine rule.

In 635, Syria fell under the control of the Arabs, who had recently united under the banner of Islam. The Muslim Umayyad empire chose Damascus as its capital and the city prospered once again. Many Jews held high positions during the early years of the Muslim empire including Manasseh ibn Ibrahim al-Qazzāz who was in charge of finances during the Shi’ite Fatimid era of the late 10th century C.E. Damascus became a center of Talmudic study, establishing an academy that had close ties with its counterparts in the land of Israel.

SYRIAN-ISRAELI RELATIONS

Wikipedia

Israel–Syria relations refers to bilateral ties between Israel and Syria. The two countries have since the establishment of the State of Israel been in a state of war. The countries have fought three major wars, which are the 1948 Arab Israeli War in 1948, the Six-Day War in 1967, and the Yom Kippur War in 1973, later also being involved in the Lebanese Civil War and the 1982 Lebanon War, as well as the War of Attrition. At other times armistice arrangements have been in place. Efforts have been made from time to time to achieve peace between the neighbouring states, without success.

Syria has never recognised the State of Israel and does not accept Israeli passports for entry into Syria. Israel also has regarded Syria as an enemy state and generally prohibits its citizens from going there. There have not been diplomatic relations between the two countries since the creation of both countries in the mid-20th century.

There have been virtually no economic or cultural ties between the two countries, and a limited movement of people across the border. Syria continues to be an active participant in the Arab boycott of Israel. Both countries do allow a limited trade of apples for the Golan Druze villages, located on both sides of the ceasefire line, and Syria supplies 10% of the water for the town of Majdal Shams, near the Syrian border, as a part of an agreement that has been ongoing since the 1980s.[1] The state of peace at the ceasefire line has been strained during the Syrian civil war, which began in 2011 and is ongoing.

DURING SYRIAN CIVIL WAR: 2011–PRESENT

Main article: Israeli–Syrian ceasefire line incidents during the Syrian Civil War

Main article: Israeli involvement in the Syrian Civil War

Several incidents have taken place on the Israeli–Syrian ceasefire line during the Syrian Civil War, straining the state of peace between the countries. The incidents are considered a spillover of the Quneitra Governorate clashes since 2012 and later incidents between the Syrian Army and the rebels, ongoing on the Syrian-controlled side of the Golan and the Golan Neutral Zone and the Hezbollah involvement in the Syrian Civil War. Through the incidents, which began in late 2012, as of mid-2014, one Israeli civilian was killed and at least 4 soldiers wounded; on the Syrian-controlled side, it is estimated that at least ten soldiers were killed, as well as two unidentified militants, who attempted to penetrate into Israeli-occupied side of the Golan Heights.[8]

On 11 May 2018, Israel urged Syria to reduce the level of Iranian military presence in the country, with Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman stating: "Throw the Iranians, Qassem Soleimani and the Quds forces out of your country! They are not acting in your interest, they are only hurting you. Their whole presence only brings problems and destruction."[9]

On 10 July 2018, Lieberman did not rule out establishing "some kind of relationship" with Syria under Assad.[10]

On 11 July 2018, Netanyahu stated that Israel was not seeking to take action against Assad, but urged Russia to facilitate the withdrawal of Iranian troops from Syria.[11]

On 2 August 2018, Lieberman stated his belief that Syrian troops regaining control of the country's border with Israel would reduce the chance of conflict in the Golan Heights by providing "a real address, someone responsible, and central rule".[12]

ECONOMIC RELATIONS

There have been virtually no economic relations between the two countries since the creation of the state of Israel, and a limited movement of people across the border. Syria continues to be an active participant in the Arab boycott of Israel.

As an exception, since 2004 Syria has accepted apples from Israel through the Quneitra crossing. In 2010, Syria accepted some 10,000 tons of apples grown by Druze farmers in the Golan Heights.[13] Israeli minister Ayoub Kara called for an agreement with Syria over the supply of water to towns in the Golan Heights. Today, 10% of water in the Druze town of Majdal Shams is supplied by Syria, from the Ein al-Toufah spring. This arrangement has been in place for 25 years.[14]

WHY ARE ISRAEL AND IRAN FIGHTING IN SYRIA,

IN 300 WORDS

Israel has bombed Iranian targets inside Syria

- leading to fears confrontations

between the two powerful arch-foes could get worse.

Here's the background to what is happening.

BBC 10 May 2018

WHY ARE ISRAEL AND IRAN ENEMIES?

Ever since the Iranian revolution in 1979, when religious hardliners came to power, Iran's leaders have called for Israel's elimination. Iran rejects Israel's right to exist, considering it an illegitimate occupier of Muslim land.

Israel sees Iran as a threat to its existence and has always said Iran must not get a nuclear weapon. Its leaders are worried by Iran's expansion in the Middle East.

WHAT HAS SYRIA GOT TO DO WITH IT?

Israel has watched anxiously as its neighbour Syria has been consumed by war since 2011.

WHY IS THERE A WAR IN SYRIA?

Israel has stayed out of the fighting between the Syrian government and rebels.

