|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

Germany consisted of many small states. The move towards unification gathered pace in the 19th century and was achieved under the leadership of Prussia in 1871. This process is shown in the videos below. It is important to understand this as it was the environment in which the Jews lived and eventually led to WW1, the subsequent rise of Hitler, WW2, the Holocaust and the feeling of recrimination.

HISTORY

from Wikipedia

Jewish settlers founded the Ashkenazi Jewish community in the Early (5th to 10th centuries CE) and High Middle Ages (c.1000–1299 CE). The community prospered under Charlemagne, but suffered during the Crusades. Accusations of well poisoning during the Black Death (1346–53) led to mass slaughter of German Jews and their fleeing in large numbers to Poland. The Jewish communities of the cities of Mainz, Speyer and Worms became the center of Jewish life during Medieval times. "This was a golden age as area bishops protected the Jews resulting in increased trade and prosperity." The First Crusade began an era of persecution of Jews in Germany. Entire communities, like those of Trier, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne, were murdered. The war upon the Hussite heretics became the signal for the slaughter of the unbelievers. The end of the 15th century was a period of religious hatred that ascribed to Jews all possible evils. The atrocities of Chmielnicki (1648, in the Ukrainian part of southeastern Poland) and his Cossacks drove the Polish Jews back into western Germany. With Napoleon's fall in 1815, growing nationalism resulted in increasing repression. From August to October 1819, pogroms that came to be known as the Hep-Hep riots took place throughout Germany. During this time, many German states stripped Jews of their civil rights. As a result, many German Jews began to emigrate.

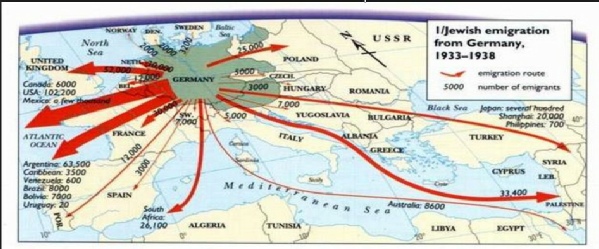

From the time of Moses Mendelssohn until the 20th century the community gradually achieved emancipation, and then prospered. In January 1933, some 522,000 Jews lived in Germany. However, following the growth of Nazism and its antisemitic ideology and policies, the Jewish community was severely persecuted. Over half (approximately 304,000) emigrated during the first six years of the Nazi dictatorship. In 1933, persecution of the Jews became an active Nazi policy. In 1935 and 1936, the pace of persecution of the Jews increased. In 1936, Jews were banned from all professional jobs, effectively preventing them from exerting any influence in education, politics, higher education and industry. The SS ordered the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht) to be carried out that night, November 9–10, 1938. The storefronts of Jewish shops and offices were smashed and vandalized, and many synagogues were destroyed by fire. Increasing antisemitism prompted a wave of a Jewish mass emigration from Germany throughout the 1930’s. There were only approximately 214,000 Jews in Germany proper (1937 borders) on the eve of World War II.

The remaining community was nearly eradicated in the Holocaust following deportations to the East. By the end of the war between 160,000 and 180,000 German Jews had been killed in the genocide officially sanctioned and executed by Nazi Germany. In the Holocaust, approximately 6 million European Jews were deported and murdered during World War II. On May 19, 1943, Germany was declared judenrein (clean of Jews; also judenfrei: free of Jews). Of the 214,000 Jews still living in Germany at the outbreak of World War II, 90% died during the Holocaust. After the war the Jewish community started to slowly grow again, fuelled primarily by immigration from the former Soviet Union and Israeli expatriates. By the 21st century, the Jewish population of Germany approached 200,000, and Germany had the only growing Jewish community in Europe.

Today, the majority of German Jews are Russian-speaking. The total estimated enlarged population of Jews living in Germany (including non-Jewish household members) is close to 250,000.

Currently in Germany it is a criminal act to deny the Holocaust or that six million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust (§130 StGB); violations can be punished with up to five years of prison. In 2007, the Interior Minister of Germany, Wolfgang Schäuble, pointed out the official policy of Germany: "We will not tolerate any form of extremism, xenophobia or anti-Semitism." In spite of Germany's measures against right-wing groups and anti-Semites a number of incidents have occurred in recent years.

19th CENTURY JEWISH EMANCIPATION

From Centre for Israel Education

The process of Jews receiving political emancipation in Europe began with Napoleon’s conquest of the continent at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. With Napoleon, the concepts of liberty, fraternity and equality spread into Central Europe. A setback for attainment of Jewish equal rights in German lands followed Napoleon’s defeat and a return of conservative leaders and ideology. This reality resulted in many German states rescinding previously granted Jewish rights following the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815.

In March 1848, a series of popular revolutions broke out in German lands against the power of the independent states. The 1848 revolutions pushed for the spread of liberal democratic principles, including emancipation for the Jews. Despite the failure of the revolutions to create a unified Germany in 1848, the groundwork for Jewish equality had been laid in the short-lived March 1849 Frankfurt Parliament.

In July 1869, Prussian King Wilhelm I promulgated the North German Confederation Constitution, which gave Jews civil and political rights in twenty-two German states. This Constitution was adopted by the new German empire upon its establishment on April 14, 1871. On April 22, 1871, the Jews in all of Germany were finally given emancipation when the Constitution was extended to Bavaria.

The process of Jewish emancipation led to many changes in both Jewish and non-Jewish society. Some Jews continued religious identification with non-Orthodox Judaism, seeking to remain Jewish but more like their Christian peers; some converted to Christianity because the Emancipation of 1871 still prevented Jews from gaining access to certain high profile social positions; others simply assimilated. Emancipation also led to new and more virulent forms of antisemitism, a term that was coined in 1879 in a pamphlet by Wilhelm Marr. Marr became the father of virulent racial antisemitism, singling out Jews as inferior because of their racial impurity.

THE JEWISH REFORM MOVEMENT

From Aish: (History Crash Course #54:) by Rabbi Ken Spiro

Author's note: This section on the Reform Movement is meant as an overview of the origins and history of the movement. It is not meant to reflect the modern attitude of the Reform Movement nor its present-day adherents.

Nearly 200 years after the founding of the first Reform congregations, the movement has gone through a significant metamorphosis. The failure of an enlightened Europe to end antisemitism; the Holocaust; the birth of the State of Israel and the high rate of intermarriage and assimilation among successive generations of Reform Jews has led to what can only be termed a dramatic about face in the Reform attitude toward both Jewish observance and Jewish national identity. These monumental changes are best reflected in The Statement of Principles for Reform Judaism adopted by the CCAR (Central Conference of American Rabbis) May 1999. President Rabbi Richard Levy called for an increased commitment to observance, Torah study and Israel, a radical departure from previous CCAR platforms.

While the ideological differences between Orthodox and Reform remain enormous, these changes clearly reflect the modern Reforms Movement's recognition of what has shown to be a historically proven reality: What has kept Jews Jewish for thousands of years is a commitment to Judaism ― its study, observance, and the primacy of Judaism as a central component of every Jew's identity.

The Enlightenment (1650-1850) Aish - History Crash Course #53 was from the middle of the 17th century and marked the end of the Renaissance. The new ideology that emerged in the post-Renaissance period was an ideology that still permeates the Western world to a large extent. We have to understand this ideology and the Jewish people's relationship to it in order to make sense out of what happens next in Jewish history

This was a period of time characterized by breakthroughs in thinking which steered the world away from religion and more and more toward secularism, humanism, individualism, rationalism, and nationalism and gave Jews new rights ― human rights and citizenship rights ― which they never had before. After centuries of physical and economic marginalization, the intoxicating allure of emancipation proved overwhelmingly attractive to many Jews in Western Europe. Many desired nothing more than to prove their loyalty to their host country and the best way to do this was to join the army, which for centuries had been closed to Jews. In Prussia and later Germany, disproportionately large numbers of Jews volunteered for military service. To quote David Friedlander, a Jewish volunteer in the Prussian army during the Napoleonic wars:

...[it was] a heavenly feeling to possess a fatherland! What rapture to be able to call a spot, a place, a nook one's own upon this lovely earth....Hand in hand with your fellow soldiers you will complete the great task; they will not deny the title of brother for you will have earned it."

