|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CLICK BUTTON |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THE INQUISITION AND THE |

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

THE INQUISITIONS LASTED FOR ALMOST 600 YEARS

The Medieval Inquisition was a series of Inquisitions (Catholic Church bodies charged with suppressing heresy) from around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). The Medieval Inquisition was established in response to movements considered apostate or heretical to Christianity, in particular Catharism and Waldensians in Southern France and Northern Italy.

The Spanish Inquisition was authorized by Pope Sixtus IV in 1478 at the request of King Ferdinand V and Queen Isabella. Sixtus also agreed its independence. The wars of independence of the former Spanish colonies in the Americas concluded with the abolition of the Inquisition in every quarter of Hispanic America between 1813 and 1825.

The last execution of the Inquisition was in Spain in 1826, the execution by garroting of the school teacher Cayetano Ripoll for purportedly teaching Deism in his school.

It was permanently suppressed by decree on July 15, 1834.

The Portuguese Inquisition was authorised in 1536 and abolished in 1821. in the wake of the Liberal Revolution of 1820, the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese Nation" abolished the Portuguese inquisition in 1821.

The Roman Inquisition in the Papal States was from 1542. After the restoration of the Pope as the ruler of the Papal States in 1814. Its last arrest was in 1858 of a six year old Jewish boy called Edgar Mortaro. in Bologna

The Inquisition had lasted for about 600 years

In 1908 the name of the Congregation became

"The Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office".

Then in 1965 to "Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith"

_____________________________________

To understand how the Inquisition worked and the fear it caused read

Richard Zimler on the Goa Inquisition ,

‘The Saintly Men of Safed’ in ‘The Source ‘ by James Michener

and ‘Cathedral of the Sea’ by Ildefonso Falcones.

THE MEDIEVAL INQUISITION

New World Encyclopedia

The Medieval Inquisition is a term historians use to describe the various inquisitions that started around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisition (1184-1230s) and later the Papal Inquisition (1230s). It was in response to large popular movements throughout Europe considered apostate or heretical to Christianity, in particular the Cathars and Waldensians in southern France and northern Italy. These were the first inquisition movements of many that would follow. Just as Constantine assumed that his Empire needed one Church, with one creed to unify his subjects, so the Medieval world thought that conformity to the teachings of the Church was necessary in order to maintain the social fabric. The Church was fully integrated into the social system. No king could ascend his throne without the Church's blessing. Bishops and Abbots were also feudal lords, with serfs subject to their authority, and acted as royal advisers alongside the nobles. Kings were understood to be divinely anointed, like the Biblical David. To dissent from the teachings of the Church—or even to cease to worship in the Church—was regarded as undermining its authority. If the authority of the church was undermined, so was that of the king and his assistants. People who were considered heretics often questioned whether they needed the services of priests. They were also often critical of the wealth of the clergy, pointing out that Jesus had been poor. At bottom, a concern for the preservation of the social order informed the Inquisition. The secular rulers thought that if the authority of the Church was questioned, the basis of their own authority and rights would be undermined and anarchy would ensue.

The Inquisition was created through papal bull, Ad Abolendam, issued at the end of the 12th century by Pope Lucius III to combat the Albigensian heresy in southern France. There were a large number of tribunals of the Papal Inquisition in various European kingdoms during the Middle Ages through different diplomatic and political means. In the Kingdom of Aragon, a tribunal of the Papal Inquisition was established by the statute of Excommunicamus of Pope Gregory IX, in 1232, during the era of the Albigensian heresy, as a condition for peace with Aragon. The Inquisition was ill-received by the Aragonese, which led to prohibitions against insults or attacks on it. Rome was particularly concerned about the 'heretical' influence of the Iberian peninsula's large Muslim and Jewish population on the Catholic. It pressed the kingdoms to accept the Papal Inquisition after Aragon. Navarra conceded in the 13th century and Portugal by the end of the 14th, however its 'Roman Inquisition' was famously inactive. Castile refused steadily, trusting on its prominent position in Europe and its military power to keep the Pope's interventionism in check. By the end of the Middle Ages, England, due to distance and voluntary compliance, and Castile (future part of Spain) due to resistance and power, were the only Western European kingdoms to successfully resist the establishment of the Inquisition in their realms.