The Israeli military defends the occupied Golan Heights, on the boundary with Syria

But Iran has played a bigger and bigger role backing Syria's government by sending thousands of fighters and military advisers.

Israel is also worried that Iran is trying to secretly send weapons to fighters in Lebanon - Israel's neighbour - who also threaten Israel.

Israel's prime minister has repeatedly said that his country would not let Iran create bases in Syria which could be used against Israel.

So as Iran has become stronger in Syria, Israel has intensified its strikes on Iranian targets there.

HAVE IRAN AND ISRAEL EVER ACTUALLY BEEN AT WAR?

No. Iran has long backed groups which target Israel - such as Hezbollah and the Palestinian militant organisation Hamas.

But a direct war would be massively destructive for both sides.

Iran has an arsenal of long-range missiles and heavily armed allies on Israel's borders.

Israel has a very strong army and is said to have nuclear weapons. It is also solidly backed by the United States.

GOLAN HEIGHTS

BBC, 25 March 2019

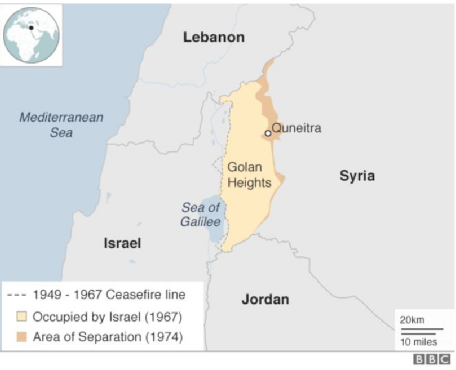

The Golan Heights, a rocky plateau in south-western Syria, has a political and strategic significance which belies its size.

Israel seized the Golan Heights from Syria in the closing stages of the 1967 Six-Day War. Most of the Syrian Arab inhabitants fled the area during the conflict.

An armistice line was established and the region came under Israeli military control. Almost immediately Israel began to settle the Golan.

Syria tried to retake the Golan Heights during the 1973 Middle East war. Despite inflicting heavy losses on Israeli forces, the surprise assault was thwarted. Both countries signed an armistice in 1974 and a UN observer force has been in place on the ceasefire line since 1974.

Israel unilaterally annexed the Golan Heights in 1981. The move was not recognised internationally, although the US Trump Administration did so unilaterally in March 2019.

There are more than 30 Jewish settlements on the heights, with an estimated 20,000 settlers. There are some 20,000 Syrians in the area, most of them members of the Druze sect.

STRATEGIC IMPORTANCE

While still under Syrian control, the Golan Heights were used to bombard Israeli territory below

Southern Syria and the capital Damascus, about 60 km (40 miles) north, are clearly visible from the top of the Heights while Syrian artillery regularly shelled the whole of northern Israel from 1948 to 1967 when Syria controlled the Heights.

The heights give Israel an excellent vantage point for monitoring Syrian movements. The topography provides a natural buffer against any military thrust from Syria.

The area is also a key source of water for an arid region. Rainwater from the Golan's catchment feeds into the Jordan River.

The land is fertile, and the volcanic soil is used to cultivate vineyards and orchards and raise cattle. The Golan is also home to Israel's only ski resort.

STUMBLING BLOCKS

Syria wants to secure the return of the Golan Heights as part of any peace deal. In late 2003, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad said he was ready to revive peace talks with Israel.

In Israel, the principle of returning the territory in return for peace is already established. During US-brokered peace talks in 1999-2000, then Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak had offered to return most of the Golan to Syria.

But the main sticking point during the 1999 talks is also likely to bedevil any future discussions. Syria wants a full Israeli withdrawal to the pre-1967 border. This would give Damascus control of the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee - Israel's main source of fresh water.

Israel wishes to retain control of Galilee and says the border is located a few hundred metres to the east of the shore.

A deal with Syria would also involve the dismantling of Jewish settlements in the territory.

Public opinion in Israel has generally not favoured withdrawal, saying the Heights are too strategically important to be returned.

ON-OFF TALKS

Indirect talks between Israel and Syria resumed in 2008, through Turkish government intermediaries, but were suspended following the resignation of Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert over a corruption inquiry.

The Israeli government under Binyamin Netanyahu elected in February 2009 indicated that it was determined to take a tougher line over the Golan, and in June 2009 Syria said there was no partner for talks on the Israeli side.

SYRIAN CIVIL WAR

The US administration of President Barack Obama declared the restarting of talks between Israel and Syria to be one of its main foreign policy goals, but the advent of civil war in Syria in 2011 put paid to any progress.

Syrian fighting reached the Golan ceasefire lines in 2013, but the resurgent Syrian government felt confident enough to reopen its Golan border crossing to UN observers in October 2018.

See Also Golan Heights Encyclopedia Britannica

ISRAELI HOSPITALS

PROVIDE CARE TO THOUSANDS OF SYRIANS

Globes, Dror Feuer, 26 Mar, 2018

200,000 Syrians near the border look to Israel for help. Children get top priority, and not only the wounded. "Globes" visits the Golan and travels with patients to Galilee hospitals.