The new broad-mindedness went so far that Jews were even accepted into society as long as they were not "too Jewish" ― as long as they didn't dress too differently, behave too differently, eat a different diet, or insist on wearing their "old-fashioned" religion on their sleeve.

The reaction to this from some Jews was a staunch refusal to cooperate and get with the plan ― in any way, shape or form.

But there was also the opposite reaction from others. These Jews went along with the spirit of liberation and modernity and dropped the things that had made them different from other people ― such as keeping kosher, keeping Shabbat, etc.

Of course, as soon as Jews drop their religion, they begin to assimilate. Intermarriage rates climbed dramatically. In Germany, for example they rose from 8.4% in 1901 to 30% by 1915. Marginal Jewish identity and assimilation became the norm during the 19th century. While we don't have exact figures for the rate of assimilation, what we do know is that an estimated quarter of a million Jews converted to Christianity during this time and that countless others assimilated into the European culture.

Interestingly, the assimilation rate was higher where there were fewer Jews. In Eastern Europe, where the Jewish population was almost 5 million, 90,000 (or not quite 2%) converted to Christianity in order to have an easier life and mingle with mainstream society. But in Western Europe where there were fewer Jews, the proportions were much higher. The majority of the Jews of France assimilated, as did the majority of the Jews of Italy and Germany.

Why? Because in Western Europe, the governments were more liberal and open, Jews were granted citizenship and the non-Jews were generally less hostile so the attraction to assimilate and join the mainstream was much greater.

Some Jewish converts to Christianity were very famous. In Part 53, we already mentioned Benjamin Disraeli, the British Prime Minister who became the great architect of Victorian imperialism. But we must also mention Karl Marx, the father of Communism.

Marx was converted by his father at age six; the father had converted a few years earlier in order to be able to practice law. Marx, who eventually became an atheist, is the author of The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital, ironically called the "Bible of the Worker." He is also famous for calling religion "the opiate of the masses."

A terrible example of a self-hating Jew, Marx blamed all the world problems on the Jews in his rage-filled A World without Jews. Virulent hatred of Judaism and other Jews was not uncommon to such converts. It infected, among others, Heinrich Heine, one of the greatest figures in 19th century German literature.

Heine converted, as did so many, for pragmatic reasons, explaining his conversion: "From the nature of my thinking you can determine that baptism is a matter of indifference to me and I do not regard it as important even symbolically. My becoming a Christian is the ticket of admission to European culture." He was as cynical about Judaism, declaring it one of the world's three greatest evils (along with poverty and pain.)

THE GERMAN JEWISH REFORM MOVEMENT

(Note: The use of Reform in other countries is sometimes confusing. For example the the Reform movement in Britain did not directly evolve from the Reform Judaism that originated in Germany. However, British Reform and the German classical reform movement both arose from a period of reformation and reaction to traditional practices and are accepted as part of wider Progressive Judaism. (See Wikipedia)

One of the more dramatic reactions to the changes of this time period came from a group of German Jews who formed what came to be known as the "Reform Movement."

The German Jews who began the Reform Movement in the early 1800’s wanted to maintain some connection to Judaism, but at the same time wanted to take advantage of the newly-won rights and freedoms, which were available only if one became a full-fledged member of European society. Traditional Jewish lifestyle such as kashrut (food laws), shabbat observance and national identity were viewed as barriers to this acculturation. So these German Jews set about dropping some key aspects of traditional Judaism. The most dramatic of these was the belief that the Torah was given to Jews by God at Mount Sinai.

For 3,000 years Jews never questioned that the Torah came from God. The various sects that developed ― such as the Sadducees and the Karaites ― questioned the oral tradition or rabbinic law, but never the Divine origin of the Torah. This was an earth-shattering precedent.

The first crack in the dam came from Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786), a brilliant intellect who was known as the "hunchback philosopher". Although an observant Jew in terms of his lifestyle, he advocated the "rational" approach to religion, as he wrote in his Judaism as Revealed Legislation:

"Religious doctrines and propositions ... are not forced upon the faith of a nation under the threat of eternal or temporal punishment but in accordance with the nature and evidence of eternal truths recommended to rational acknowledgment. The Supreme Being has revealed them to all rational creatures."

In effect, Mendelssohn was following the pattern of the thinkers of the Enlightenment, the "Age of Reason." Religion should be rational. If the law of God seems irrational, then man must follow reason. (Mendelssohn's children were not observant and within a few generations they had either assimilated or converted. Mendelssohn's grandson, the famous German composer Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, was baptized as a child by his assimilated parents.)

By opening up Judaism to this kind of rational scepticism, Mendelssohn opened the door through which others rushed in.

This is not to suggest that before him Judaism was closed to inquiry. Indeed, asking questions was always a big part of Judaism, but it was was grounded in certain beliefs and assumptions, which in the Reform Movement came tumbling down.

The first Reform service was conducted by Israel Jacobson in his school chapel in Seesen, Germany in 1810, and it was adopted by the first Reform synagogue which opened in Hamburg in 1818.

The Reform service had a choir, robes, and an organ; it was conducted in German with German songs and German prayers in a deliberate attempt to emphasize nationalistic loyalty and identity and to make synagogue worship resemble as much as possible to the mainstream German Protestant service.

The New Israelite Temple Association-Hamburg Dec. 1817:

...the worship service shall be conducted on Sabbath and holy days....Specifically, there shall be introduced at such services a German sermon, and choral singing to the accompaniment of a organ....it shall apply to all those religious customs...which are sanctified by the church.

For Jewis, however, this was quite a departure. Up until then, Jews prayed in Hebrew, reciting the prayers composed by the Men of the Great Assembly and by the Sanhedrin some two thousand years earlier. Jews never played musical instruments during Shabbat services, and certainly not an organ which was an instrument common to Christian churches, as was the choir and the robes.

Not long after, the Reform Movement switched Shabbat from Jewish Saturday to Christian Sunday, and came to call its synagogues "temples" to underscore the point that Reform Jews no longer looked to the rebuilding of "The Temple" in Jerusalem.

In fact, Reform leader Samuel Holdheim (1806-1860), who became the head of the Reform congregation in Berlin, argued against the mention of Jerusalem, Zion, or the land of Israel during services. He opposed circumcision, wearing of skull caps or prayer shawls, or the blowing of the shofar ― in short just about anything traditionally Jewish.

Another Reform leader Abraham Geiger (1810-1874), who led reform groups in Breslau, Frankfurt and Berlin, called circumcision "a barbaric act of blood-letting rite" and advocated against "the automatic assumption of solidarity with Jews everywhere."

These were big breaks with tradition. Ever since Abraham, circumcision was the way Jews marked their covenant with God. And Jews helping each other in times of trouble ― one for all and all for one ― was seen as an integral part of Jewish nature as defined by God.

Reformers of Germany declared that they were not members of the nation of Israel but "Germans of the Mosaic persuasion."

