|

CLICK BUTTON TO GO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Videos |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

JUDENRÄTE (in plural, Judenraete OR Judenräte)

Yad Vashem

Jewish communities/camps councils within

Nazi-occupied Europe

To implement Nazi Jewish policies

These Jewish councils often performed a balancing act: on one hand, they felt a responsibility to help their fellow Jews as much as possible, on the other, they were supposed to carry out the orders of the Nazi authorities - often at the expense of their fellow Jews. The role played by the Judenraete is one of the most controversial aspects of the Holocaust period.

The Judenraete were not set up in a consistent manner. In some cases a Judenrat was responsible for one city only, while in other instances a Judenrat or a similar body held authority over an entire district. Sometimes jurisdiction was maintained over a whole country as in; Germany, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Slovakia, Romania, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

The first Judenraete were established in occupied Poland in the fall of 1939, just weeks after World War II broke out - on orders issued by Gestapo head Reinhard Heydrich and implemented by Generalgouvernement head Han Frank. Judenrat were to be comprised of "influential people and rabbis." Frank ordered that in areas with less than 10 000 Jews, the Judenrat would consist of 12 members, while in larger cities or towns the council would maintain of 24 members. The councils were to be elected by the local population and the council itself would elect its chairman and vice-chairman. The Germans then had to approve the selections. In certain cases, Jewish activists refused to participate in the Judenraete, as they suspected— correctly—how the Germans intended to exploit the councils, and that they would force them to act against their fellow Jews. However, in general, most Jewish leaders did join the Judenraete.

After the Judenraete were established, the Germans instructed them to carry out various administrative and economic measures that were destructive to the Jews. In most instances, the Judenraete tried to delay or lighten the measures. Other Judenraete members believed that if they would comply with the Germans' demands, then the Germans would see how productive the Jews could be, and ease the blows. In a few cases,

Judenraete members took advantage of their privileged positions for their personal gain - leading to much animosity and criticism on the part of the Jewish communities. The Judenraete were put in charge of; transferring Jews from their homes to Ghettos, maintaining the peace and preventing smuggling. In addition, they were responsible to hand out the meager food rations allowed by the Germans. In some cases, the Judenraete tried to alleviate the starvation in their ghettos by procuring food illegally. The councils also set up mutual help organizations, hospitals, medical clinics, and orphanages.

From 1940 the Judenraete were ordered to provide workers to do forced labor in labor camps. In most cases the councils complied with the Germans' demand, again causing tension in the community.

When the Nazis embarked upon the "final solution"—the annihilation of European Jewry—they demanded from many of the Judenraete that they hand over names of Jews to be deported to extermination camps. Each council had to decide whether and how much to comply with the Germans. Most looked for ways to prevent or at least decelerate the deportation process; some did so by adopting a policy of "rescue by labor." They tried to show the Germans that the Jews were vital to the war economy as producers of various important products and armaments, and that the Germans could not afford to exterminate them en mass. Some council leaders decided to sacrifice certain elements of the community for others—cutting off the hand to save the rest of the body. Both during and after the war, this practice provoked great criticism and controversy. In several cases Judenraete members planned and took part in armed resistance to the Nazis

JUDENRÄT

Encyclopedia Brittanica

Judenräte, ( German: Jewish Councils) Jewish councils established in German-occupied Poland and eastern Europe during World War II to implement German policies and maintain order in the ghettos to which the Nazis confined the country’s Jewish population. Reinhard Heydrich, chief of Nazi Germany’s Gestapo, established the Judenräte (singular: Judenrat) by decree on September 21, 1939, three weeks after the German invasion of Poland. No aspect of Jewish behaviour during the Holocaust was more controversial than the conduct of the Judenräte.

The Judenräte were composed of up to 24 Jewish men, chosen from “remaining authoritative personalities and rabbis.” When the Judenräte were first established, the Jews did not know the ultimate intensions of the Germans toward them nor, according to most scholars, were the intentions of the Germans yet clear. Jewish leaders assumed that their responsibility was to provide for the needs of Jews, who they assumed would remain in the ghetto indefinitely. The Judenräte became a municipal authority providing sanitation, education, commerce, and food for their increasingly beleaguered community. With meager resources at their disposal, they struggled to meet the basic needs of starving ghetto residents and to make life bearable. Their German oppressors provided the basis of their power. At first unaware of their people’s fate, in time they understood their role in maintaining communities destined for annihilation.

The Judenräte relied on forms of taxation to support their activities. Jewish police forces were established to enforce Judenräte decrees and provide order in the ghetto. The individual Judenräte used different models of governance. In Warsaw, the largest of the ghettos, laissez-faire capitalism was the rule under Judenrat chairman Adam Czerniaków. Private enterprise continued for as long as possible. In Łódź, under the chairmanship of Mordecai Chaim Rumkowski, authority was more centralized. Commerce, trade, and all municipal services, including the distribution of food and housing, were tightly controlled.