Azzam is in the Ziv Medical Center in Safed. When he was three years old and walked out of a mosque in his home village near Quneitra, a rocket exploded and blinded him in both eyes. It was just after the Syrian civil war began, and he has been blind ever since. "There are a lot of airplanes and explosions, and I'm in darkness all the time," he says. "I'm always scared." Azzam is 10 years old now, and this is the sixth time that he has come to Israel for treatment. Seven year-old Ruba, who was born in the village of Shams, suffers from a chronic disease. It is her first visit to Israel. "I'm not scared of the airplanes," she says, "but I am scared of the explosions. It's the scariest thing in the world. And I'm scared of the dark."

12 year-old Islam arrived in Israel today for the first time for medical treatment. "The scenery here is beautiful," she says. I ask what children do in the war, whether there is school, and where they play in the afternoon. They say that sometimes there is school, but most of the time not. There are no air-conditioners, computers, gymnasiums, or laboratories in the schools. It's frightening to play outside in the afternoon - some children go outside and never come back - so they stay home. None of them has ever been to a movie theater, play, or amusement park. They have almost never been out of their village. "We have nothing," says Azzam, "We're Syrians."

A few hours earlier, 4:30 AM on the Golan Heights, just before sunrise. The sky is full of stars, and the air is so crisp and tasty that I don't breathe it; I take bites of it. The many-sided civil war in Syria is about to enter its eighth year, with no end in sight. Every week is worse than the one before, with half a million dead and 12 million homeless and refugees, over a quarter of them children, to date. No one even bothers counting the wounded anymore, but about 5,000 of them have been treated in Israel in the past five years. I attended one of the days of treatment.

Israel never wanted to intervene, but after two years of warfare, the wounded just started coming to the border. Some of them were treated on the spot. At some point, a field hospital was set up and then closed down, with the wounded being sent to hospitals in northern Israel. Over the years, a change occurred in the kind of wounded who came. At first, first aid was given to people wounded in the fighting, but time, the collapse of the Syrian health system, and the changes in the state of the fighting and control over southern Syria have made Israel and its three northern-most hospitals - the Galilee Medical Center in Nahariya, the Ziv Medical Center in Safed, and the Poriya Medical Center in Tiberias - responsible, or at least accessible, for medical treatment for 200,000 Syrians living on the other side of the border in a 40-kilometer strip of land between Quneitra and the triple border, who are completely cut off from Damascus. The IDF calls these Syrians "the locals."

"WE'RE ALL GETTING SADDER"

I attach myself to a force of paratroopers somewhere on the Golan Heights. Major Dr. Sergey Kotikov, head of the medical section, is commanding the operation today. Mauda is the commander of the force. We stand around for a short briefing and start walking in formation towards the Syrian border, between mine fields. Every so often, we stop for a minute or crouch down behind a boulder, talk on the radio, move from here to there, and take up a better position. I am wearing a flak jacket and a helmet, and to tell the truth, am enjoying myself. I know that it is not funny, that not far from here, there is a war, Iranians, and Hezbollah, but I can't help myself. Jackals howl at the rapidly disappearing moon. The skies are clearing up, and the sun is rising over this quarrelsome land. Everything here will soon be yellow and dried up, but for the next week or two, the Golan Heights will be green and stunning, and certainly now, when it is covered by the morning mist.

We are waiting right next to the border. The noise of a motor on the other side comes near. The Syrians come in pairs, mother and child, about 40 people. They come one by one to a small gate in the fence, and follow the instructions: turn around, bend down, undergo a check, and wait. It takes about 40 embarrassing minutes. They stand in the improvised checking area and look at each other. We are on one side, and they are on the other. They all cough loudly. Some of the mothers here are children themselves; they look 15 years old. There are several really small babies. Everyone is quiet and terrified. The children are more silent than any more fortunate Israeli child has ever been.

A report published two weeks ago by the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) states that 2017 was the worst year for Syrian children, with over 5,000 killed. Over 1,000 children were injured in just the first two months of the year. UNICEF Middle East and North Africa regional office director Geert Cappelaere writes, "There are scars on children that will never be erased. The protection of children in all circumstances that was once universally embraced - at no moment has any of the parties accepted.”

After all of them have been checked, they go back to the bus and travel to a secured section of the Ziv Medical Center that has been evacuated for us. Breakfast is served to the stunned Syrians, and they eat it quietly. A man in his forties enters the section. He enters a room with a large bag and closes the door behind him. A few minutes later, medical clown Kukuriku emerges from the room. Red nose, striped pants, large shoes, all the trimmings.

At first, I admit, I was a little dismissive, but I watched while this clown, Johnny Havis, 44, worked miracles in the room. I watch while, with infinite patience, he gets them on their feet, induces them to applaud, or just wave, with gentleness and determination extracts a smile from those children, and doesn't stop until they are all laughing and dancing. Children just want to laugh and play. Before our eyes, he simply mines the joy out of the depths of the souls of these children, who never harmed anyone; they were simply born in the wrong place at the worst possible time.