The philosophy of the German Reform Movement evolved further at conferences held in Brunswick in 1844 and in Frankfurt in 1845. Here are excerpts that show how much the Jews of Germany wanted to show their allegiance to their country of residence, which meant disavowing any allegiance to the Land of Israel or the Hebrew language:

Reform Rabbinic Conference-Brunswick 1844:

For Judaism, the principal of human dignity is cosmopolitan, but I would like to put proper emphasis on the love of the particular people [among whom we live] and its individual members. As men, we love all mankind, but as Germans, we love the Germans as the children of the fatherland. We are, and ought to be patriots, not merely cosmopolitan.

Reform Rabbinic Conference-Frankfurt-1845:

By considering Hebrew as being of central importance to Judaism, moreover, one would define it as a national religion. Because a separate language is a characteristic element of a separate nation. But no member of this conference, the speaker concluded, would wish to link Judaism to a particular nation.

The hope for national restoration contradicts our feelings for the fatherland...The wish to return to Palestine in order to create there a political empire is superfluous...But Messianic hope, truly understood is religious...This later religious hope can be renounced only by those who have a more sublime conception of Judaism, and who believe that the fulfilment of Judaism's mission is not dependent on the establishment of a Jewish state, but rather by the merging of Jewry into the political constellation of the fatherland. Only an enlightened conception of religion can replace a dull one....This is the difference between strict Orthodoxy and Reform: Both approach Judaism from a religious standpoint: but while the former [Orthodox] aims at restoration of the old political order, the later [Reform] aims at the closest possible union with the political and national union of out times.

(For more on this subject, see History of the Jews by Paul Johnson, pp. 333-335, and Triumph of Survival by Berel Wein pp. 52-53, and The Jew in the Modern World ed. by Paul Medes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz pp. 161-177.)

Along the way, the members of Reform Movement coined a new term to describe those who stuck to traditional Judaism ― they called them the "Orthodox" which implied of course that observant Jews were backward-a relic of the past, as opposed to "Reform" who were forward thinking, modern and progressive.

The Orthodox Jews were basically run out of town. In Frankfurt am Main, one of the oldest Jewish communities in Europe, only about one hundred observant families remained by the middle of the 19th century.

Why?

The German Reformers were afraid that while they might be able to assimilate into the larger German culture, as long as there continued to exist a group of Jews who chose to act as Jews and openly identify as such ― that is, Jews who irked the Germans ― then the Germans would lump everyone together and continue to be hostile toward them as well.

But of course the Jews who would not go along with the Reform Movement weren't about to take all this sitting down.

The leader of the Orthodox counter-attack against the Reform Movement was a rabbi by the name of Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808 to 1888). Hirsch was born in Hamburg and after completing his rabbinic studies he attended the University of Bonn. He served as a Rabbi in several communities and as the chief rabbi of Moravia, a community of 50,000 Jews. He published several well-known works such as Horeb in which he sought to demonstrate the viability of traditional Judaism in the modern world.

In 1851 he moved to Frankfurt am Main, to serve as Rabbi of the shrinking community and wage the philosophical counteroffensive to the Reform movement.

As part of his fight he succeeded in setting up his own Orthodox institution in Frankfurt which is called the Kahal Adas Yeshurin, and he created his own religious school system.

His aim was to show those Jews who wanted to be modern that it was possible ― all within the context of traditional Judaism. There is no need to drop Torah in order to get along in an evolving world as the Torah makes provisions for all that. This is what he wrote in 1854 in an article entitled, "Religion Allied to Progress" (see Collected Writings of Samson Raphael Hirsh):

"Now what is it that we want? Are the only alternatives either to abandon religion or to renounce all progress? We declare before heaven and earth that if our religion demanded that we should renounce what is called civilization and progress we would obey unquestioningly, because our religion is for us the word of God before which every other consideration has to give way. There is, however, no such dilemma. Judaism never remained aloof from true civilization and progress. In almost every area its adherents were fully abreast of contemporary learning and very often excelled their contemporaries. An excellent thing is the study of Torah combined with the ways of the world."

What Rabbi Hirsch emphasized was that the normal Jewish way to be is to be fully in the world but also to be fully immersed in Torah. It is not a question of "either Torah or the World" ― it's a question of priorities. He made it very clear that the first priority is Torah. In contrast to Mendelssohn, he said that even if you didn't understand some part of the Torah, you had to follow it anyway because it is the word of God.

(For more on this subject see Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch: Architect of Torah Judaism for the Modern World by Elijahu Meir Klugman.)

Despite the efforts of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch and others, the Reform Movement spread, not just inside Germany but to other countries as well, though each group of Reformers had its own take on it. For example, the Reform Jews of England in the West London Synagogue adopted a quasi-Karaite position. They stuck to the Torah as the word of God, but rejected the teachings of the Talmud.

In America, the Reform Movement also took on its special character after it was transplanted there from Germany by several hundred thousand German immigrants in the mid-19 th century. We will take a look at it when we take up the Jewish life in America.

Jews of 19 th century Germany founded the reform movement, rejecting the idea of a Jewish nation and proclaiming themselves "Germans of the Mosaic faith." The reform movement of those days was a compromise between total apostasy (assimilation) and orthodoxy. Orthodox Jews often confounded Reform Judaism with assimilation, but they are not the same. This brief essay does not explore the entire theological roots of the reform movement, past or present, and is restricted to examination of the past history of anti-Zionism in reform Judaism, in order to better understand how this history influenced current ideology of anti-Zionist Jews.

Reform Judaism was motivated by many different spiritual and practical factors. Indeed there was strong drive to "fit in" to modern society, taking advantage of the opportunities offered by the emancipation of the Jews in Europe, as well as an honest attempt to reconcile religion with the findings of science and rationality. Clearly Jews cloaked in the garb of the ghetto labelled themselves as different. At the same time, there was a wish to maintain a tie to an undefined or redefined Jewish identity. A part of the reform platform however, had nothing to do with modernization.

The nature of the Jewish identity, whatever it might be was not nationalist according to 19th century reform Judaism. For every other nation in Europe, modernization and nationalism went hand in hand. Yet just as every other nation was discovering its identity, reform Jews were trying to lose theirs, in the name of the same modern rationalism. They did not want to appear to be different, or to have their loyalty called into question because their allegiance might be to another people. The opposition of reform Jews to idea of a Jewish people and the centrality of Zion to Jewish life predated political Zionism by many years. In the USA, in 1841, at the dedication ceremony of Temple Beth Elohim in Charleston, South Carolina, Rabbi Gustav Posnanski stated that "this country is our Palestine, this city our Jerusalem, this house of God our Temple."

The Frankfort-on-the-Main Conference of Rabbis on July 15-28, 1845, decided to eliminate from the ritual "the prayers for the return to the land of our forefathers and for the restoration of the Jewish state."

The great opposition to Zionism was not really religious or ethical, but rather a fear that Jews would once again be singled out as "different" and therefore subject to persecution:

Adolf Jellinek, who became known as the greatest Jewish preacher of his age and a standard bearer of Jewish liberalism from his position as rabbi at the Leopoldstadt Temple in Vienna, deplored the creation of what he called a "small state like Serbia or Romania outside Europe, which would most likely become the plaything of one Great Power against another, and whose future would be very uncertain." This, however, was not the real basis for his opposition. He argued that it threatened the position of Jews in Western countries and that "almost all Jews in Europe" would vote against the scheme if they were given the opportunity. He stated:

"We are at home in Europe and feel ourselves to be children of the lands in which we were born, raised, and educated, whose languages we speak and whose cultures constitute our intellectual substance. We are Germans, Frenchmen, Englishmen, Hungarians, Italians, etc. with every fibre of our being. We long ago ceased to be genuine full- blooded Semites in the sense of a Hebrew nationality that has long since been lost."