The level and tenor of interaction between the Judenräte and the Germans differed ghetto by ghetto, leader by leader, and meeting by meeting. Some meetings with Nazi officials were courteous and might even appear friendly, others were harsh and threatening. Generally, the Germans would make demands of the Judenräte, who, in return, would beg for supplies and relief on behalf of their beleaguered populations.

Among the ghetto residents, the Judenräte often drew anger. Many viewed their role in enforcing German decrees and conditions as indistinguishable from the role of the Germans who had ordered them. This anger grew when conditions in the ghettos deteriorated under an intensified German campaign of deprivation.

Perhaps the defining test of the courage and the character of Judenrat leaders occurred when the Germans ordered lists drawn up indicating those to be protected by work permits and those to be deported to concentration camps. Judenrat members knew that deportation meant near-certain death. Thus, while the Judenräte used tactics such as bribery, postponement, importuning, and appeasement to secure work permits for as many residents as possible, only a specified number of work permits were available and decisions were required. This became especially wrenching when it came to children and the elderly, who were incapable of working.

In Łódź, Rumkowski cooperated with the deportations. He argued, “I must cut off the limbs to save the body itself. I must take the children because if not, others will be taken as well. The part that can be saved is much larger than the part that must be given away.” Similar decisions were made by Judenrat leaders in Vilna (now Vilnius, Lithuania) and Sosnowiec.

In Warsaw, Czerniaków committed suicide rather than participate in the deportation of children and the liquidation of the entire ghetto. “They have asked me to kill the children with my own hands,” he said in despair. To some Jews, Czerniaków’s suicide was an act of integrity. Others saw it as a sign of weakness and condemned his failure to call for resistance.

When the Germans ordered the final liquidation of the ghetto, there could be little pretense that many Jews could be saved. The Jewish resistance in several ghettos began to take control. While some Judenrat leaders, such as Dr. Elchanan Elkes of Kovno (now Kaunas, Lithuania) and his counterpart in Minsk (now in Belarus), Eliyahu Mushkin, cooperated with the underground and the resistance, most Judenrat leaders considered the resistance a threat to their efforts to maintain order and sustain the ghettos. As a consequence, Judenrat leaders and Jewish police were often the first to be assassinated by the Jewish resistance, even before direct battle with the Germans.

At the end of the war, virtually all Judenrat leaders, regardless of their level of accommodation with the Germans, were dead. Rumkowski, who perhaps tried the hardest to cooperate with the Germans to save “the body” of his ghetto, met the same fate as that body—death at an extermination camp.

In her book Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), Hannah Arendt revived the controversy over the role of the Judenräte by implying that their complicity actually increased the Holocaust’s death toll. She wrote, “The whole truth was that if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between four and a half and six million people.” Her work triggered a storm of controversy but also provoked research that yielded a more subtle understanding of the impossible task these leaders faced in confronting the Nazis’ overwhelming power and fervent, disciplined commitment to annihilate the Jewish people.

ADDITIONAL READING

Raul Hilberg, “The Ghetto as a Form of Government,” in John K. Roth and Michael Berenbaum (eds.) Holocaust: Religious and Philosophical Implications (1989), pp. 116–135, explores the Judenrat in its historical and political context. Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, rev. and enlarged ed. (1964, reissued 1994), is a collection of provocative and controversial studies that argues, in part, that Judenrat members bore partial responsibility for the Holocaust. Isaiah Trunk, Judenrat: The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe Under Nazi Occupation (1972, reissued 1996), a wide-ranging and comprehensive study of all of the Judenräte in German-occupied eastern Europe, presents a more balanced view and refutes some of Arendt’s charges.

PURPOSE OF THE JUDENRAT

Wikipedia

Judenrat (plural: Judenräte; German for "Jewish council") was a widely used administrative agency imposed by Nazi Germany during World War II, predominantly within the ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe, and the Jewish ghettos in German-occupied Poland. The Nazi German administration required Jews to form a Judenrat in every community across the occupied territories.

The Judenrat constituted a form of self-enforcing intermediary, used by the Nazi administration to control larger Jewish communities in occupied areas. The Germans also implemented the name Jewish Council of Elders (Jüdischen Ältestenrat or Ältestenrat der Juden) in some ghettos, as in the Łódź Ghetto, and in Theresienstadt or in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. While the history of the term Judenrat itself is unclear, Jewish communities themselves had established councils for self-government as far back as the Medieval Era. While the Hebrew term of Kahal (קהל) or Kehillah (קהילה) was used by the Jewish community, German authorities generally tended to use the term Judenräte.