This is truly one of the most impressive human things I have ever seen. It was a little harder with the mothers, whose eyes showed infinite suffering. These women have seen too much, but Havis did everything possible. Later, when he took a time out, I approached him. He has been working with the Syrian children for five years, and appears in almost every story about the subject. "It will only get worse as the war continues," he says. "We're all getting sadder."

"IT'S OUR DUTY AND PRIVILEGE TO HELP"

I go around with the children - up and down from the cardiology department to ear, nose and throat, orthopedics, and ophthalmology. A soldier stands on guard outside every door behind which a child is being examined. I call Lieutenant Colonel A, the commander, who tells me about another clinic that has been operated by a US organization on the other side of the border under Israeli protection since last August in which 4,000 more patients have been treated. A says that 90% of the humanitarian activity comes from donations. NIS 270 million has been raised to date, mostly for medical equipment and medicine.

A explains, "No treaty is being signed here, but bridges are being built, one by one with the medicine, doctors' visits, and equipment being transferred, in the hope that it will make them trust us. The more we help, the more effective it will be in keeping terrorism away from the border. It's our duty and our privilege to help."

"I'll tell you about the first lesson I learned," says Dr. Michael Harari, a pediatrician at Ziv Medical Center. "I used to work in intensive care, but I've never seen such frequent and severe war wounds. I remember that at the beginning a mother and her daughter came when they were both wounded. The child wouldn't come out from under the blanket, and wouldn't eat or drink anything. We learned something from her about how to overcome post trauma: first of all, put the mother and the girl together. The girl preferred seeing her mother wounded to imagining the worse of all. First of all, unite the families. And the most import thing is to reduce pain. You can't overcome mental trauma if you have a physical trauma. Get rid of the pain, even if it means anesthetizing the child in order to change bandages.

"The second most important thing I learned is about the meaning of home. Even if your home has been bombarded, even if it no longer exists, home is the most important thing. Everyone wants a home. Five years ago, I thought that after treatment, we'd send them to a refugee camp - but everyone wanted to go back to Syria. In the early years, we saw starved children, but that's not happening any more. We haven't seen starving children for quite a while. Another change I see is that at the beginning, they were afraid when they came. They expected to see people with horns. That has completely vanished.

"Something else that is important is normality. A child needs to play and learn - these things help a lot. I thought I'd seen everything - I didn't believe how much it could help, all the clowns. They're really part of the treatment. We go into the morning meetings, and the child thinks that the clown is in charge."

"Treating Syrians is one of Israel's decisions that I appreciate the most," says Galilee Medical Center general director Dr. Masad Barhoum. "Obviously first of all for humanitarian reasons, but that's not the only thing." Like Harari, Barhoum dwells on the medical aspect and the experience he gained. "It taught me a lot," he says. "It has reinvented and shaped us as a hospital. We may be the only Western hospital in the world with experience in accepting and treating such serious wounds, and at this pace. We've made progress. Today, we reconstruct wounded people's faces, implant jaws, and print everything on a 3D printer. It brings the hospital to a higher level. We have become a leading hospital in trauma. This experience will be at the disposal of Israelis in the Third Lebanon War or a war in the north, which I think will come. We have become the frontline of medicine, and we're prepared for the worst scenario."

30-40 Syrians are currently hospitalized in Nahariya. "Putin doubled the number," Barhoum says. "We had already gone down to 20. In general, 2015 and 2016 were very tough. The injuries slowed in 2017. There are still severe injuries, but more light injuries are starting to arrive."

"WE HAVE NOWHERE TO RUN"

We are at Ziv Medical Center after breakfast time, and the doctors are arriving. Some of them are examining the children in the hall we're standing in, and some are taking children for examinations in wards. I take the opportunity to talk with some of the mothers. Obviously, none of them give their names, and none of them will agree to be photographed.

Aisha came with her five year-old grandson, who became completely deaf four years ago, following an air bombardment when he was one year old. This is her fifth time in Israel. "I feel more comfortable coming to a hospital in Israel than a clinic in Syria," she says. "The treatment there is much worse. It's better to stay home. I don't tell anyone that I was in Israel. I don't tell what I did, and no one asks. There's no government where I live - there's nothing. Only to my family do I talk about Israel and how well we're treated."

She is from a village near Daraa. "There are Russian planes above the village every day," she says. "The Russians brought no peace with them, and no ceasefire. The Russians bomb people for no reason."

"Globes": Seven years ago, did you believe this would happen?

Aisha: "We didn't believe it would be like this. Never."

Do you see any end in sight?

"It just gets worse and worse," she cries. "Now they're killing people for no reason. The children aren't studying; everyone lives in fear. Russia, Iran, Hezbollah, Israel. Everyone is bombarding in Syria. Everyone stays home all day, and everything's very expensive. Before the war, eight pitot cost 15 Syrian liras, and now they cost 100 liras (100 Syrian liras is worth NIS 0.70). Milk used to cost 100 liras; now it costs 4,000 liras, and there are no jobs at all. Anyone without land has nothing."

The second mother is from Quneitra. "It's calm there now," she says with a bitter smile. "But that's it; we've lost hope. I no longer think things will get better in Syria. There's no hope."

How can you live without hope?

"Like this - from day to day. We have nowhere to run. It's too expensive to run. What can we do? Nothing. We're home with the children every day."