Before any Jewish state could threaten Jellinek's precious Austrian identity, his notion that Jews are at home in Europe was to be destroyed in the Holocaust. He may have thought he was a German or a Hungarian "in every fibre" of his being but the SS and Gestapo would find many non-Aryan fibers in Austrian Jews, and their being would come to an end.

The Balfour Declaration, in which Britain promised the Jews a "national home" in Palestine, alarmed British Jews, who exerted great pressure on the British government to alter or retract the document (see Edwin Montagu - Opposition to the Balfour Declaration).

The rise of Nazism brought an end to a central illusion of reform Judaism, that it was possible to become citizens of the "Mosaic faith" who would dwell in safety in a secular European society, in which they could be "Germans, Frenchmen, Englishmen, Hungarians, Italians, etc. with every fibre of our being." At the same time, it was evident that the heat of the holy land had not been so harmful to the Jewish body and soul as Rabbi Kaufmann had predicted, and that a vibrant, if struggling Zionist community had formed there. The Columbus Platform of 1937 repudiated the Pittsburgh platform, stating:

In the rehabilitation of Palestine, the land hallowed by memories and hopes, we behold the promise of renewed life for many of our brethren. We affirm the obligation of all Jewry to aid in its upbuilding as a Jewish homeland by endeavoring to make it not only a haven of refuge for the oppressed but also a center of Jewish culture and spiritual life.

The conversion of reform Judaism to Zionism was effected slowly thereafter. It gradually became apparent to most reform Jews as well as to other sceptics that Israel had become a major part of Jewish identity and center of Jewish culture. By 1999, the Reform movement had adopted the following wording regarding Israel at their Pittsburgh convention:

We are committed to (Medinat Yisrael), the State of Israel, and rejoice in its accomplishments. We affirm the unique qualities of living in (Eretz Yisrael), the land of Israel, and encourage (aliyah), immigration to Israel.

In fact, some reform Jews now took the lead in supporting the Zionist cause, most notably perhaps, Rabbi Abba Hillel Silver.

THE GERMAN JEWISH SOLDIERS OF WW1

From: History Today The German-Jewish Soldiers of the First World War in History and Memory by Tim Grady, Liverpool University Press by Leslie Jones is Deputy Editor of The Quarterly Review

SIn October 1935 Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels peremptorily announced that ‘It is forbidden to list the names of fallen Jews on memorials and memorial plaques for the fallen of the world war.’ According to Nazi ideology a Jew, even a Jew who had died for Germany, was not a real German. Following Goebbels’ edict, some war memorials duly underwent ‘Aryanisation’. At Heilbronn a memorial was dedicated in March 1936, but the names of the Jewish war dead had been chiselled out and replaced with those of First World War battles.

In August 1914 the leading institutions of the German-Jewish community had endorsed the patriotic cause. A Berlin orthodox synagogue introduced a special prayer imploring God to ‘Help our king … our people, [and] … our fatherland’. In the ensuing conflict 100,000 German Jews enlisted. Yet, as conditions deteriorated, antisemitism flourished. Jews were accused of profiteering, of avoiding military service, even of spying. In October 1916 War Minister Adolf Wild von Hohenborn, a Prussian, under pressure from antisemitic groups, commissioned a census of Jewish soldiers to ascertain how many were serving at the front. The ZVfD (Zionist Organisation for Germany) rightly considered this initiative ‘a flagrant abuse of the honour and the civic equality of German Jewry’.

__________________________________________________________________________

From Wikipedia

Judenzählung (German for "Jewish census") was a measure instituted by the German Military High Command in October 1916, during the upheaval of World War I. Designed to confirm accusations of the lack of patriotism among German Jews, the census disproved the charges, but its results were not made public. However, its figures were leaked out, being published in an antisemitic brochure. The Jewish authorities, who themselves had compiled statistics which considerably exceeded the figures in the brochure, were not only denied access to the government archives but also informed by the Republican Minister of Defense that the contents of the antisemitic brochure were correct. In the atmosphere of growing antisemitism, many German Jews saw "the Great War" as an opportunity to prove their commitment to the German homeland.

The census was seen as a way to prove that Jews were betraying the Fatherland by shirking military service. According to Amos Elon,

"In October 1916, when almost three thousand Jews had already died on the battlefield and more than seven thousand had been decorated, War Minister Wild von Hohenborn saw fit to sanction the growing prejudices. He ordered a "Jew census" in the army to determine the actual number of Jews on the front lines as opposed to those serving in the rear. Ignoring protests in the Reichstag and the press, he proceeded with his head count. The results were not made public, ostensibly to "spare Jewish feelings." The truth was that the census disproved the accusations: 80 percent served on the front lines."

The official position was that the census was intended to discredit growing anti-semitic sentiments and rumors. However, the evidence indicated that the government's intention was the opposite: to acquire confirmation of the purported ill deeds.

There was a long history of Jews in Germany being discriminated, oppressed and denied rank within the military and other government institutions. This fact substantiates the "less than eager to serve" attitude of Jews in Germany.

Results and reactions

"12,000 Jewish soldiers died on the field of honor for the fatherland"

was a leaflet published in 1920 by German Jewish veterans

in response to accusations of the lack of patriotism

The episode marked a shocking moment for the Jewish community, which had passionately backed the War effort and displayed great patriotism; many Jews saw it as an opportunity to prove their commitment to the German homeland. Over 100,000 had served in the Army; 12,000 perished in battle, while another 35,000 were decorated for bravery.

That their fellow countrymen could turn on them was a source of major dismay for most German Jews, and the moment marked a point of rapid decline in what some historians called "Jewish-German symbiosis." Judenzählung, denounced by German Jews as a "statistical monstrosity", was a catalyst for intensified antisemitism.The episode also led increasing numbers of young German Jews to accept Zionism, as they realized that full assimilation into German society was unattainable.

German Jewish writer Arnold Zweig, who had volunteered for the army and seen action in the rank of private in France, Hungary and Serbia, was stationed at the Western Front when the Judenzählung census was undertaken. Zweig wrote in a letter to Martin Buber, dated February 15:

"The Judenzählung was a reflection of unheard sadness for Germany's sin and our agony... If there was no antisemitism in the Army, the unbearable call to duty would be almost easy."

Shaken by the experience, Zweig began to revise his views on the war and to realize that it pitted Jews against Jews. Later he described his experiences in the short story Judenzählung vor Verdun and became an active pacifist.

__________________________________________________________________________

The end of hostilities brought little relief. Many Germans held Jews responsible for both defeat and revolution. The fact that some of the revolutionary leaders were Jewish, notably Kurt Eisner and Rosa Luxemburg, encouraged some commentators to contend that the German army had not been defeated but undermined from within (the myth of the ‘stab in the back’ or Dolchstoss Legende).

‘All Jews are shirkers’ was a recurrent motif. The Völkischer Beobachter offered a thousand marks to anyone who could name a Jewish mother who had had three sons at the front for more than three weeks. In 1919, in similar vein, Otto Armin (the pen name of Alfred Roth) published what he claimed were the results of the War Ministry census. According to Armin they showed that, for every Jewish soldier who had died, over 300 non-Jewish Germans had been killed. ‘The notion of the selfless devotion to the people and the fatherland has no place among them’, he concluded. Jacob Segall refuted Armin’s allegations, pointing out that 12,000 German-Jewish soldiers had died during the war. The RJF (Association of Jewish Frontline Soldiers) also highlighted their military contribution.

Concerning the commemoration of German-Jewish soldiers’ wartime endeavours, the author identifies two contrasting narratives. On the one hand there were the ‘aggressive myths of the war experience’, elaborated by the National Socialists and others. These ‘sectional narratives of the conflict’ downplayed or disputed their contribution. In Mein Kampf Hitler claimed that they had completely avoided front-line service. In October 1933 the Kyffhäuserbund, an ex-serviceman’s association aligned with the National Socialists, duly removed Jewish veterans from its membership list. When the Tannenberg National Memorial Association issued guidelines for a design competition in 1925, only German and German-blooded architects were invited to apply.