THE SPANISH INQUISITION

New World Encyclopedia

The Spanish Inquisition was set up by King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile in 1478, with the approval of Pope Sixtus IV. In contrast to the previous Inquisition, it operated completely under royal authority, though staffed by secular clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy See. It aimed primarily at converts from Judaism and Islam (who were still residing in Spain after the end of the Moor control of Spain), who were suspected of either continuing to adhere to their old religion (often after having been converted under duress) or having fallen back into it, and later at Protestants; in Sicily and Southern Italy, which were under Spanish rule, it targeted Greek Orthodox Christians. After religious disputes waned in the seventeenth century, the Spanish Inquisition more and more developed into a secret police against internal threats to the state.

The Spanish Inquisition would subsequently be employed in certain Spanish colonies, such as Peru and Mexico. The Spanish Inquisition continued in the Americas until Mexican Independence and was not abolished in Europe until 1834.

One source estimates that as many as 60 million Native Americans were killed during the Spanish Inquisition, some of whom were already Christians. Most experts reject this number. Estimates of how many people were living in the Americas when Columbus arrived have varied tremendously; twentieth century scholarly estimates ranged from a low of 8.4 million to a high of 112.5 million persons. Given the fragmentary nature of the evidence, precise pre-Columbian population figures are impossible to obtain, and estimates are often produced by extrapolation from comparatively small bits of data. In 1976, geographer William Denevan used these various estimates to derive a "consensus count" of about 54 million people, although some recent estimates are lower than that.

CREATION OF THE SPANISH INQUISITION

There are several hypotheses of what prompted the creation of the tribunal after centuries of tolerance (within the context of medieval Europe). The truth is probably a combination of varieties of them. (Go to Wikipedia for more detail about the hypotheses below)

The "Too Multi-Religious" hypothesis

The Spanish Inquisition (Inquisición Española) can be interpreted as a response to the multi-religious nature of Spanish society following the reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslim Moors. After invading in 711, large areas of the Iberian Peninsula were ruled by Muslims until 1250, when they were restricted to Granada, which fell in 1492. However, the Reconquista did not result in the total expulsion of Muslims from Spain, since they, along with Jews, were tolerated by the ruling Christian elite. Large cities, especially Seville, Valladolid and Barcelona, had significant Jewish populations centered in Juderia, but in the coming years, the Muslims were increasingly alienated and relegated from power centers.

The "Enforcement Across Borders" hypothesis

According to this hypothesis, the Inquisition was created to standardize the variety of laws and many jurisdictions Spain was divided into. It would be an administrative program analogous to the Santa Hermandad (the "Holy Brotherhood", a law enforcement body, answering to the crown, that prosecuted thieves and criminals across counties in a way local county authorities could not, ancestor to the Guardia Civil), an institution that would guarantee uniform prosecution of crimes against royal laws across all local jurisdictions.

The "Placate Europe" hypothesis

At a time in which most of Europe had already expelled the Jews from the Christian kingdoms the "dirty blood" of Spaniards was met with open suspicion and contempt by the rest of Europe. As the world became smaller and foreign relations became more relevant to stay in power this foreign image of "being the seed of jews and moors" may have become a problem.

The "Ottoman Scare" hypothesis

No matter if any of the previous hypotheses were already operating in the minds of the monarchs, the alleged discovery of Morisco plots to support a possible Ottoman invasion were crucial factors in their decision to create the Inquisition.

Philosophical and Religious Reasons

The creation of the Spanish Inquisition would be consistent with the most important political philosophers of the Florentine School, with whom the kings were known to have contact

The "Keeping the Pope in Check" hypothesis

The hierarchy of the Catholic Church had made many attempts during the Middle Ages to take over Christian Spain politically, such as claiming the Church's ownership over all land reconquered from non-Christians (a claim that was rejected by Castille but accepted by Aragon and Portugal).

Other hypotheses

Other hypotheses that circulate regarding the Spanish Inquisition's creation include:

- Economic reasons

- Intolerance and racism:

- Purely religious reasons

King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile set up the Spanish Inquisition in 1478. In contrast to the previous inquisitions, it operated completely under royal authority, though staffed by secular clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy See. It operated in Spain and in all Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Spanish Netherlands, the Kingdom of Naples, and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. It targeted primarily converts from Judaism (Conversos and Marranos) and from Islam (Moriscos or secret Moors) — both groups still resided in Spain after the end of the Islamic control of Spain — who came under suspicion of either continuing to adhere to their old religion or of having fallen back into it. Somewhat later the Spanish Inquisition took an interest in Protestants of virtually any sect, notably in the Spanish Netherlands. In the Spanish possessions of the Kingdom of Sicily and the Kingdom of Naples in southern Italy, which formed part of the Spanish Crown's hereditary possessions, it also targeted Greek Orthodox Christians. The Spanish Inquisition, tied to the authority of the Spanish Crown, also examined political cases.