When the children ask what will happen in Syria, what do you tell them?

"That there's no hope."

Go to Israel treating thousands of Syrians injured in war

'Israel is not the enemy. Bashar is the enemy,' says one patient, The Independent 8 April 2017

JUDY’S STORY - THE HEROISM OF A CANADIAN

WHO SMUGGLED JEWS OUT OF SYRIA

Born in the city of Montreal, Canada, Judy would go on to lead a clandestine operation to smuggle more than 3,000 Jews out of Syria between 1975 and 2000.

The Jerusalem Post Bradley Martin, March 19, 2020

Judy Feld Carr:

Judy Feld Carr:

I was a musicologist;

I didn’t know anything about Syria

(photo credit: JEWISH WOMEN'S ARCHIVE)

“There is one thing you have to understand as all this was taking place,” says Judy Feld Carr as she began to relay her extraordinary tale. “I cannot stress enough the secrecy of it all.”

Born in the city of Montreal, Canada, Judy would go on to lead a clandestine operation to smuggle more than 3,000 Jews out of Syria between 1975 and 2000. Yet there would be nothing in her early life to suggest that she would carry out an international human rescue mission straight out of the pages of a Tom Clancy novel. Judy was raised in the small mining town of Sudbury, nestled in the frozen wilderness of northern Ontario, where her Russian Jewish father made his living as a fur trader.

“We would live in the bush for half the year, where I learned a lot about myself. My father was the president of the Sudbury Jewish community and I was the only Jew in a Catholic elementary school,” says Judy, who was frequently the target of antisemitic attacks from fellow classmates. Judy recounted an incident in second grade when a kid accused her of killing Jesus and threw a rock at her face, smashing her bottom teeth.

“Luckily they were baby teeth,” Judy chuckles. “But these are things that always stick with you.” In 1957, she left Sudbury to study music education at the University of Toronto, earning a bachelor’s and master’s degree in musicology. Several years later, Judy would marry a young physician named Ronald Feld (Rubin) and the couple would raise three children.

Judy and her husband became involved in their Jewish community, noting with pride the fact that she became the first woman president of Beth Tzedec Congregation (1982-1983) in Toronto, one of the largest synagogues in Canada. Judy was one of the millions involved in the rescue of Soviet Jewry and one of many who sent letters to Avital Sharansky.

“Between my work with the JDL at that time, family, holding a job... my life was a little hectic to say the least!” notes Judy.

Judy came across an article from The Jerusalem Post that reported on the tragic deaths of 12 Syrian Jewish men, who ran across a minefield while attempting to flee the country to Turkey. Judy was struck by the fact that the Syrian guards callously stood by and watched them die, one by one.

“I was a musicologist, I didn’t know anything about Syria,” says Judy. “But something inside of me wanted to learn more and raise awareness.” Judy and Rubin approached the Israeli Consulate to see what they could do, where the consul instructed: “schrei gevalt” (Yiddish for “yell a lot”).

Since independence, Syria’s estimated 40,000 Jews were subject to some of the worst forms of violence and discrimination imaginable. Unlike other Arab states, Syrian Jews were not officially expelled from the country. That did not stop the government from torturing and murdering anyone attempting to flee, while holding their families hostage. Sporadic riots killed dozens of Jews and destroyed hundreds of homes, shops and synagogues. The community itself was under heavy surveillance by the Mukhabarat (Syria’s secret police) and Jews could not travel more than three km from their neighborhoods without a permit.

In 1975, Syrian president Hafez Assad explained why he refused to let the country’s Jews leave. “I cannot let them go,” he says, “because if I let them go how can I stop the Soviet Union sending its Jews to Israel, where they will strengthen my enemy?” Judy explained, given the narrow streets and where Jews were physically located, they were being leveraged as hostages against Israel.

Yet despite their perilous situation, it did not seem those in the news media were willing to yell gevalt. Following the barbaric murder of four Syrian Jewish girls (three sisters and their cousin), who were raped and mutilated while attempting to escape the country, Mike Wallace of “60 Minutes” broadcasted a segment on Syrian Jews, in which he claimed “life for Syria’s Jews is better than it was in years past” and that Syrian President Bashar Assad was “cool, strong, austere and independent.” A Jewish merchant from Damascus even claimed life was good for Syrian Jews and that any antipathy was the result of Israeli actions. It must have slipped Wallace’s mind that two members of the merchant’s own family had fled Syria while his other relatives were being interrogated in a state prison for a month.

Despite lacking a media megaphone, Rubin would chair a teach-in and Judy gave speeches on the human rights of Syria’s Jews. One of their phone calls finally came through to Syria, reaching the home of a Syrian Jewish woman who was working for the Mukhabarat. The woman’s terrified husband was the only one home at the time, leading him to divulge the phone number of Ibrahim Hamra, who would become the chief rabbi of Syria, along with the address of his school. From that point on, Judy never called Syria again.

Judy and Rubin then came up with the idea to send a telegram in French to the school, since it is a widely spoken language in Syria, asking the rabbi if he needed any religious books. Hamra replied with a list of books, which Judy proceeded to purchase in Toronto and send to him by air mail. Sadly in 1973, Rubin suddenly died of a heart attack, leaving Judy alone with their three small children.

Needing to make a living, Judy fell back to her musical training by teaching in high school and giving private lessons in the evenings. Gradually, she became more deeply involved in the rescue of Syria’s Jews. Holding three jobs, Judy went on to join the board of Beth Tzedec Congregation and the board created a fund in Rubin’s memory. In 1977, Judy married Donald Carr, a Toronto lawyer, who was one of only a handful of people who knew about her clandestine activities, along with her now six children sworn to secrecy.

“My children knew what was happening,” says Judy. “Can you imagine such a responsibility? They knew about all of the secret conversations and the rescue efforts. But they also knew never to tell anyone what they heard at home. Because if word ever got out, it would mean the difference between life and death.”

Judy and her committee quietly raised funds from Jews throughout North America to finance her activities, but her operation would expand when Hannah Cohen (a Syrian Jewish woman from Toronto) traveled to Aleppo to visit her brother who was a rabbi. Hannah was arrested and questioned for a whole day in a secret police prison but managed to smuggle in her underwear a list of rabbis, as well as a letter from them begging Judy to get the Jews out of Syria. Going forward, this would serve as a major turning point in Judy’s actions.

“Judy, you have to take my brother out of Syria!” Hannah told her friend, referring to her brother, Rabbi Eliahou Dahab. “He has cancer and does not have a long time to live.” Initially, Syrian authorities refused to allow his departure. But Judy had met an elderly couple from Aleppo who came to visit her in Toronto, and they described how Mukhabarat agents could be bribed to let Jews go. Judy began setting up her underground network to fly the rabbi to Toronto for medical treatment, as well as raising funds to pay for bribes and his airline ticket. The rabbi’s dying request was to be with his 97-year-old mother in Israel, whom he had not seen since the Jewish state declared independence in 1948.

Dahab passed away in Holon in his daughter’s house, but not before his final wish was granted. The following year, Judy rescued his daughters who were still in Syria; one of whom is now a grandmother in Bat Yam while her sister currently lives in New York.

Judy’s underground network began the rescue of individual Jews through the bribery of Syrian government functionaries, judges and even Mukhabarat officers. Remarkably, nobody in the Canadian Jewish community pressed Judy for specifics on what was being done with the raised funds. In other words, it was the best-kept secret in the Jewish world.

With each successful rescue, more individual Jews sought Judy’s help in escaping Syria. Each case was unique, since the Syrian authorities would not allow entire families to leave together. They were forced to leave immediate members of their family behind as hostages and the amount of money for the bribe would vary according to the person. But Judy also found herself needing to compose inventive excuses for granting Jews permission to leave. Some were allowed to “leave” for medical treatment, business purposes or visiting family who succeeded in leaving Syria in the 1940s and 1950s before it was illegal to do so. Each Jew allowed to leave Syria deposited money as a guarantee for his or her return, though authorities often knew full well none would return. When families were reunited, they were quietly taken to Israel by the Mossad.

“I know she [Judy] built a network of contacts in Syria,” remarked former Israeli ambassador to Canada Itzhak Shelef. “How she managed that, I don’t know.” Shelef was not alone in his astonishment, as Judy gradually worked closely with the Mossad to continue smuggling Jews out of the country, relating how former Israeli president Yitzhak Navon requested she smuggle the entire family of an Israel Air Force member. The operation turned out to be a success. Judy received official letters of recognition from former Israeli prime ministers Menachem Begin, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres.

“What the Syrian authorities did to Jews was nothing short of absolute cruelty,” says Judy when describing the tortures endured by captives held in secret prisons. “You must understand that we needed to get the Jews out of prison immediately.” Torture methods included starvation, sleep deprivation and the pulling of fingernails. Judy recounted the painful experiences of Elie Swed, who was put in an underground cell measuring one by one-and-a-half meters – for the crime of having visited his sisters in Israel. Elie was subjected to electric shocks and severe beatings. Selim, his elder brother, was later imprisoned and likewise tortured. After a considerably amount of bribery and international pressure spurred on at Judy’s behest, the two brothers would be released.

“If Jews were still in Syria, there is no doubt in my mind that one of the sides fighting in this ongoing civil war would have killed them all,” says Judy, while noting that there were few (if any) Jews left in Syria today.

Some of Judy’s most interesting stories involve the saving of priceless Jewish texts such as the Damascus Keter (a codex of the Hebrew Bible). Handwritten in 1180, it was taken to Muslim lands by Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition and was smuggled by one of Judy’s agents hidden in stacks of documents. Today, it resides in Israel’s National Library in Jerusalem. Other precious Jewish texts included an Aleppo Torah scroll and about 150 books.

“The smuggler left the silver Aleppo Torah case for the Syrians,” says Judy when describing how the scroll was smuggled out. “I only cared about getting the Torah scroll out of there.”

A total of 3,228 Jews were rescued due to Judy’s actions, many of whom live in Israel today and others places, such as Brooklyn, São Paulo, Brazil, and Panama. A considerable number have even taken to name their daughters and granddaughters “Judy” in honor of their rescuer. Despite her story finally being revealed after her being awarded the Order of Canada and the Israel Presidential Award of Distinction, among other accolades, very few in Israel have heard of the heroism of this Canadian woman who rescued Syria’s Jews.

Bradley Martin is a Senior Fellow with the News and Public Policy Group Haym Salomon Center and Deputy Editor for the Canadian Institute for Jewish Research

The true story of Eli Cohen, the Israeli agent hanged in Syria.

Jerusalem Post, September 25 2019

Despite the deterioration of the Israeli image and its standing among Western nations, it seems that the world is not tired of Israeli spies.

The recent barrage of films and series about the plots, bravery but also failures of Israel’s intelligence community is a reminder of the subject’s draw, of which this Netflix six-episode series of “The Spy” recently released is just one example.

It tells the story of Eli Cohen, who was sent in 1962 as a spy (a “combatant,” in Mossad jargon) by Unit 188 of Aman (Hebrew acronym for military intelligence) to infiltrate Syria. Later, the unit was transferred to the Mossad and changed its name to Masada, and more recently Caesarea.

The series, which stars British Jewish actor Sacha Baron-Cohen as Eli Cohen, provides mainly the Israeli version of the affair and ignores the Syrian account. It is also filled with factual errors.

Eliyahu (Eli) Cohen was born in Alexandria, Egypt, in 1924. His father, Shaul, emigrated from Syria to Egypt when Eli was seven. He studied engineering and was a member of the local Zionist movement. He played a very marginal insignificant role in the ill-fated Israeli espionage network that was smashed by the Egyptian authorities in 1954. He, like the others, was arrested, but the police found no evidence against him so he was freed.

Cohen stayed in Egypt until just after the 1956 Suez (Sinai) war, and then moved to Israel. Being fluent in Arabic, French and Hebrew, he was hired as a translator for military intelligence. Yet he declined offers to be transferred to Unit 188.

The intelligence community let Cohen go on with his life – which included his wife, Nadia (sister of writer Sami Michael), children, and his comfortable and safe desk job – until border tensions with Syria erupted in May 1960.

Now the espionage team at Unit 188 urgently required a spy in Damascus, and had an ambitious plan for preparing and planting an undercover Israeli combatant there. Cohen was the man for the job. At the beginning he continued to refuse their repeated requests but eventually accepted the offer.

Even with a sense of immediate need, his training took over half a year. A small but significant part was a vigorous course in Koran studies in Israel so as to be conversant with “fellow Muslims” when he got to Syria.

In February 1961 he arrived in the “base” country, Argentina, carrying the passport of a European country. It bore what was, for him, a temporary name.

Three and a half months later, a Unit 188 courier arrived in Buenos Aires and handed Eli Cohen his new identity as Kamel Amin Taabeth, a Syrian businessman born in Lebanon. Taabeth had been invented by Aman, and his avatar as a rich man would make this a high-budget operation for Israel’s frugal military.

For a few months Cohen blended in with the many Arab entrepreneurs in South America, and he was dazzlingly successful at meeting rich and influential members of the Syrian community there.

In January 1962, he was ready to move to the “target” country. He arrived in Beirut, and then took a two-hour taxi ride across the border into Syria, with a sophisticated, high-speed radio transmitter hidden in his luggage. Cohen/Taabeth was also carrying genuine letters of introduction, penned by Syrians in South America.

In Damascus, he instantly became the fascinating new man in town, having been recommended by everyone who was anyone in Buenos Aires. The series shows that one of his acquaintances in Argentina was the Syrian military attaché Major Amin al-Hafez, who became the president of Syria. Prominent Syrian journalist Ibrahim Hamidi rejected this claim, in a piece he wrote earlier this month, in the Asharq Al Awasat newspaper.

While running an import-export business, Cohen/Taabeth cultivated his political contacts. He arranged lavish parties at his home, with pretty women – some of them paid to be intimately entertaining for his powerful new friends. This was expensive. The Israeli spy had to have plenty of cash, as well as nerves of steel. But it paid off.

He was invited to military facilities, and he drove with army officers all along Syria’s Golan Heights, looking down at the vulnerable farms and roadways of Israel below. Cohen made a point, of course, of memorizing the location of all the Syrian bunkers and artillery pieces. He was able to describe troop deployments along the border in detail, and he focused on the tank traps that could prevent Israeli forces from climbing the heights if war were to break out. He also furnished a list of some of the Syrian pilots and accurate sketches of the weapons mounted on their warplanes.

He sent the data to Tel Aviv by tapping Morse code dots and dashes on his telegraph key, covering all areas of life in Syria. Israeli intelligence was able to get a good picture of an enemy country that had seemed impenetrable.

Ironically, one of the communications officers who handled the coded messages to and from Damascus was Cohen’s own brother Maurice. Each brother did not know that the other was working for Israeli intelligence. Eli had told Maurice that he was traveling abroad procuring goods for the Defense Ministry. But Eli, also always pining for his family, had taken to sending them greetings, and making some references to his family concealed in his Morse messages, without revealing where he was.