But Dr Grady also identifies a ‘national conservative’ reading of the German-Jewish soldiers’ wartime sacrifice. According to President Paul von Hindenburg, anyone ‘good enough to fight and to die for Germany’ should be exempted from the 1933 law which removed Jews from public service. In July 1934 Hindenburg also insisted that a new war medal be awarded to all ex-servicemen or their surviving relatives with no racial or religious exceptions.Although Hitler wanted to become a military dictator, he saw that he would be unable to take the country by force. He now knew that he would have to use legal and democratic methods. While in prison, he wrote his book Mein Kampf, in which he set out his political ideas and developed his antisemitic ideas.

HITLER AND ANTI-SEMITISM

From: The Holocaust Explained

Although Hitler wanted to become a military dictator, he saw that he would be unable to take the country by force. He now knew that he would have to use legal and democratic methods. While in prison, he wrote his book Mein Kampf, in which he set out his political ideas and developed his antisemitic ideas.

Following Germany’s defeat in the First World War, Hitler became convinced that people in Germany - particularly Jews - had worked against the country to achieve their own ends. Hitler felt that, as Germany continued to suffer throughout the 1920’s, drastic action was required to save the country. From his experiences both with the army and later with the NSDAP, Hitler learned to persuade others with his speeches.

Mein Kampf did not contain any new ideas. Many people in the 19th and 20th centuries had believed that races were not equal, and that some people were stronger or better than others.

Hitler took on these ideas, and stated that Germans were part of a race called ‘Aryans’ who were superior to all others and would one day rule the world. In Hitler’s view, Jews were a separate race and could not be German. He believed the Jews conspired against Aryans to rule the world for themselves.

As some of the most prominent German communists had been Jewish, Hitler believed Jews had created communism to destroy the Aryans. His aim became to destroy communism and the Jews.

(From: Imperial War Museum, London, Holocaust Exhibition, 1915)

Antisemitism - hatred of the Jews - was central to the Nazis' world -view. They believed that the world was locked in a great struggle between two races, the 'Aryans 'and the 'Semites'.

Everything the Nazis hated - Communism, liberalism, Jewish and Christian ideas of tolerance and humility- was in their view due to the influence of the 'Semitic race', the Jews. They claimed that the 'Aryan race' - white Europeans - once noble warriors, had been weakened and corrupted by this influence, whose elimination they saw as their most important task

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Nazis' built on an ancient tradition of antisemitism that was already very widespread. They found supporters throughout Europe.

Most European Jews lived in Eastern Europe, where violence often took the form of violent riots called pogroms. Waves of pogroms struck the Russian Empire between 1903-7 and again in 1920-1921, killing tens of thousands of Jews. Later Hungary, Romania and Poland passed anti-Jewish laws.

Antisemitic movements flourished in most countries. Riots had accompanied the Dreyfus affair in France. In Britain famous writers such as Rudyard Kipling, GK Chesterton and TS Eliot expressed anti-Jewish prejudice. In the 1930's Sir Oswald Mosley's British Union of Fascists carried out violent attacks on Jews.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Nazis funded their state on the idea that there was a Master Race superior to all others.

The Master Race' (Herrenvolk) was made up of the Germans and their neighbours in northern Europe, especially the blond and blue-eyed 'Nordics' . The dark haired people of southern Europe were considered inferior, though still 'Aryans'. Below them were people regarded as 'subhumans' (Untermenschen): the Slavs to the east, Gypsies and non-whites. At the very bottom - inferior, yet powerful, the eternal enemy of the 'Aryan race' - were the Jews.

The Nazis claimed that 'inferior races' threatened to subvert 'Aryan' culture' and pollute 'Aryan' bloodlines. They wanted to cleanse Germany - and Europe of such supposedly alien influences.

BLOOD PURITY AND NAZI GERMANY

The History Learning Site 9 Mar 2015

Citation: C N Trueman "Blood Purity And Nazi Germany"

Blood purity was very important to the leaders of Nazi Germany. According to Hitler, blood purity would ensure the survival of the Aryan race and the ‘1000 Year Reich’. Laws were introduced to ensure blood purity within Nazi Germany and anyone who acted outside of these laws was deemed to have committed the crime of ‘rassenschande’, which translates roughly as ‘racial pollution’ or ‘racial crime’.

“Blood mixture and the resultant drop in the racial level is the sole cause of the dying out of old cultures; for men do not perish as a result of lost wars, but by the loss of that force of resistance which is contained only in pure blood. All who are not of good race in this world are chaff. And all occurrences in world history are only expression of the races’ instinct for self-preservation. What we must fight for is to safeguard the existence and reproduction of our race and our people, the sustenance of our children and the purity of our blood, the freedom and independence of the fatherland, so that our people may mature for the fulfilment of the mission allotted it by the creator of the universe. Those who are physically and mentally unhealthy and unworthy must not perpetuate their suffering in the body of their children.” Hitler in ‘Mein Kampf’.

At the start of the Nazi regime there was a degree of reticence as to what constituted a ‘blood crime’ that led to ‘blood defilement’. Roland Freisler, the future head of the feared People’s Court, stated in 1933 that any Aryan who had a relationship with any non-Aryan was guilty of ‘blood treason’; his comment was specifically targeted against the Jews. However, in the early days of Nazi rule, such a view did not receive wide support – not even from Hitler. Many were wary as the Nazis had yet to state what exactly a ‘blood crime’ was. Some were more cautious in their approach and argued that legislation might penalise those who simply were unaware that they might have distant Jewish blood in their family. Local Nazi officials took it upon themselves to ban those who wanted to proceed with what they deemed to be mixed marriages. But even in 1934, more than a year into power, a senior Nazi, William Frick, ordered these local officials to be more cautious. It was only in 1935 that Frick gave his support to those officials who used their local authority to delay such marriages.

The 1935 Nuremberg Laws finally gave clarity to ‘blood purity’ when mixed marriages and any form of relationship between Aryans and Jews was outlawed. Anyone classed as an Aryan who was caught engaging in a relationship with a Jew after the passing of the Nuremberg Laws faced a prison sentence. Any Jew caught breaking the laws faced a lengthy sentence in a concentration camp with no guarantee that he/she would be released. Freisler had finally got his way as ‘blood treason’ was now on the statue book.

However, the Nuremberg Laws created a problem that Frick had been concerned with in 1934. What about Aryan/Jewish marriages that had taken place before the Nuremberg Laws were passed? The laws did not nullify such marriages but under Nazi ideology any children born in such marriages could not be pure Aryan. The Nazi government approached this issue very simply: for a regime that preached the importance of marriage and family, it encouraged the Aryan partner in such a marriage to divorce.

The desire for blood purity continued into World War Two when anyone in Germany caught having sexual relations with any slave labourer brought into the country faced severe punishment.

The Nazi propaganda machine constantly pushed home the importance of blood purity. All avenues of themedia were used to spread the message. The Office of Racial Purity frequently wrote about the “honour of the German people” and how it could be diluted by “unacceptable relationships”. Films shown across Germany portrayed male Jews as sexual predators who abused the young women of Germany. There was a constant push to remind all those in Germany about the importance of blood purity and the consequences of ‘racial crimes’ or ‘blood treason’.