In the Americas, King Philip II set up two tribunals (each formally titled Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición) in 1569, one in Mexico and the other in Peru. The Mexican office administered Mexico (central and southeastern Mexico), Nueva Galicia (northern and western Mexico), the Audiencias of Guatemala (Guatemala, Chiapas, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica), and the Spanish East Indies. The Peruvian Inquisition, based in Lima, administered all the Spanish territories in South America and Panama. From 1610 a new Inquisition seat established in Cartagena (Colombia) administered much of the Spanish Caribbean in addition to Panama and northern South America.

The Inquisition continued to function in North America until the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821). In South America Simón Bolívar abolished the Inquisition; in Spain itself the institution survived until 1834.

The period 1569–1621 also witnessed a series of controversial trials such as that of the Archbishop of Toledo and Primate of Spain, Bartolomé de Carranza (1503–1576) who spent many years in jail.

Juan Antonio Llorente the General Secretary of the Inquisition in Madrid from 1789 to 1814 had access to Inquisition archives. He wrote his great work ‘The History of the Inquisition of Spain, from the Time of its Establishment to the Reign of Ferdinand VI’ which was published in Paris in 1817/18. In this he estimated that 31,912 people were executed between 1480-1808.

Cases in the Spanish Inquisition, 1540–1700

(Excludes the tribunals of Cuenca, Cerdaña, and Palermo)

Judaizers Moriscos Protestants All Others Total Total Relaxed

4,397 10,817 3,646 25,814 44,674 1,604

9.8% 23.2% 8.1% 57.8% 100.0% 3.5%

Adapted from Jaime Contreras and Gustav Henningsen,

"Forty-four Thousand Cases of the Spanish Inquisition (1540–1700):

Analysis of a Historical Data Bank," in Henningsen and Tedeschi, 116.

Included in the category "All Others"

are propositions and blasphemy (27.1%),

bigamy and solicitation (8.4%),

acts against the Inquisition (7.5%),

superstition (7.9%), and various (6.8%).

The "Total Relaxed" involves only those sentenced to death in person.

The period 1569–1621 also witnessed a series of controversial trials such as the Archbishop of Toledo and Primate of Spain, Bartolomé de Carranza (1503–1576)

The Inquisition was not merely an expression of religious authority nor was it solely an instrument of social and political control....it was an arena where social and political cultures met and clashed on both shores of the Atlantic..... Persecuted groups whether Christianized Jews in Spain or native folk healers in the New World, were able to survive the Inquisition by strategies as diverse as preserving their experiences through literature and answering the need for medical care (From frontispiece Cultural encounters: the impact of the Inquisition in Spain and the New World, Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, UCLA, Perry, 1992)

See also World History in Context

PORTUGUESE INQUISITION

Wikipedia,

The Portuguese Inquisition (Portuguese: Inquisição Portuguesa), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of its king, John III. Manuel I had asked for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515 to fulfill the commitment of marriage with Maria of Aragon, but it was only after his death that Pope Paul III acquiesced. In the period after the Medieval Inquisition, it was one of three different manifestations of the wider Christian Inquisition along with the Spanish Inquisition and Roman Inquisition.

The major target of the Portuguese Inquisition were those who had converted from Judaism to Catholicism, the Conversos, also known as New Christians, Conversos or Marranos, who were suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. Many of these were originally Spanish Jews who had left Spain for Portugal, when Spain forced Jews to convert to Christianity or leave. The number of victims is estimated as around 40,000.

As in Spain, the Inquisition was subject to the authority of the King. It was headed by a Grand Inquisitor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the king, always from within the royal family. The Grand Inquisitor would later nominate other inquisitors. In Portugal, the first Grand Inquisitor was D. Diogo da Silva, personal confessor of King John III and Bishop of Ceuta. He was followed by Cardinal Henry, brother of John III, who would later become king. There were Courts of the Inquisition in Lisbon, Coimbra, and Évora, and for a short time (1541 until c. 1547) also in Porto, Tomar, and Lamego.

It held its first auto-da-fé in Portugal in 1540. Like the Spanish Inquisition, it concentrated its efforts on rooting out those who had converted from other faiths (overwhelmingly Judaism) but did not adhere to the strictures of Catholic orthodoxy.

The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to Portugal's colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa, where it continued investigating and trying cases based on supposed breaches of orthodox Roman Catholicism until 1821.

King João III: although it was his father and antecessor, king Manuel I (1495-1521), who had requested it, it was under John III that the Inquisition was established in Portugal.

Under John III, the activity of the courts was extended to the censure of books, as well as undertaking cases of divination, witchcraft, and bigamy. Originally aimed at religious matters, the Inquisition had an influence on almost every aspect of Portuguese life – political, cultural, and social.

In Portuguese India, the Goa Inquisition also turned its attention to Indian converts from Hinduism or Islam who were thought to have returned to their original ways. In addition, it prosecuted Hindus and Muslims (non-converts) who broke prohibitions against the observance of Hindu or Muslim rites or interfered with Portuguese attempts to forcibly convert non-Christians to Catholicism. Hundreds of thousands of Hindus were forced to move out of Goa if they did not convert. It was established in Goa in 1560 by Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques, who occupied the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan. The ancient Christian community of Malabar Nasranis on the south Indian coast was also persecuted in the Portuguese Inquisition. The Portuguese described the Malabar Nasranis as Sabbath-keeping Judaizers and burnt their Syriac-Aramaic manuscripts at the Synod of Diamper.

Among the main targets of the Inquisition were also the Portuguese Christian traditions and movements that were not perceived as orthodox. The millenarian and national Feast of the Cult of the Empire of the Holy Spirit, dating from the mid 13th century, spread throughout all mainland Portugal from then into the 14th century. In the following centuries it spread throughout Portugal's Atlantic islands and empire, where it was the main target of prohibition and surveillance by the Inquisition after the 1540s, since it had almost disappeared from continental Portugal and India. This spiritual tradition, practiced exclusively by non-religious officials and popular Brotherhoods in the Middle Ages and following centuries, was gradually restored only after the second half of the 20th century in some municipalities of mainland Portugal. By then, except for a few faithful and accurate local traditions, it had undergone major deletions and changes (in what remained or was restored) of the ancient rituals.

According to the traditional Feast of the Empire of the Holy Spirit, celebrated at the feast of Pentecost, a future, third age would be governed by the Empire of Holy Spirit and would represent a monastic or fraternal governance, in which the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, the intermediaries, and the organized Churches would be unnecessary, and infidels would unite with Christians by free will. Until the 16th century, this was the main annual festivity in most of the major Portuguese cities, with multiple celebrations in Lisbon, Porto, and Coimbra (3). The Church and the Inquisition would not tolerate a spiritual tradition entirely popular and without the mediation of the clergy at the time, and most importantly, celebrating a future Age which would bring an end to the Church.

The cult of the Holy Spirit survived in the Azores Islands among the local population and under the traditional protection of the Order of Christ. Here the arm of the Inquisition did not effectively extend its power, despite reports from local ecclesiastical authorities. Beyond the Azores, the cult survived in many parts of Brazil (where it was established in the 16th through 18th centuries) and is celebrated today in all Brazilian states except two, as well as in pockets of Portuguese settlers in North America (Canada and USA), mainly among those of Azorian descent.

The movements and concepts of Sebastianism and of the Fifth Empire were sometimes also targets of the Inquisition (the most intense persecution of Sebastianists being during the Philippine Dynasty, though it lasted beyond then), both considered unorthodox and even heretical. But targeting was intermittent and selective since some important familiares (associated people) of the Holy Office (Inquisition) were Sebastianists.

The financial problems of King Sebastian in 1577 led him, in exchange for a large sum of money, to allow the free departure of New Christians, and to ban the confiscation of property by the Inquisition for 10 years.

King John IV, in 1649, banned the confiscation of property by the Inquisition and was excommunicated immediately by Rome. This law was only fully withdrawn around 1656, with the death of the king.

From 1674 to 1681 the Inquisition was suspended in Portugal: autos-da-fé were suspended and inquisitors were instructed not to inflict sentences of relaxation, confiscation, or perpetual galleys. This was an action of António Vieira (see Encyclopedia.com) in Rome to put an end to the Inquisition in Portugal and its Empire. Vieira had earned the name of the Apostle of Brazil. At the request of the pope he drew up a report of two hundred pages on the Inquisition in Portugal, with the result that after a judicial inquiry Pope Innocent XI himself suspended it for five years (1676–81).

António Vieira had long regarded the New Christians with compassion and had urged King John IV, with whom he had much influence and support, not only to abolish confiscation but to remove the distinctions between them and the Old Christians. He had made enemies and the Inquisition readily undertook his punishment. His writings in favor of the oppressed were condemned as "rash, scandalous, erroneous, savoring of heresy, and well adapted to pervert the ignorant." After three years of incarceration, he was penanced in the audience-chamber of Coimbra on 23 December 1667. His sympathy for the victims of the Holy Office was sharpened by his experience of its "unwholesome prisons", where he wrote that "five unfortunates were not uncommonly placed in a cell nine feet by eleven, where the only light came from a narrow opening near the ceiling, where the vessels were changed only once a week, and all spiritual consolation was denied." Then, in the safe refuge of Rome, he raised his voice for the relief of the oppressed, in numerous writings in which he characterized the "Holy Office of Portugal as a tribunal which served only to deprive men of their fortunes, their honor, and their lives, while unable to discriminate between guilt and innocence; it was known to be holy only in name, while its works were cruelty and injustice, unworthy of rational beings, although it was always proclaiming its superior piety."

In 1773 and 1774 Pombaline Reforms abolished autos-da-fé and ended the Limpeza de Sangue (blood cleansing) statutes and their discrimination against New Christians, the Jews and all their descendants who had converted to Christianity in order to escape the Portuguese Inquisition.

The Portuguese inquisition was terminated in 1821 by the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Assembly of the Portuguese Nation."

In 2007, the Portuguese Government initiated a project to make available online by 2010 a significant part of the archives of the Portuguese Inquisition currently deposited in the Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, the Portuguese National Archives.

In December 2008, the Jewish Historical Society of England (JHSE) published the Lists of the Portuguese Inquisition in two volumes: Volume I Lisbon 1540–1778; Volume II Évora 1542–1763 and Goa 1650–1653. The original manuscripts, assembled in 1784 and entitled Collecção das Noticias, were once in the Library of the Dukes of Palmela and are now in the library of the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. The texts are published in the original Portuguese, transcribed and indexed by Joy L. Oakley. They represent a unique picture of the whole range of the Inquisition's activities and a primary source for Jewish, Portuguese, and Brazilian historians and genealogists.

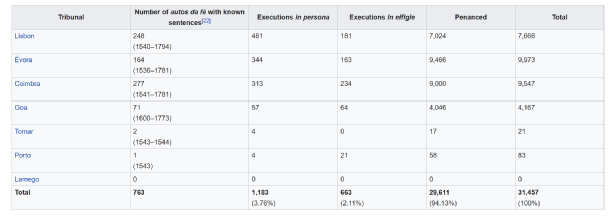

Table of Sentences

The archives of the Portuguese Inquisition are one of the best preserved judicial archives of early modern Europe (with notable exception of the Goa tribunal). Portuguese historian Fortunato de Almeida gives the following statistics of sentences pronounced in the public ceremonies autos da fe between 1536 and 1794

These statistics, although extensive, are not wholly complete, particularly in the case of Goa. The original documentation of this tribunal is almost entirely lost. A list of autos da fé in Goa presented by Almeida was compiled by the officials of the Inquisition in 1774, but is certainly only partial and does not cover the whole period of its activity. Some minor gaps concern also the remaining tribunals, i.e., there is no usable data about some fifteen autos da fé celebrated in Portugal between 1580 and 1640, while the records of short-lived tribunals in Lamego and Porto (both active from 1541 until c. 1547) are yet to be studied

POMBAL AND THE INQUISITION IN PORTUGAL

The Portuguese ruler began to curb

the most powerful arch-conservative force in the country on May 3rd, 1751

Richard Cavendish | Published in History Today Volume 51 Issue 5 May 2001

Sebastião de Carvalho, Marques de Pombal (1699-1782), was the virtual ruler of Portugal for more than a quarter of a century during the reign of King José I. A ruthless moderniser, he undoubtedly learned much from his previous seven-year stint in England as Portuguese ambassador to the court of George II. When he took control in Lisbon after José’s accession to the throne in 1750, Pombal set out to rein back the power of the landed aristocracy and build up Portuguese industry and commerce. To do this it was necessary to confront the Inquisition, the most powerful arch-conservative force in the country. In 1751 he made all sentences passed by the Inquisition subject to review by the crown, and so began to draw the institution’s teeth.

The Inquisition had been established in Portugal since 1547, on the Spanish model. Its apparatus of officials and informers, its courts and dungeons and torture chambers, its carefully stage-managed show trials and horrific burnings at the stake, inspired the same dread as the later secret police of totalitarian systems in Portugal and elsewhere. Its function was to wipe out religious dissent, but it was rootedly hostile to innovation of any kind and it was supported as an engine of conservatism by the landed aristocracy. The Inquisition bore especially hard on Jews, many of whom had been more or less forcibly converted as ‘New Christians’. It was also fiercely opposed to industrialisation and business, which it linked with ‘Jewish capital’, and many middle-class business people and traders fell into its claws.

Pombal gradually transformed the Inquisition by bringing it under state authority, virtually abolishing it as an engine of religious thought control and using it instead against those suspected of treason against the state. In 1769 he appointed his own brother, Paulo, a layman, as Inquisitor-General. Meanwhile, Pombal had been able to end the persecution of Portuguese citizens of Jewish descent and to abolish black slavery in Portugal – in both cases primarily for economic rather than humanitarian motives. He went on to crush the Jesuits, modernise Portuguese higher education, encourage the formation of strong trading companies to exploit the wealth of Brazil for Portugal’s benefit and build up Portugal’s commercial empire. At the same time he weakened the aristocracy, established an efficient state police force and created his own apparatus of terror. He made many enemies and when José I died in 1777, Pombal was immediately dismissed, subjected to long and brutal interrogation and banished to his country estate where he died in 1782.

ROMAN INQUISITION

Wikipedia

The Roman Inquisition, formally the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition, was a system of tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes relating to religious doctrine or alternate religious doctrine or alternate religious beliefs. In the period after the Medieval Inquisition, it was one of three different manifestations of the wider Catholic Inquisition along with the Spanish Inquisition and Portuguese Inquisition.

OBJECTIVES

Like other iterations of the Inquisition, the Roman Inquisition was responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of committing offenses relating to heresy, including Protestantism, sorcery, immorality, blasphemy, Judaizing and witchcraft, as well as for censorship of printed literature. After 1567, with the execution of Pietro Carnesecchi, an allegedly leading heretic, the Holy Office moved to broaden concerns beyond that of theological matters, such as love magic, witchcraft, superstitions, and cultural morality. However, the treatment was more disciplinary than punitive. The tribunals of the Roman Inquisition covered most of the Italian peninsula as well as Malta and also existed in isolated pockets of papal jurisdiction in other parts of Europe, including Avignon, a papal enclave within the territory of France. The Roman Inquisition, though, was considerably more bureaucratic and focused on pre-emptive control in addition to the reactive judicial prosecution experienced under other iterations.

FUNCTION

Typically, the pope appointed one cardinal to preside over meetings of the Congregation. Though often referred to in historical literature as Grand Inquisitors, the role was substantially different from the formally appointed Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition. There were usually ten other cardinals who were members of the Congregation, as well as a prelate and two assistants all chosen from the Dominican Order. The Holy Office also had an international group of consultants; experienced scholars of theology and canon law who advised on specific questions. The congregation, in turn, presided over the activity of local tribunals.

HISTORY

The Roman Inquisition began in 1542 as part of the Catholic Church's Counter-Reformation against the spread of Protestantism, but it represented a less harsh affair than the previously established Spanish Inquisition. In 1588, Pope Sixtus V established 15 congregations of the Roman Curia of which the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition was one. In 1908, the congregation was renamed the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office and in 1965 it was renamed again and is now known as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

While the Roman Inquisition was originally designed to combat the spread of Protestantism in Italy, the institution outlived that original purpose and the system of tribunals lasted until the mid 18th century, when pre-unification Italian states began to suppress the local inquisitions, effectively eliminating the power of the church to prosecute heretical crimes.

LATER HISTORY

The last notable action of the Roman Inquisition occurred in 1858, in Bologna, Papal States, when Inquisition agents legally removed a 6-year-old Jewish boy, Edgardo Mortara, from his family. The local inquisitor had learned that the boy had been secretly baptized by his nursemaid when he was in danger of death. It was illegal for a Catholic child in the Papal States to be raised by Jews. Pope Pius IX raised the boy as a Catholic in Rome and he went on to become a priest. The boy's father, Momolo Mortara, spent years seeking help in all quarters, including internationally, to try to reclaim his son. These efforts availed him none at all. The case received international attention and fueled the anti-papal sentiments that helped the Italian nationalism movement and culminated in the 1870 Capture of Rome.

AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE SPANISH INQUISITION’S

MOTIVATIONS AND CONSEQUENCES

(INCLUDES PORTUGUESE AND ROMAN INQUISITIONS)

Jordi Vidal-Robert JOB MARKET PAPER, October 2011, Abstract∗

The motivations behind the Spanish Inquisition (1478-1834) have long intrigued historians. This paper explores the role of the Spanish Inquisition as a repressive tool of the Spanish Crown and provides evidence regarding the long-term effects of this institution. In particular, I explore the relationship between inquisitorial activity and war from both a theoretical and an empirical point of view. The government’s demand for social control/repression was greater in periods of war because war increased the likelihood of internal revolts. To minimize the threat of rebellion, the Inquisition conducted more trials when Spanish war activity was intense. However, once the costs of the repressive activities exceeded its benefits, the Inquisition decreased its level of repression. This behavior indicates an inverse-U relationship between inquisitorial and war intensity. To test the predictions of this framework, I assemble time series data for seven Spanish inquisitorial districts addressing the annual trials of the Inquisition and wars conducted by the Spanish Crown. I show that there is an inverse-U relationship between wars and inquisitorial activity. My results are robust to the inclusion of data on the severity of the weather (droughts) and to adjustments for spillover effects from districts other than the main district under analysis. Using a database of 35,000 trials of the Inquisition, I show that religious persecution was especially significant during early stages of the Inquisition, while repressive motivations better explain the behavior of this institution in later periods. With respect to the consequences of the Spanish Inquisition, I show that regions that were more affected by the Inquisition are associated with lower economic development.

PORTUGUESE INQUISITION

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of the King of Portugal, João III. Manuel I had asked Pope Leo X for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515, but only after his death (1521) did Pope Paul III agree. The Portuguese Inquisition targeted the Sephardic Jews, who had been forced to convert to Christianity. Most were those expelled by Spain in 1492 and ha moved to Portugal.

The Portuguese Inquisition came under the authority of the King. At its head stood a Grand Inquisitor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the Crown, and always from within the royal family. The Grand Inquisitor would later nominate other inquisitors. Cardinal Henry was the first Grand Inquisitor. Later he became King Henry of Portugal. Courts of the Inquisition operated in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra, and Évora.

The Portuguese Inquisition held its first auto-da-fé (the Portuguese equivalent of the Spanish auto de fé) in Portugal in 1540. It concentrated its efforts on rooting out converts from other faiths (overwhelmingly Judaism) who did not adhere to the observances of Catholic orthodoxy; the Portuguese inquisitors mostly targeted the Jewish "New Christians", conversos, or marranos.

The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations to Portugal's colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa, where it continued as a religious court, investigating and trying cases of breaches of the tenets of orthodox Roman Catholicism until 1821.

King João III (reigned 1521–1557) extended the activity of the courts to cover book-censorship, divination, witchcraft and bigamy Originally oriented for a religious action, the Inquisition had an influence in almost every aspect of Portuguese society: politically, culturally and socially.

According to Henry Charles Lea between 1540 and 1794 tribunals in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra and Évora resulted in the burning of 1,175 persons, the burning of another 633 in effigy, and the penancing of 29,590. But documentation of fifteen out of 689 Autos-da-fé has disappeared, so these numbers may slightly understate the activity.

The "General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese Nation" abolished the Portuguese inquisition in 1821.

GOA INQUISITION

The Portuguese started this Inquisition in their colony of Goa in 1560. Where it was primarily devoted to antisemitism and anti-Hinduism, Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques set it up in the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan.

Click here for more information.

MEASURING THE PORTUGUESE INQUISITION

University of Michigan-Dearborn R. Warren Anderson June 2013

(Introduction to 31 page paper) The Portuguese Inquisition lasted for centuries and predominantly sentenced New Christians (people of Jewish descent). A dataset of more than 26,000 of those sentenced was tested for factors that influenced inquisitorial severity. Increasing food prices positively influenced sentencing. Various political variables significantly determined inquisitorial activity, both positively and negatively. New Christian anti-inquisitorial lobbying was effective at lowering sentencing. Such influence on the inquisition by secular variables leads to the conclusion that the institution instituted to keep religion pure was not entirely about keeping religion pure, but is better understood as a bureaucratic entity

ROMAN INQUISITION

In 1542 Pope Paul III established the Congregation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition as a permanent congregation staffed with cardinals and other officials. It had the tasks of maintaining and defending the integrity of the faith and of examining and proscribing errors and false doctrines; it thus became the supervisory body of local Inquisitions. Arguably the most famous case tried by the Roman Inquisition involved Galileo Galilei in 1633.

The penances and sentences for those who confessed or were found guilty were pronounced together in a public ceremony at the end of all the processes. This was the sermo generalis or auto-da-fé. Penances might consist of a pilgrimage, a public scourging, a fine, or the wearing of a cross. The wearing of two tongues of red or other brightly colored cloth, sewn onto an outer garment in an x pattern, marked those who were under investigation. The penalties in serious cases were confiscation of property or imprisonment. The most severe penalty the inquisitors could themselves impose was life imprisonment. Thus, when the inquisitors handed a guilty person over to civil authorities, it was tantamount to a demand for that person's execution.

Following the French invasion of 1798, the new authorities sent 3,000 chests containing over 100,000 Inquisition documents to France from Rome (some were lost en route to France, others were used as scrap paper). After the restoration of the Pope as the ruler of the Papal States after 1814, Roman Inquisition activity continued until the mid-19th century.

INQUISITIONS IN THE AMERICAS

The Inquisition in the New World By Clara Steinberg-Spitz)

The Spaniards brought the Inquisition to the Americas and used it to punish the native inhabitants. Through the 1500's, 879 heresy trials were recorded in Mexico alone. Thus, other than people, the Inquisition was one of Europe's first exports to the Americas. Church leaders supported the suppression, enslavement and murder of native inhabitants - a 1493 papal Bull justified declaring war on all non-Christian natives in the Americas. Jurist Encisco wrote in 1509:

The king has every right to send his men to the Indies to demand their territory from these idolaters because he had received it from the Pope. If the Indians refuse, he may quite legally fight them, kill them and enslave them, just as Joshua enslaved the inhabitants of the country of Canaan.

According to Liebman, as early as 1508, bishops in Havana and Puerto Rico informed Madrid that the New World was being filled with hebreo cristianos (Hebrew Christians), nuevo cristianos (New Christians), conversos (converts), Moriscos (Moors), and other heretics, in spite of several decrees barring their entry. Silvio Zavala wrote: "The Holy Office in Spanish America persecuted the apostates, Moriscos, Jews, Protestants and, in general, heretics. It manifested in America the same intransigency that had characterized the religious life of the Peninsula since the beginning of the modern period." Due to the shortage of secular clergy in the New World, the pope issued the Bull Omnimoda in 1522, and granted special permission to the prelates of the monastic orders in the New World to perform, in the absence of bishops in the vicinity, all Episcopal functions except ordination. Torquemada's organizational and administrative abilities, and his zeal for the preservation of the faith set the course of the Spanish Inquisition for the 341 years of its existence. As the activities of the Holy Office expanded, it became necessary to establish branches throughout Spain and the New World with the Suprema as the head office. The need of a tribunal of the Holy Office in Mexico was expressed as early as 1532. In fact, the first auto de fé in Mexico was held in October 1528, with Fray Vicente de Santa Maria presiding. Two Jews were burned at the stake, and two others were reconciled. On January 25, 1569, Philip II decreed the establishment of the first two formal Dominican tribunals in the New World, one for New Spain (Mexico) and one for Peru. They were known by the full title of "El Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición". The Mexican branch included all of the audiencias of Mexico, Guatemala, New Galicia, and the Philippines. The tribunal at Cartagena was not established until 1610. Prior to that all prisoners south of New Spain were sent to Lima, Peru, for trial. The Cartagena tribunal had jurisdiction over a vast area, including the bishopries of Cartagena, Panama, Santa Marta, Puerto Rico, Popayan, Venezuela, and Santiago de Cuba. There were many Jews in Cartagena and its vicinity, and they were quite visible; but according to Seymour B. Liebman, the Holy Office was more involved in disputes among the inquisitors than in persecuting heretics and Jews. The sixty-three procesos of Jews before the tribunal in Cartagena indicate that all were born in Portugal; nine of them were tortured and only one was sentenced to serve in the galleys sailing between Puerto Bello and Spain. Even though the Holy Office was established in Portugal in 1536, there never was a tribunal in Portuguese Brazil. Brazilian prisoners were tried in Portugal. Each viceroyalty was expected to give the tribunals of the Holy Office complete cooperation. The tribunals were autonomous institutions independent of secular authority. The Holy Office was free of the control of the King.

How it worked is vividly illustrated by the story of the Family Carvajal

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

THE MEDIEVAL. SPANISH, PORTUGUESE

AND ROMAN INQUISITIONS