Eventually Maurice found out that the messages he was deciphering came from his brother in Damascus. During one of Eli’s visits he smilingly hinted that he knows what the work of his brother is. Eli was furious and complained to his handlers. Maurice was removed from his unit.

If Cohen and his Israeli controllers had only been more cautious, his chances of survival would have been higher. In November 1964 he was on leave in Israel, obviously shedding his Taabeth identity and trying to be a normal husband and father at home, awaiting the birth of his third child.

Cohen kept extending his leave and hinted that after nearly four years abroad, he might want to come in from the cold. He mentioned that he felt danger from Col. Ahmed Suedani, head of the intelligence branch of the Syrian army.

Unfortunately, Cohen’s case officers did not pay attention to the warning signs. They were too focused on preparing for conflict, because there was another bout of tension on the border. One could not be certain, but war seemed to be on the horizon. It was vital to have reliable intelligence from Damascus, and the Mossad applied pressure on Cohen to return to his espionage post as soon as possible.

In 2015, then-Mossad head Tamir Pardo told Nadia that it was wrong to send Eli back to continue his mission in Syria.

Upon returning to Damascus, Cohen forgot the rules of prudence. His broadcasts became more frequent, and in the space of five weeks he sent 31 radio transmissions. His case officers in Tel Aviv should have restrained him, but none did. The material he was sending was just too good to stop.

Even today 54 years later, Pardo admits that it is not clear what led the Syrian security services to expose Eli. There are a few explanations but all of them have never been fully verified.

One is that Colonel Suedani’s intelligence men – apparently guided by radio direction-finding equipment, most likely operated by Soviet advisers – broke into Cohen’s apartment on January 18, 1965, and caught him redhanded, tapping his telegraph key in the middle of a transmission.

Another speculation is that a piece of political gossip about Syrian politics transmitted by Cohen was given in haste to the Voice of Israel radio station and broadcast in Arabic, before it was officially announced by Damascus radio.

A third theory is that Syrian intelligence was shadowing a Syrian citizen who was suspected of working for the CIA. Cohen incidentally met him and became a suspect too.

Another clue as to why he was caught came from another spy. Masoud Buton was planted by Aman inside Lebanon from 1958 to 1962, when he quit over a financial dispute with Mossad headquarters and moved to France.

In his memoirs, Buton wrote that during his mission he was ordered to procure identity documents for a “Lebanese-born businessman of Syrian extraction.” Buton managed to do that and sent the papers of Kamel Taabeth to Unit 188. Later Buton sent a warning that the documentation might be compromised in some way. His warning was ignored. Meir Amit, the Mossad’s chief during the Cohen affair, strongly rejected Buton’s claim.

After his arrest the State of Israel immediately went into action, hoping against hope to get Eli Cohen out of Syria – or, at least, to keep him alive. The Mossad quietly hired a prominent French lawyer, who arranged official appeals to European governments and to the pope.

Syria turned a deaf ear. A court in Damascus sentenced Cohen to death, and he was hanged in a public square, to the cheers of a large crowd, on May 18, 1965. The Syrians did allow the spy to send a final written message to his family.

“I am writing to you these last words, a few minutes before my end,” he wrote. “I request you, dear Nadia, to pardon me and take care of yourself and our children. Don’t deprive them or yourself of anything. You can get remarried, in order not to deprive the children of a father.” Nadia never remarried.

Being the first and only Israeli Jew who was sent as a combatant to an enemy country and executed, Cohen has been mythologized as a super spy, whose information helped Israel to defeat the Syrian army and capture the Golan Heights in the 1967 Six Day War. Because there is a Hebrew phrase to speak kindly of the dead, no one has dared to seriously analyze Cohen’s real contribution to the 1967 war.

True, Cohen was a courageous hero and paid with his life for serving the Jewish state. But former intelligence officers also admit that Cohen’s data was only one piece of the puzzle. No less important intelligence was gathered from other sources, such as bugging Syrian telephone poles and from reconnaissance flights.

To this day, Cohen’s family – while accusing the Mossad of mistakes which led to his downfall – has also waged a public campaign for Syria to return his body for burial in Israel. The Israeli government brought up the subject through third-party envoys.

A year ago, the Mossad found the expensive watch Cohen had worn to establish his cover story and credentials as a wealthy trader.

But Bashar Assad’s dictatorship may well have been sincere in declaring privately that no one in Syria knew where Cohen was buried.

History of the Jews in Syria - Wikipedia

Syrian Jews Wikipedia

Jews of Syria Jewish Virtual Library

The Jews of Syria: A Lost Civilization Aish

Buying Lives Judy Feld Carr's Secret Rescue of Syrian Jews Chabad

Last Jewish family in Aleppo flee for Israel Telegraph, By Lauren Williams, Gaziantep 23 Nov 2015

|

|

|

CLICK BUTTON TO GO TO |

|

JUDY’S STORY - THE HEROISM |

THE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

ISRAEL, THE JEWS AND SYRIA

INCREDIBLE

Click here to see

Jewish Exiles Overview,

Population change between 1948 and 2012, Maps