Education played an important part in spreading the message of ‘blood purity’. School teachers were given a very specific brief to teach. The Nazis assumed that by the time young children had grown up, they would accept blood purity as a normal and natural part of life. Older girls were warned about the dangers of engaging in a relationship with a non-Aryan. A pamphlet titled “The German National Catechism” was widely available in all schools. It gave a stark warning to girls who ignored the advice. It warned that a child born into a “mixed-marriage” would be a “lamentable creature, tossed back and forth between the blood of his two races”. It continued that “a woman defiled by a Jew can never rid her body of the foreign poison she has absorbed. She is lost to her people.” Children were taught to memorise poems about blood purity. They were told “keep your blood pure” as it is “your eternal life”.

The imagery of pure blood played a very important part in Nazi ceremonies. Hitler used the issue of spilt pure Aryan blood at the annual Nuremberg rallies. The so-called ‘Blood Banner’ (Blutfahne) was a special Nazi flag that had been supposedly drenched in the blood of “Nazi martyrs” at the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. Each year at Nuremberg, Hitler would accept new party colours with one hand holding the new colours while his other hand grasped the ‘Blood Banner’. The Blood Order’ (Blutorden) was the highest honorary decoration given out by the Nazi Party and it was awarded to those still alive in 1933 who had participated in the Beer Hall Putsch – about 1500 in total.

GERMAN JEWS DURING THE HOLOCAUST, 1939–1945

From: Holocaust Encyclopedia (see also Holocaust)

In January 1933, some 522,000 Jews by religious definition lived in Germany. Over half of these individuals, approximately 304,000 Jews, emigrated during the first six years of the Nazi dictatorship, leaving only approximately 214,000 Jews in Germany proper (1937 borders) on the eve of World War II.

In the years between 1933 and 1939, the Nazi regime had brought radical and daunting social, economic, and communal change to the German Jewish community. Six years of Nazi-sponsored legislation had marginalized and disenfranchised Germany's Jewish citizenry and had expelled Jews from the professions and from commercial life. By early 1939, only about 16 percent of Jewish breadwinners had steady employment of any kind. Thousands of Jews remained interned in concentration camps following the mass arrests in the aftermath of Kristallnacht (Night of the Broken Glass) in November 1938.

WORLD WAR II

Yet the most drastic changes for the German Jewish community came with World War II in Europe. In the early war years, the newly transformed Reich Association of Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland), led by prominent Jewish theologian Leo Baeck but subject to the demands of Nazi German authorities, worked to organize further Jewish emigration, to support Jewish schools and self-help organizations and to help the German Jewish community contend with an ever-growing mass of discriminatory legislation.

Following the outbreak of war on September 1, 1939, the government imposed new restrictions on Jews remaining in Germany. One of the first wartime ordinances imposed a strict curfew on Jewish individuals and prohibited Jews from entering designated areas in many German cities. Once general food rationing began, Jews received reduced rations; further decrees limited the time periods in which Jews could purchase food and other supplies and restricted access to certain stores, with the result that Jewish households often faced shortages of most basic essentials.

German authorities also demanded that Jews relinquish property “essential to the war effort” such as radios, cameras, bicycles, electrical appliances, and other valuables, to local officials. In September 1941, a decree prohibited Jews from using public transportation. In the same month came the notorious edict requiring Jews over the age of six to wear the yellow Jewish Star (Magen David) on their outermost garment. While ghettos were generally not established in Germany, strict residence regulations forced Jews to live in designated areas of German cities, concentrating them in “Jewish houses” (“Judenhäuser”). German authorities issued ordinances requiring Jews fit for work to perform compulsory forced labor.

In early 1943, as German authorities implemented the last major deportations of German Jews to Theresienstadt or Auschwitz, German justice authorities enacted a mass of laws and ordinances legitimizing the Reich's seizure of their remaining property and regulating its distribution among the German population. The persecution of Jews by legal decree ended with a July 1943 ordinance removing Jews entirely from the protection of German law and placing them under the direct jurisdiction of the Reich Security Main Office (Reichssicherheitshauuptamt-RSHA).

Public imagination associates the deportation of Jewish citizens with the “Final Solution,” but indeed the first deportations of Jews from the Reich—albeit Jews from areas recently annexed by Germany—began in October 1939 as part of the Nisko, or Lublin, Plan. This deportation strategy envisioned a Jewish “reservation” in the Lublin District of the Government General (that part of German-occupied Poland not directly annexed to the Reich). Adolf Eichmann, the German RSHA official who would later organize the deportation of so many of Europe's Jewish communities to ghettos and killing centers, coordinated the transfer of some 3,500 Jews from Moravia in the former Czechoslovakia, from Katowice (then Kattowitz) in German-annexed Silesia, and from the Austrian capital, Vienna, to Nisko on the San River. Although problems with the deportation effort and a change in German policy put an end to these deportations, Eichmann's superiors in the RSHA were sufficiently satisfied with his initiative to ensure that he would play a role in future deportation proceedings.

In addition, RSHA officials coordinated the deportation of approximately 100,000 Jews from German-annexed Polish territory (the so-called province of Danzig-West Prussia, District Wartheland, and East Upper Silesia) into the Government General in the autumn and winter of 1939–1940. In October 1940, Gauleiter Josef Bürckel ordered the expulsion of nearly 7,000 Jews from Baden and the Saarpfalz in southwestern Germany to areas of unoccupied France in a second deportation of German Jews. French authorities quickly absorbed most of these German Jews in the Gurs internment camp in the Pyrenees of southwestern France.

Upon Hitler's authorization, German authorities began systematic deportations of Jews from Germany in October 1941, even before the SS and police established killing centers (“extermination camps”) in German-controlled Poland. Pursuant to the Eleventh Decree of Germany's Reich Citizenship Law (November 1941), German Jews “deported to the East” suffered automatic confiscation of their property upon crossing the Reich frontier.

Between October and December 1941, German authorities deported around 42,000 Jews from the so-called Greater German Reich—including Austria and the annexed Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia—virtually all to ghettos in Lodz, Minsk, Kovno (Kaunas, Kovne), and Riga. German Jews sent to Lodz in 1941 and to Warsaw, the Izbica and Piaski transit ghettos and other locations in the Generalgouvernement in the first half of 1942 numbered among those deported together with Polish Jews to the killing centers of Chelmno (Kulmhof), Treblinka, and Belzec.

German authorities deported more than 50,000 Jews from the so-called Greater German Reich to ghettos in the Baltic states and Belorussia (today Belarus) between early November 1941 and late October 1942. There the SS and police shot the overwhelming majority of them. After selecting a small minority to survive temporarily for exploitation as forced laborers, the SS and police interned them in special German sections of the Baltic and Belorussian ghettos, segregated from those few local Jews whose survival the SS and police had permitted, generally to exploit special occupational skills.

Such “German ghettos” within a larger ghetto framework existed notably in Riga and in Minsk. SS and police officials killed most of these German Jews when they liquidated the ghettos in 1943. After late October 1942, the German authorities deported the majority of Jews remaining in Germany directly to the killing center at Auschwitz-Birkenau or to Theresienstadt.

German regulations initially exempted German Jewish war veterans and elderly persons over the age of sixty-five, as well as Jews living in mixed marriages (“privileged marriages”) with German “Aryans” and the offspring of those marriages from anti-Jewish measures, including deportations. In the end, German officials deported disabled and highly decorated Jewish war veterans as well as elderly or prominent Jews from so-called Greater German Reich and the German-occupied Netherlands to the Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto near Prague. Although the SS used the ghetto as a showcase to portray the fiction of “humane” treatment of Jews, Theresienstadt in actuality represented a way station for most Jews en route to their deportation “to the east.” The SS and police routinely relocated Jews from Theresienstadt, including German Jews, to killing centers and killing sites in German-occupied Poland, Belorussia, and the Baltic States. More than 30,000 died in the Theresienstadt ghetto itself, mostly from starvation, illness, or maltreatment.