NAZI CONSIDERATIONS OF JEWISH LEGAL STATUS

The structure and missions of the Judenräte under the Nazi regime varied widely, often depending upon whether meant for a single ghetto, a city or a whole region. Jurisdiction over a whole country, as in Nazi Germany, was maintained by Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland (Reich's Association of the Jews in Germany) established on 4 July 1939.

In the beginning of April 1933, shortly after the National Socialist government took power, a report by a German governmental commission was presented on fighting the Jews. This report recommended the creation of a recognized 'Association of Jews in Germany' (Verband der Juden in Deutschland), to which all Jews in Germany would be forced to associate. Then, appointed by the Reichskanzler, a German People's Ward was to assume responsibility of this group. As the leading Jewish organization, it was envisioned that this association would have a 25-member council called the Judenrat. However, the report was not officially acted upon.

The Israeli historian Dan Michman found it likely that the commission, which considered the legal status and interactions of Jews and non-Jews before their emancipation, reached back to the Medieval Era for the term Judenräte. This illuminates the apparent intent to make the Jewish emancipation and assimilation invalid, and so return Jews to the status they held during the Medieval Era.

OCCUPIED TERRITORIES

The building of the Jewish Council in Warsaw, burned during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The first actual Judenräte were established in occupied Poland by Reinhard Heydrich's orders on 21 September 1939, soon after the end of the German assault on Poland and later the occupied territories of the Soviet Union.

The Judenräte were to serve as a means to enforce the occupation force's anti-Jewish regulations and laws in the western and central areas of Poland, and had no authority of their own. Ideally, a local Judenrat was to include Rabbis and other influential people of their local Jewish community. Thus, enforcement of laws could be better facilitated by the German authorities by using established Jewish authority figures and personages, while undermining external influences.

Further Judenräte were established on 18 November 1939, upon the orders of Hans Frank, head of the Generalgouvernment. These councils were to have 12 members for Jewish communities of 10,000 or fewer, and up to 24 members for larger Jewish communities. Jewish communities were to elect their own councils, and by the end of 1939 were to have selected an executive and assistant executive as well. Results were to be presented to the German city or county controlling officer for recognition. While theoretically democratic, in reality the councils were often determined by the occupiers. While the German occupiers only minimally involved themselves in the voting, those whom the Germans first chose often refused participation to avoid becoming exploited by the occupiers. As a rule, therefore, the traditional speaker of the community was named and elected, preserving the community continuity.

MISSIONS AND DUTIES

The Nazis systematically sought to weaken the resistance potential and opportunities of the Jews of Eastern Europe. The early Judenräte were foremost to report numbers of their Jewish populations, clear residences and turn them over, present workers for forced labour, confiscate valuables, and collect tribute and turn these over. Failure to comply would incur the risk of collective punishments or other measures. Later tasks of the Judenräte included turning over community members for deportation.

Through these occupation measures, and the simultaneous prevention of government services, the Jewish communities suffered serious shortages. For this reason, early Judenräte attempted to establish replacement service institutions of their own. They tried to organize food distribution, aid stations, old age homes, orphanages and schools. At the same time, given their restricted circumstances and remaining options, they attempted to work against the occupier's forced measures and to win time. One way was to delay transfer and implementation of orders and to try playing conflicting demands of competing German interests against each other. They presented their efforts as indispensable for the Germans in managing the Jewish community, in order to improve the resources of the Jews and to move the Germans to repeal collective punishments.

This had, however, very limited positive results. The generally-difficult situations presented often led to perceived unfair actions, such as personality preferences, sycophancy, and protectionism of a few over the rest of the community. Thus, the members of the community quickly became highly critical of, or even outright opposed their Judenrat.

GHETTO SITUATION

Judenräte were responsible for the internal administration of ghettos, standing between the Nazi occupiers and their Jewish communities. In general, the Judenräte represented the elite from their Jewish communities. Often, a Judenrat had a group for internal security and control, a Jewish Ordnungspolizei. They also attempted to manage the government services normally found in a city such as those named above. However, the requirements of the Nazis to deliver community members to forced labor, deportation or Nazi concentration camps placed them in the position of helping the occupiers. To resist such actions or orders was to risk summary execution or inclusion in the next concentration camp shipment, with a quick replacement.

In a number of cases, such as the Minsk ghetto and the Łachwa ghetto, Judenräte cooperated with the resistance movement. In other cases, Judenräte cooperated with the Nazis.