In May 1943, Nazi German authorities reported that the Reich was judenrein (“free of Jews”). By this time, mass deportations had left fewer than 20,000 Jews in Germany. Some survived because they were married to non-Jews or because race laws classified them as Mischlinge (of mixed ancestry, or part Jewish) and were thus temporarily exempt from deportation. Others, called “U-Boats” or “submarines,” lived in hiding and evaded arrest and deportation, often with the aid of non-Jewish Germans who sympathized with their plight.

In all, the Germans and their collaborators killed between 160,000 and 180,000 German Jews in the Holocaust, including most of those Jews deported out of Germany.

REPARATIONS AND RESTITUTION

From: Shoah Resource Centre for more detail

Financial compensation for Jewish suffering during the Holocaust and reimbursement for Jewish property that was stolen by the Nazis. From 1953 to 1965, West Germany paid the State of Israel, Jewish survivors, and German refugees hundreds of millions of dollars in a symbolic attempt to make up for the crimes committed by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

TODAY

From: ‘In Germany, a Jewish community now thrives’ By Mike Ross, The Boston Globe November 02, 2014

Since first arriving in what would become Germany more than 1,800 years ago, Jews have searched for acceptance. No matter how desperate their attempts to demonstrate their standing as good German citizens — in some cases converting to Christianity, enlisting to fight in World War I, even trying to persuade their American counterparts to be less critical of the rising new leader Adolf Hitler — nothing brought them acceptance by their countrymen.

That, however, may be changing. Seventy years after the Holocaust, as anti-Semitism churns across Europe, the Jewish population on the continent is plummeting to record lows. New strands of hatred foment seemingly justified by the policies of Israel — a sovereign country thousands of miles away. And yet Germany has suddenly reemerged as a home for Jews.

Ask Cilly Kugelmann, the vice director of the Jewish Museum Berlin. Kugelmann is the daughter of two Polish Holocaust survivors who, as it is said, “grew up sitting on packed suitcases.” Today, she says she can’t think of anywhere else she’d rather live than Germany. “Germany is one of the safest places for Jews worldwide,” Kugelmann said.

In preparing to visit Germany for the first time, nothing was further from my own beliefs. In the place where my father’s family was slaughtered, I assumed that no Jew would ever again see Germany as their home. How could they?

After all, a walk down a narrow Berlin street takes one to where the city’s Jewish population was routinely rounded up to be sent to concentration camps — and to the windows of homes filled with complicit onlookers. Nazis used the familiar settings of a Jewish school and community center to lull their victims into a false sense of security, even though by then, many knew they were being sent to their deaths. German residents knew full well the fate of their Jewish neighbors — this street was commonly referred to as “Todes Straße” or “Death Street.”

After the war, the once thriving Jewish community of Berlin, which at its high point reached 180,000, was left with only 7,000. In East Berlin — the section controlled by the former Soviet Union — its population was down to several hundred and predicted to reach zero in a matter of years.

In the late 1960s my father returned to Germany to visit for the first time since being liberated by American soldiers. Despite the celebrated triumphs of Simon Wiesenthal the Nazi hunter, and the prosecutions that were the result of the Nuremberg trials, he found his homeland awash in Nazis, many of whom were back in positions of power in government. When an attempt was made to finally prosecute high-ranking Nazis residing in Germany, it failed miserably. Of 400 perpetrators who were prosecuted, 13 would be convicted, and only six would go to jail.

As the civil rights era drew to a close in the United States, a movement of German students, known as the 68ers, was just beginning. These young people demanded answers from their parents and grandparents.

It took the next generation to demand change. As the civil rights era drew to a close in the United States, a movement of German students, known as the 68ers, was just beginning. These young people demanded answers from their parents and grandparents — generations who started two world wars and were responsible for humankind’s greatest atrocities.

Gradually, Germany began to confront its past. Public schools were required to teach about the Holocaust and make mandated visits to former concentration camps. Reparation payments were made to victims, and laws were enacted to make it a crime to deny the Holocaust or to display Nazi symbols. Immigration laws were finally liberalized to no longer require German blood as a precondition to becoming a citizen.

The Germany of today is a different place, particularly in Berlin, where 45,000 Jewish residents now live. Waves of immigrants have arrived every decade since the war ended. Most recently large numbers of young Israelis are moving here, attracted by arts, culture, and a more reasonable cost of living. Ironically they live quite peaceably in the same emerging neighborhoods as young Muslim emigres. And for the first time since the war, German-speaking rabbis are being trained in seminaries.

Two years ago, one of those rabbis, Daniel Alter, was viciously attacked in front of his 7-year-old daughter as he prepared for the Jewish High Holy Days. I asked him if he believes that Jews will ever be home in Germany. He answered by saying, “My suitcase is definitely unpacked, but I know where it is.”

Today the gilded dome of Berlin’s New Synagogue rises over the Spree River as a prominent landmark announcing that a Jewish community thrives. And it does. For now, it does.

HOW DO MODERN DAY GERMANS FEEL ABOUT THE JEWS?

Go to Quora

GERMAN HOLOCAUST MEMORIALS

From: Holocaust Memorials in Germany (more detailed information by links from this site)

These Holocaust memorials, museums, and former concentration camps in Germany are dedicated to never forget the Holocaust and its millions of victims. All of the listed memorial sites offer tours, exhibitions, documentary films, or original camp buildings to educate visitors about the history and horrors of the Holocaust in Germany.

1. Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, in Berlin

The architect Peter Eisenmann designed Berlin's Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, which is laid out on a 4.7-acre site between Brandenburg Gate and Potsdamer Platz. The centerpiece of the sculpture is the “Field of Stelae”, covered with more than 2,500 geometrically arranged concrete pillars. You can enter and walk through the unevenly sloping field from all four sides. The strong columns, all slightly different in size, evoke a disorienting, wave-like feeling that you can only experience when you make your way through this gray forest of concrete. The adjacent underground museum holds the names of all known Jewish Holocaust victims.

The concentration camp of Dachau, 10 miles northwest of Munich, was one of the first concentration camps in Nazi Germany and would serve as a model for all subsequent camps in the Third Reich. Dachau visitors of the memorial site follow the "path of the prisoner", walking the same way prisoners were forced to after their arrival in the camp. You will see the original prisoner baths, barracks, courtyards, and the crematorium, as well as an extensive exhibition and various memorials.

The Jewish Museum Berlin is not only a holocaust museum – its historic exhibition chronicles "Two Millennia of German Jewish History" and documents Jewish life in Germany from Roman Times to present day. But the striking architecture of Daniel Libeskind’s building makes palpable the feelings of those who were exiled and lost: The shape of the museum is reminiscent of a shattered Star of David, irregularly shaped windows are cut into the steel-clad facade, bizarre angles, and ‘voids’ stretch the full height of the building. The Holocaust Tower and the art installation “Fallen Leaves” are just another moving and unique experience.

4. Concentration Camp Sachsenhausen

About 30 minutes north of Berlin lies the memorial site Sachsenhausen, a former concentration camp in Oranienburg. The camp was erected in 1936, and until 1945, more than 200,000 people were imprisoned here by the Nazis. Sachsenhausen was in many ways one of the most important concentration camps in the Third Reich: It was the first camp established under Heinrich Himmler as Chief of the German Police and its architectural lay-out was used as a model for almost all concentration camps in Nazi Germany. After the camp was liberated on April 22, 1945 by Soviet and Polish troops, the Soviets used the site and its structures as an interment camp for political prisoners from fall of 1945 to 1950.

5. Concentration Camp Buchenwald

More than 250,000 people from 50 nations were imprisoned in the former camp Buchenwald, close to the city of Weimar; the memorial site houses various exhibitions and you can also see the former grounds of the camp, the gatehouse and detention cells, watchtowers, the crematorium, the disinfection centre, the railway station, SS quarters, the quarry and graveyards. There are signposted walks throughout the extensive site, including the routes taken by the former patrols.

6. Concentration Camp Bergen Belsen

Along with the death camp in Auschwitz, Bergen Belsen in Lower Saxony became an international symbol for the horrors of the Holocaust. Anne Frank was imprisoned in this camp and died of Typhus in March of 1945. Today, the grounds of the former concentration camp are a cemetery with various sculptures commemorating the ones who suffered and died at Bergen Belsen. There is also a newly opened Documentation Center, which houses all documents, photographs, and films exploring the history of the camp.

7. Concentration Camp Flossenbürg

The concentration camp Flossenbürg, built in 1938, is located in the Upper Palatinate region in Bavaria. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, an influential German pastor and theologist, was imprisoned here and died only 23 days before Flossenbürg was liberated in April 1945. The Memorial offers a guided tour in English, which includes parts of the historic exhibition "Flossenbürg Concentration Camp, 1938-1945".

8. Neuengamme Concentration Camp Hamburg

The Neuengamme concentration Camp, which was housed in a former brick factory in the outskirts of Hamburg, was the largest camp in the North of Germany, comprising of 80 satellite camps between 1938 and 1945. In May 2005, on the 60th anniversary of the camp’s liberation, a redesigned memorial site was opened, including several exhibitions that document the history of the site and remember the suffering of over 100,000 people imprisoned here. Fifteen historic concentration camp buildings on the site are preserved.

European Holocaust Memorials,

Information Portal to European Sites of Remembrance.

The Nazi Totalitarian Regime Schools History

The German Occupation of Europe, Brief Year by Year Outline Holocaust Research Project

Anti-Semitism in History: Nazi Anti-Ssemitism

The Roots of Hitler's Murderous Anti-Semitism

Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprencticeship by Brigitte Hamann

Ten Responses to Jewish Lackeys

Germany: Jewish Population in 1933

German Jewish Refugees, 1933–1939

The Day Hitler Blinked Research in Review, by Barbara Ash

.For more information on this article, contact:

Dr. Nathan Stoltzfus: 850-644-9529; e-mail: [email protected]

Day and night for a week in early 1943, hundreds of unarmed German women did something that was unheard of in Nazi Germany.

They stood toe-to-toe with machine gun-wielding Gestapo agents and demanded the release of their Jewish husbands from Adolph Hitler’s murderous grip. The men were locked up in the Jewish community center in the heart of Berlin, victims of Hitler’s "final roundup" of German Jews.

The women's courage and passion prevailed: As thousands of other Berlin Jews were crammed into cattle cars and transported to Auschwitz, the Jews married to “Aryan” German women were set free.

German Unification |

3 Minute History

Jabzy (3.32)

German Unification

Dr. Michael Brooks

(27.41)

SUMMARY

_________________________

Germany consisted of many small states. The move towards unification gathered pace in the 19th century. Unification was achieved under the leadership of Prussia in 1871 (see videos below). This was the environment in which the Jews lived and eventually led to WW1, the rise of Hitler, WW2, the Holocaust, the subsequent recriminations and voluntary payment of restitution and reparations.

There were Jewish settlers from the early 5th century. During the Crusades entire communities were murdered. The following centuries were a mixture of peace and repression.

Jewish political emancipation in Europe began with Napoleon at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries with the concepts of liberty, fraternity and equality spreading into Central Europe. Many German states rescinded Jewish rights following the Congress of Vienna in 1814-1815.

In July 1869, the Prussian King Wilhelm I promulgated the North German Confederation Constitution. This gave Jews civil and political rights in twenty-two German states and was adopted by the new German empire in 1871.

Jewish emancipation led to many changes in Jewish and non-Jewish society.

The German Jews began their Reform Movement in the early 1800’s to maintain a connection to Judaism, while using the newly-won rights and freedoms available to a member of European society. This included major changes to what could be eaten (kashrut), shabbat observance and beliefs including the Divine origin of the Torah. (Note: The use of the term ‘Reform’ can be confusing as it differs between countries. For example the Reform movement in Britain did not evolve from German Reform Judaism but from a reformation and reaction to traditional practices.) (See Wikipedia).

The Reform service had a choir, robes, and an organ, was in German, instead of Hebrew, had German songs and prayers to emphasize nationalistic loyalty and make synagogue worship resemble the mainstream German Protestant service.

The Sabbath was changed from Saturday to the Christian Sunday, and synagogues were called "temples" to show they no longer looked to rebuilding "The Temple" in Jerusalem.

Traditional Jews were called ‘Orthodox’ implying they were a relic of the past, as opposed to ‘Reform’ who thought of themselves as forward thinking, modern and progressive. They rejected the idea of a Jewish nation, proclaiming themselves ‘Germans of the Mosaic faith’. They did not want to appear to be different or to have their loyalty questioned because of their allegiance to another people. They opposed the idea of a return to Israel.

In WW1 100,000 German Jews enlisted. As conditions deteriorated, antisemitism flourished and they were accused of profiteering, avoiding military service and spying. Antisemitism flourished.

Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933. He believed that Germans were part of a race called ‘Aryans’ who were superior to all others and who would one day rule the world. As Jews were a separate race they could not be German but a group who conspired against Aryans to rule the world for themselves. ‘Purity of the Blood’ was one way in which this was expressed.

As some of the most prominent German communists had been Jewish, Hitler believed Jews had created communism to destroy the Aryans. His aim became to destroy communism and the Jews.

In 1938 Kristalnacht led to the destruction of Jewish shops and synagogues. In 1938-1939 10,000 children (Kindertransport) left Germany, without their parents, for resettlement elsewhere.

Following the outbreak of war on September 1, 1939, the government imposed new restrictions on Jews, the relinquishment of property “essential to the war effort” such as radios, cameras, bicycles, electrical appliances and strict food rationing. The first deportations of Jews from the Reich—albeit Jews from areas recently annexed by Germany—began in October 1939. In May 1943, Nazi German authorities reported that the Reich was judenrein (“free of Jews”). The Germans and their collaborators killed between 160,000 and 180,000 German Jews in the Holocaust, including most of the Jews deported from Germany.

Since the end of WW2 Germany has begun to confront its past. Public schools were required to teach about the Holocaust and make mandated visits to former concentration camps. Reparation payments were made to victims, and laws were enacted to make it a crime to deny the Holocaust or to display Nazi symbols. Immigration laws were liberalized to no longer require German blood as a precondition to citizenship.

The Germany of today is a different place, particularly in Berlin, where 45,000 Jews live. Immigrants have arrived every decade since the war ended. Many young Israelis have moved here. German-speaking rabbis are being trained.

Financial compensation has been made for Jewish suffering during the Holocaust and for property stolen by the Nazis.

Holocaust memorials, museums, and former concentration camps are dedicated to never forget the Holocaust and its millions of victims. All of the listed memorial sites offer tours, exhibitions, documentary films, or original camp buildings to educate visitors about the history and horrors of the Holocaust in Germany.

Jewish Emigration from Germany

1933 to 1938

UNEXPLAINED MYSTERIES:

The Mind of Adolf Hitler

Documentary Tube (50.24)

INSIDE THE MIND OF ADOLF HITLER

Documentary List

BBC Discovery (46.55)

THE WAR THAT MADE THE NAZIS

Dr Alan Brown (48.29)

|

CLICK BUTTON TO GO TO SECTION |

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

THE JEWS OF GERMANY