THE ROLE OF THE JUDENRÄTE IN THE HOLOCAUST

Hannah Arendt stated in her 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem that without the assistance of the Judenräte, the registration of the Jews, their concentration in ghettos and, later, their active assistance in the Jews' deportation to extermination camps, fewer Jews would have perished because the Germans would have encountered considerable difficulties in drawing up lists of Jews. In occupied Europe, the Nazis entrusted Jewish officials with the task of making such lists of Jews along with information about the property they owned. The Judenräte also directed the Jewish police to assist the Germans in catching Jews and loading them onto transport trains leaving for Nazi concentration camps.

In her book, Arendt wrote that: "To a Jew, this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story. [...] In the matter of cooperation, there was no distinction between the highly assimilated Jewish communities of Central and Western Europe and the Yiddish-speaking masses of the East. In Amsterdam as in Warsaw, in Berlin as in Budapest, Jewish officials could be trusted to compile the lists of persons and of their property..."[5]

Arendt's view has been challenged by other historians of the Holocaust, including Isaiah Trunk in his book Judenrat: The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe Under Nazi Occupation (1972). Summarising Trunk's research, Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum has written: "In the final analysis, the Judenräte had no influence on the frightful outcome of the Holocaust; the Nazi extermination machine was alone responsible for the tragedy, and the Jews in the occupied territories, most especially Poland, were far too powerless to prevent it.

JUDENRAT:: INTRODUCTORY HISTORY

As far back as 1933, Nazi policy makers had discussed establishing Jewish-led institutions to carry out anti-Jewish policies. The concept was based upon centuries-old practices which were instituted in Germany during the Middle Ages. As the German army swept through Poland and the Soviet Union, it carried out an order of S.S. leader Heydrich to require the local Jewish populace to form Jewish Councils as a liaison between the Jews and the Nazis. These councils of Jewish elders, (Judenrat; plural: Judenräte), were responsible for organizing the orderly deportation to the death camps, for detailing the number and occupations of the Jews in the ghettos, for distributing food and medical supplies, and for communicating the orders of the ghetto Nazi masters. The Nazis enforced these orders on the Judenrat with threats of terror, which were given credence by beatings and executions. As ghetto life settled into a "routine," the Judenrat took on the functions of local government, providing police and fire protection, postal services, sanitation, transportation, food and fuel distribution, and housing, for example.

The Judenrat raised funds to create hospitals, homes for orphans, disinfection stations, and to provide food and clothing to those without.

Jewish leaders were ambivalent about participating in these Judenröte. On the one hand, many viewed these councils as a form of collaboration with the enemy. Others saw these councils as a necessary evil, which would permit Jewish leadership a forum to negotiate for better treatment. In the many cases where Jewish leaders refused to volunteer to serve on the Judenrat, the Germans appointed Jews to serve on a random basis. Some Jews who had no prior history of leadership agreed to serve, hoping that it would improve their chances of survival. Many who served in the Judenrat were arrested, taken to labor camps, or hanged.

When the Nazis required a quota of Jews to participate in forced labor, the Judenrat had the responsibility to meet this demand. Sometimes Jews could avoid forced labor by making a payment to the Judenrat. These payments supplemented the taxes which the Judenrat levied to finance the services provided in the ghettos.

Underground Jewish organizations sprang up in the ghettos to serve as alternatives to the Judenrat, some of which were established with a military component to organize resistance to the Nazis.

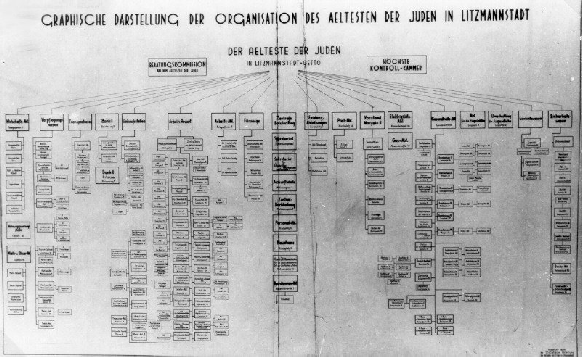

Organistion Chart of the Lodz Judenrat

From ‘The Judenrat "Council of Elders"

(This chart illustrates its complexity)

Introductory History

Activities of the Judenrat in the Generalgouvernement

Appeal for Contributions by the Judenrat in Bialystok

Celebration of the First Anniversary of the Judenrat in Bialystok

Establishment of Judenraete (Jewish Councils) in the Occupied Territories

Protocol of General Meeting of the Judenrat in Lublin

Protocol of a Session of the Judenrat in Bialystok

The Judenrat "Council of Elders Holocaust research project

|

Judenräte |

Judenräte |

HOLOCAUST

THE JUDENRÄTE (JEWISH COUNCILS)

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE