|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CLICK BUTTON TO GO |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Videos |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

SUMMARY

_________________________________

In 1953 Yad Vashem was created by the Israel Patliament (Knesset) to honour non-Jews who had risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews in countries that had been under Nazi rule or had collaborated with the German regime.

The rescue was through individuals or a group such as the Quakers who played a central role in bringing children from Germany before the start of WW2 (see Kindertransport) and during WW2 to diplomats who provided visas or individual(s) who gave a hiding place in their home or premises and underground organisations/groups. This often meant the construction of shelters where Jews remained, sometimes for weeks, months, and even years, without seeing the light of day. In addition to endangering their own lives, the rescuers would have had to supply food, medical assistance, clothing and daily necessities. There was a constant danger of informers who were always ready to betray them. The rescuer sometimes had to find ways to move the hidden Jews to other hiding places and/or finding ways to aid the Jews by providing forged documents that enabled them to live under false identities as non-Jews. Sometimes they helped by smuggling Jews across borders.

Denmark was exceptionally remarkable during the war as its citizens collectively saved all Danish Jews. As a result, Yad Vashem declared the entire country Righteous Among the Nations.

Yad Vashem has conferred the honor of Righteous Among the Nations upon 19,141 individuals. However, the number of rescue attempts was larger than the number of those recorded. There were additional rescuers who were not given the title. Research has shown that the number of rescuers was often equal to the number of Jews rescued and some times outnumbering them. Frequently it took more than one person to help one Jew survive the war.

Examples are given of some who tried to tell the world about the horrors of Nazi camps.

Rescue presented many difficulties. The Allied prioritization of "winning the war" and the lack of access to those who needed rescue hampered major rescue operations. Individuals willing to help Jews in danger faced severe consequences if they were caught, and formidable logistics of supporting people in hiding. Finally, hostility towards Jews among non-Jewish populations, especially in eastern Europe, was a daunting obstacle to rescue.

Whether they saved a thousand people or a single life, those who rescued Jews during the Holocaust demonstrated the possibility of individual choice even in extreme circumstances. These and other acts of conscience and courage, however, saved only a tiny percentage of those targeted for destruction.

‘

‘

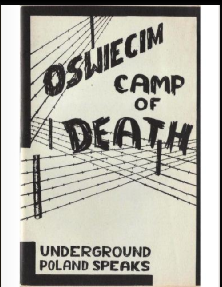

OSWIECIM (POLISH)

AUSCHWITZ (GERMAN), CAMP OF DEATH

1942 IN POLISH 1944 IN ENGLISH

BY NATALIA ZAREMBINA

(Polish Underground)

TO READ A COPY OF THIS BOOK (IN ENGLISH) GO TO

AND THEN CLICK ON THE COVER PAGE

The Righteous Among the Nations, honored by by Yad Vashem, are non-Jews who took great risks to save Jews during the Holocaust. Rescue took many forms and the Righteous came from different nations, religions and walks of life. What they had in common was that they protected their Jewish neighbors at a time when hostility and indifference prevailed.

Avenue of the Righteous Among the Nations

"I believe that it was really due to Lorenzo that I am alive today; and not so much for his material aid, as for his having constantly reminded me by his presence… that there still existed a just world outside our own, something and someone still pure and whole… for which it was worth surviving"

Primo Levi describes his rescuer, Lorenzo Perrone (If This Is A Man)

Attitudes towards the Jews during the Holocaust mostly ranged from indifference to hostility. The mainstream watched as their former neighbors were rounded up and killed; some collaborated with the perpetrators; many benefited from the expropriation of the Jews property.

In a world of total moral collapse there was a small minority who mustered extraordinary courage to uphold human values. These were the Righteous Among the Nations. They stand in stark contrast to the mainstream of indifference and hostility that prevailed during the Holocaust. Contrary to the general trend, these rescuers regarded the Jews as fellow human beings who came within the bounds of their universe of obligation.

Most rescuers started off as bystanders. In many cases this happened when they were confronted with the deportation or the killing of the Jews. Some had stood by in the early stages of persecution, when the rights of Jews were restricted and their property confiscated, but there was a point when they decided to act, a boundary they were not willing to cross. Unlike others, they did not fall into a pattern of acquiescing to the escalating measures against the Jews.

In many cases it was the Jews who turned to the non-Jew for help. It was not only the rescuers who demonstrated resourcefulness and courage, but also the Jews who fought for their survival. Wolfgang Benz, who did extensive research on rescue of Jews during the Holocaust claims that when listening to rescue stories, the rescued persons may seem to be only objects for care and charity, however “the attempt to survive in illegality was before anything else a self-assertion and an act of Jewish resistance against the Nazi regime. Only few were successful in this resistance”.

Faced with Jews knocking on their door, bystanders were faced with the need to make an instant decision. This was usually an instinctive human gesture, taken on the spur of the moment and only then to be followed by a moral choice. Often it was a gradual process, with the rescuers becoming increasingly involved in helping the persecuted Jews. Agreeing to hide someone during a raid or roundup - to provide shelter for a day or two until something else could be found – would evolve into a rescue that lasted months and years.

The price that rescuers had to pay for their action differed from one country to another. In Eastern Europe, the Germans executed not only the people who sheltered Jews, but their entire family as well. Notices warning the population against helping the Jews were posted everywhere. Generally speaking punishment was less severe in Western Europe, although there too the consequences could be formidable and some of the Righteous Among the Nations were incarcerated in camps and killed. Moreover, seeing the brutal treatment of the Jews and the determination on the part of the perpetrators to hunt down every single Jew, people must have feared that they would suffer greatly if they attempted to help the persecuted. In consequence, rescuers and rescued lived under constant fear of being caught; there was always the danger of denunciation by neighbors or collaborators. This increased the risk and made it more difficult for ordinary people to defy the conventions and rules. Those who decided to shelter Jews had to sacrifice their normal lives and to embark upon a clandestine existence – often against the accepted norms of the society in which they lived, in fear of their neighbors and friends – and to accept a life ruled by dread of denunciation and capture.

Most rescuers were ordinary people. Some acted out of political, ideological or religious convictions; others were not idealists, but merely human beings who cared about the people around them. In many cases they never planned to become rescuers and were totally unprepared for the moment in which they had to make such a far-reaching decision. They were ordinary human beings, and it is precisely their humanity that touches us and should serve as a model. The Righteous are Christians from all denominations and churches, Muslims and agnostics; men and women of all ages; they come from all walks of life; highly educated people as well as illiterate peasants; public figures as well as people from society's margins; city dwellers and farmers from the remotest corners of Europe; university professors, teachers, physicians, clergy, nuns, diplomats, simple workers, servants, resistance fighters, policemen, peasants, fishermen, a zoo director, a circus owner, and many more.

Scholars have attempted to trace the characteristics that these Righteous share and to identify who was more likely to extend help to the Jews or to a persecuted person. Some claim that the Righteous are a diverse group and the only common denominator are the humanity and courage they displayed by standing up for their moral principles. Samuel P. Oliner and Pearl M. Oliner defined the altruistic personality. By comparing and contrasting rescuers and bystanders during the Holocaust, they pointed out that those who intervened were distinguished by characteristics such as empathy and a sense of connection to others. Nehama Tec who also studied many cases of Righteous, found a cluster of shared characteristics and conditions of separateness, individuality or marginality. The rescuers’ independence enabled them to act against the accepted conventions and beliefs.

Bystanders were the rule, rescuers were the exception. However difficult and frightening, the fact that some found the courage to become rescuers demonstrates that some freedom of choice existed, and that saving Jews was not beyond the capacity of ordinary people throughout occupied Europe. The Righteous Among the Nations teach us that every person can make a difference.

There were different degrees of help: some people gave food to Jews, thrusting an apple into their pocket or leaving food where they would pass on their way to work. Others directed Jews to people who could help them; some sheltered Jews for one night and told them they would have to leave in the morning. Only few assumed the entire responsibility for the Jews’ survival. It is mostly the last group that qualifies for the title of the Righteous Among the Nations.

The main forms of help extended by the Righteous Among the Nations:

Hiding Jews in the rescuers' home or on their property. In the rural areas in Eastern Europe hideouts or bunkers, as they were called, were dug under houses, cowsheds, barns, where the Jews would be concealed from sight. In addition to the threat of death that hung over the Jews' heads, physical conditions in such dark, cold, airless and crowded places over long periods of time were very hard to bear. The rescuers, whose life was terrorized too, would undertake to provide food – not an easy feat for poor families in wartime – removing the excrements, and taking care of all their wards' needs. Jews were also hidden in attics, hideouts in the forest, and in any place that could provide shelter and concealment, such as a cemetery, sewers, animal cages in a zoo, etc. Sometimes the hiding Jews were presented as non-Jews, as relatives or adopted children. Jews were also hidden in apartments in cities, and children were placed in convents with the nuns concealing their true identity. In Western Europe Jews were mostly hidden in houses, farms or convents.

Providing false papers and false identities - in order for Jews to assume the identity of non-Jews they needed false papers and assistance in establishing an existence under an assumed identity. Rescuers in this case would be forgers or officials who produced false documents, clergy who faked baptism certificates, and some foreign diplomats who issued visas or passports contrary to their country's instructions and policy. Diplomats in Budapest in late 1944 issued protective papers and hung their countries flags over whole buildings, so as to put Jews under their country's diplomatic immunity. Some German rescuers, like Oskar Schindler, used deceitful pretexts to protect their workers from deportation claiming the Jews were required by the army for the war effort.

Smuggling and assisting Jews to escape – some rescuers helped Jews get out of a zone of special danger in order to escape to a less dangerous location. Smuggling Jews out of ghettos and prisons, helping them cross borders into unoccupied countries or into areas where the persecution was less intense, for example to neutral Switzerland, into Italian controlled parts where there were no deportations, or Hungary before the German occupation in March 1944.

The rescue of children - parents were faced with agonizing dilemmas to separate from their children and give them away in the hope of increasing their chances of survival. In some cases children who were left alone after their parents had been killed would be taken in by families or convents. In many cases it was individuals who decided to take in a child; in other cases and in some countries, especially Poland, Belgium, Holland and France, there were underground organizations that found homes for children, provided the necessary funds, food and medication, and made sure that the children were well cared for.

ABOUT THE PROGRAM

One of Yad Vashem’s principal duties is to convey the gratitude of the State of Israel and the Jewish people to Righteous Among the Nations who took great risks to save Jews during the Holocaust.

"In those times there was darkness everywhere. In heaven and on earth, all the gates of compassion seemed to have been closed. The killer killed and the Jews died and the outside world adopted an attitude either of complicity or of indifference. Only a few had the courage to care. These few men and women were vulnerable, afraid, helpless - what made them different from their fellow citizens?… Why were there so few?… Let us remember: What hurts the victim most is not the cruelty of the oppressor but the silence of the bystander…. Let us not forget, after all, there is always a moment when moral choice is made…. And so we must know these good people who helped Jews during the Holocaust. We must learn from them, and in gratitude and hope, we must remember them."

Elie Wiesel, in Carol Rittner, Sandra Meyers, Courage To Care - Rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust, NYU Press, 1986. P. 2

MILESTONES IN THE HISTORY OF THE RIGHTEOUS PROGRAM >>>

Yad Vashem was established to perpetuate the memory of the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust. One of Yad Vashem’s principal duties is to convey the gratitude of the State of Israel and the Jewish people to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. This mission was defined by the law establishing Yad Vashem, and in 1963 the Remembrance Authority embarked upon a worldwide project to grant the title of Righteous Among the Nations to the few who helped Jews in the darkest time in their history. To this end, Yad Vashem set up a public Commission, headed by a Supreme Court Justice, which examines each case and is responsible for granting the title. Those recognized receive a medal and a certificate of honor and their names are commemorated on the Mount of Remembrance in Jerusalem.

This project is a unique and unprecedented attempt by victims to pay tribute to people who stood by their side at a time of persecution and great tragedy. Based on the principle that each individual is responsible for his or her deeds, the program is aimed at singling out within the nations of perpetrators, collaborators and bystanders, persons who bucked the general trend and helped the persecuted Jews. Thus, when Yad Vashem was established in 1953, a mere eight years after the Shoah, paying tribute to the Righteous Among the Nations was included in the Remembrance Authority’s mission. Struggling with the enormity of the loss and grappling with the impact of the total abandonment and betrayal Europe’s Jews, the State of Israel remembered the rescuers. The program therefore is a testament to the resilience of the victims, who despite their having come face to face with the most extreme manifestation of evil, did not sink into bitterness and revenge and affirmed human values. In a world where violence more often than not only breeds more violence, this is a unique and remarkable phenomenon. It probably stems from the notion that if one was to build a future in a world where Auschwitz had become a real possibility, it was essential to emphasize that Man was also capable of defending and maintaining human values.

I AM MY BROTHER'S KEEPER

Yad Vashem

Milestones. Significant milestones marking the first five decades of the Righteous Among the Nations program.

Photo Gallerie Moving photo galleries featuring Righteous Among the Nations and the Rescuers together with those they saved.

Themes Five themes depicting dilemmas, choices and issues facing the Rescuers and the Jews they attempted to help.

FEATURED STORIES

Yad Vashem

Featured here are several dozen stories of Righteous Among the Nations arranged by topics and by countries. All the Righteous Among the Nations recognized by Yad Vashem are included in the Database of the Righteous.

Examples of the stories are:

- The “Pianist”’s Rescuer: Wilhelm (Wilm) Hosenfeld

- Rescue in the Sewers: Leopold & Magdalena Socha

- The Nanny That Kept Her Promise: Gertruda Bablinska

- The Port Worker Who Turned Rescuer: Jan and Johana Lipke

NAMES OF RIGHTEOUS BY COUNTRY

Yad Vashem

Names and Numbers of Righteous Among the Nations - per Country & Ethnic Origin, as of January 1, 2019

The numbers of Righteous are not necessarily an indication of the actual number of rescuers in each country, but reflect the cases that were made available to Yad Vashem.

* The title of Righteous is awarded to individuals, not to groups. The members of the Danish resistance viewed the rescue operation as a collective act and therefore asked Yad Vashem not to recognize resistance members individually. Yad Vashem respected their request and consequently the number of Danish Righteous is relatively small. A tree was planted on the Mount of Remembrance to commemorate the Danish resistance.

See also

Talk:List of Righteous Among the Nations by country Wikipedia

By country and ethnic origin Wikipedia This list has detail by country and links from each country

Commemorating the Righteous Among the Nations at Yad Vashem. The History of a Unique Program Yad Vashem

ABOUT STATISTICS

The question is often asked what can be learned from the numbers of Righteous and from the proportions between different nations about attitudes and the scope of rescue in the respective countries.

It needs to be noted that the numbers of Righteous recognized do not reflect the full extent of help given by non-Jews to Jews during the Holocaust; they are rather based on the material and documentation that was made available to Yad Vashem. Most Righteous were recognized following requests made by the rescued Jews. Sometimes survivors could not overcome the difficulty of grappling with the painful past and didn’t come forward; others weren’t aware of the program or couldn’t apply, especially people who lived behind the Iron Curtain during the years of Communist regime in Eastern Europe; other survivors died before they could make the request. An additional factor is that most cases that are recognized represent successful attempts; the Jews survived and came forward to tell Yad Vashem about them.

For example: Researchers estimate that 5000-7,000 Jews went underground in Berlin. They are the so-called U-Boote (submarines), who made the difficult choice to enter an illegal existence rather than be deported. Only a quarter of them – around 1200-1500 Jews – survived. It is unknown how many were killed in the bombing of Berlin, but all the others were caught and deported. For lack of information and evidence, not all the Germans who risked their lives to help these Jews were honored.

Before drawing any statistical conclusions about the proportions between different countries, one should bear in mind that although the Holocaust was a global and total attempt to annihilate the Jews all over occupied Europe, there were important differences between countries – differences in the number of Jews, the implementation of the Final Solution, the type of German or other administration, the historical backdrop, the makeup of the Jewish community, Germany’s attitude to the local population and the extent of danger to those who helped Jews, and a multitude of other factors that influenced the disposition and attitudes of local populations and the feasibility of rescue.

FAQ’S Yad Vashem

Answers to questions such as the following

Who is a Righteous Among the Nation?

Righteous Among the Nations is an official title awarded by Yad Vashem on behalf of the State of Israel and the Jewish people to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. The title is awarded by a special commission headed by a Supreme Court Justice according to a well-defined set of criteria and regulations.

What is the meaning of the term "Righteous Among the Nations"?

The term “Righteous Among the Nations” (Chasidei Umot HaOlam) was taken from the Jewish tradition – from the literature of the Sages. A number of explanations of the term exist, such as: non-Jews who came to the aid of the Jewish people in times of danger; in other cases it is used to describe non-Jews who observe seven basic tenets set down in the Bible – including the prohibition of bloodshed. The lawmakers took the existing term and added new meaning to it. The Yad Vashem Law went on to characterize the Righteous Among the Nations as those who not only saved Jews but risked their lives in doing so. This was to become the basic criterion for awarding the title.

JEWISH RESCUE

United States Holocaust Museum

Despite the indifference of most Europeans and the collaboration of others in the murder of Jews during the Holocaust, individuals in every European country and from all religious backgrounds risked their lives to help Jews. Rescue efforts ranged from the isolated actions of individuals to organized networks both small and large.

Rescue of Jews during the Holocaust presented a host of difficulties. The Allied prioritization of "winning the war" and the lack of access to those who needed rescue hampered major rescue operations. Individuals willing to help Jews in danger faced severe consequences if they were caught, and formidable logistics of supporting people in hiding. Finally, hostility towards Jews among non-Jewish populations, especially in eastern Europe, was a daunting obstacle to rescue. Rescue took many forms.

German-occupied Denmark was the site of the most famous and complete rescue operation in Axis-controlled Europe. In late summer 1943, German occupation authorities imposed martial law on Denmark in response to increasing acts of resistance and sabotage. German Security Police officials planned to deport the Danish Jews while martial law was in place. On September 28, 1943, a German businessman warned Danish authorities of the impending operation, scheduled for the night of October 1–2, 1943. With the help of their non-Jewish neighbors and friends, virtually all the Danish Jews went into hiding. During the following days, the Danish resistance organized a rescue operation, in which Danish fishermen clandestinely ferried some 7,200 Jews (of the country's total Jewish population of 7,800) in small fishing boats, to safety in neutral Sweden.

In the so-called Generalgouvernement (German-occupied Poland), some Poles provided assistance to Jews. For instance, Zegota (code name for Rada Pomocy Zydom, the Council for Aid to Jews), a Polish underground organization that provided for the social welfare needs of Jews, began operations in September 1942. Although members of the nationalist Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa-AK) and the communist Polish People's Army (Armia Ludowa-AL) assisted Jewish fighters by attacking German positions during the Warsaw ghetto uprising in April 1943, the Polish underground provided few weapons and only a small amount of ammunition to Jewish fighters. From the beginning of the deportation of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto to the Treblinka killing center in late July 1942 until the German occupiers leveled Warsaw in the autumn of 1944 after suppressing the Home Army uprising, as many as 20,000 Jews were living in hiding in Warsaw and its environs with the help of Polish civilians.

Rescuers came from every religious background: Protestant and Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Muslim. Some European churches, orphanages, and families provided hiding places for Jews, and in some cases, individuals aided Jews already in hiding (such as Anne Frank and her family in the Netherlands). In France, the Protestant population of the small village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon sheltered between 3,000 and 5,000 refugees, most of them Jews. In France, Belgium, and Italy, underground networks run by Catholic clergy and lay Catholics saved thousands of Jews. Such networks were especially active both in southern France, where Jews were hidden and smuggled to safety to Switzerland and Spain, and in northern Italy, where many Jews went into hiding after Germans occupied Italy in September 1943.

A number of individuals also used their personal influence to rescue Jews. In Budapest, the capital of German-occupied Hungary, Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg (who was also an agent of the US War Refugee Board), Swiss diplomat Carl Lutz, and Italian citizen Giorgio Perlasca (posing as a Spanish diplomat), provided tens of thousands of Jews in 1944 with certification that they were under the "protection" of neutral powers. These certifications exempted the bearers from most anti-Jewish measures decreed by the Hungarian government, including deportation to the Greater German Reich. Each of these rescuers worked closely with members of the Budapest Jewish communities. For example, Perlasca, whose credentials were the most vulnerable to challenge, worked closely with Otto Komoly and the Szamosis—Laszlo and Eugenia—to obtain protective papers and shelter for scores of Jews in Budapest.

The Sudeten German industrialist Oskar Schindler took over an enamelware factory located outside the Krakow ghetto in German-occupied Poland. He later protected over a thousand Jewish workers employed there from deportation to the Auschwitz concentration camp. The deportation of more than 11,000 Jews from Bulgarian-occupied Thrace, Macedonia, and Pirot to Treblinka in March 1943 by the Bulgarian military and police authorities shocked and shamed key political, intellectual, and religious figures in Bulgaria into an open protest against any deportations from Bulgaria proper. The protest action, which included members of the government's own ruling party, induced the Bulgarian King, Boris III, to reverse the decision of his government to comply with the German request to deport the Jews of Bulgaria. As a result of Boris' decision, the Bulgarian authorities did not deport any Jews from Bulgaria proper.

Other non-Jews, such as Jan Karski, a courier for the Polish government-in-exile, based in London, to the non-communist underground movements, sought to expose Nazi plans to murder the Jews. Karski met with Jewish leaders in the Warsaw ghetto and in the Izbica transit ghetto in late summer of 1942. He transmitted their reports of mass killings in the Belzec killing center to Allied leaders, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, with whom he met in July 1943.

On November 15, 1938, following the violence of Kristallnacht, November 9-10, 1938, a delegation of British Jewish leaders, including Lord Bearstead, the Chief Rabbi, Neville Laski Rothschild and Chaim Weizmann, appealed in person to the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain.

The British government eased immigration restrictions for certain categories of Jewish refugees, agreeing to permit an unspecified number of children under 17 years of age to enter Great Britain from Germany and German-annexed Austria and Czech lands.

Private citizens or organizations had to guarantee to pay for each child's care, education, and eventual emigration from Britain. in return for the British government's agreement to allow unaccompanied refugee children to enter the country on temporary travel visas, with the understanding that that when the crisis was over, the children would return to their families.

Parents or guardians could not accompany the children.

In Britain, the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany, headed by Elaine Laski and Lola Hahn Warburg, coordinated many of the rescue efforts, while Jews, Quakers, and Christians of several denominations worked together to bring refugee children to Britain.

About half of the children lived with foster families.

The others stayed in hostels, schools, or on farms throughout Britain.

10,000 children came to Britain and 1,000 went to the USA. They came on a project known as Kindertransport (from Kindertransport.Info)

Whether they saved a thousand people or a single life, those who rescued Jews during the Holocaust demonstrated the possibility of individual choice even in extreme circumstances.

These and other acts of conscience and courage, however,

saved only a tiny percentage of those targeted for destruction.

INDIVIDUALS AND GROUPS

ASSISTING JEWS DURING THE HOLOCAUST

These are examples of reports that were supplied and then ignored

of what the Nazis were doing

RUDOLF VRBA and ALFRED WETZLER REPORT

Wikipedia

Wetzler is known for the report that he and his fellow escapee, Rudolf Vrba, compiled about the inner workings of the Auschwitz camp – a ground plan of the camp, construction details of the gas chambers, crematoria and, most convincingly, a label from a canister of Zyklon B. The 33-page Vrba–Wetzler report, as it became known, released in mid 1944, was the first detailed report about Auschwitz to reach the West that the Allies regarded as credible (in 1943, Polish officer Witold Pilecki wrote and forwarded his own report to the Polish government in exile and, through it, to the British and other Allied governments). The evidence eventually led to the bombing of several government buildings in Hungary, killing Nazi officials who were instrumental in the railway deportations of Jews to Auschwitz. The deportations from Hungary halted after Hungarian-Romanian Jew George Mantello, then First Secretary of the El Salvador mission in Switzerland, publicized the report, which led to the saving of up to 120,000 Hungarian Jews.

The historian Sir Martin Gilbert said: "Alfred Wetzler was a true hero. His escape from Auschwitz, and the report he helped compile, telling for the first time the truth about the camp as a place of mass murder, led directly to saving the lives of thousands of Jews – the Jews of Budapest who were about to be deported to their deaths. No other single act in the Second World War saved so many Jews from the fate that Hitler had determined for them

see also Auschwitz Protocols above

JERZY TABEAU

After escaping from Auschwitz he wrote a report on conditions there. It was circulated between 1943/44

Wikipedia

Jerzy Tabeau (18 December 1918 in Zabłotów–11 May 2002) was a Polish medical student who was one of the first escapees from Auschwitz to give a fully detailed report on the genocide occurring there to the outside world. First reports in early 1942 had been made by the Polish officer Witold Pilecki. Tabeau's report was known as that of the "Polish major"

Reports on the general genocide were already widely available, including the 10 December 1942 Polish Government in Exile address to the League of Nations, and evidence such as from an escaped Jewish inmate from Majdanek, Dionys Lenard.[8] However limited information about the death production line at Auschwitz was available.

Several escapees from the camp had already passed some information outside: On 20 June 1942 the three Poles Kazimierz Piechowski, Stanisław Gustaw Jaster, Józef Lempart and the Ukrainian Eugeniusz Bendera escaped, with a report of Witold Pilecki passing his information to the Polish Home Army (AK). On 27 April 1943 Witold Pilecki himself, a Polish Home Army agent who had deliberately infiltrated the camp in order to found Związek Organizacji Wojskowej (ZOW) cells inside it and to take measures against the German extermination policy of the Polish intelligentsia, escaped together with two other Polish soldiers, Jan Redzej and Edward Ciesielski. Each compiled a separate report for the Polish Home Army. Witold's report was translated into English but was filed away by the British government with a note saying there was no indication as to the source's reliability.

On 2 November 1943 Kazimirez Halori, another Polish prisoner, escaped and passed information to the Polish Socialist Party. Natalia Zarembina, another Polish escapee wrote a report entitled "Auschwitz—Camp of Death" which was published in English in 1943 in London.

Tabeau compiled his report between December 1943 and January 1944. It was copied using a stencil machine in Geneva in August 1944, and was distributed by the Polish government-in-exile and Jewish groups.[9] This was presented in the Protocols as the 19-page "No 2. Transport (The Polish Major's Report)."[10] The contents of the Protocols was discussed in detail by The New York Times on 26 November 1944.

JAN KARSKI

Jan Karski, was an underground courier for the Polish government-in-exile. He was one of the first to deliver to western powers eyewitness accounts of Nazi atrocities in the Warsaw ghetto and deportations of Jews to killing centers.

Holocaust Encyclopedia

Jan Karski was born Jan Kozielewski to a Roman Catholic family in Lodz in 1914. After completing his university studies, Karski joined the Polish diplomatic service.

At the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, he joined the Polish army but was soon taken prisoner by the Soviets and sent to a detention camp in what is now Ukraine. Karski escaped and joined the Polish underground movement.

With his knowledge of geography and foreign languages and a remarkable memory, Karski became a resourceful courier. He conveyed secret information between the resistance and the Polish government-in-exile. In late 1940, while on a mission, Karski was captured by the Gestapo and brutally tortured. Fearing that under duress he might reveal secrets, Karski slashed his wrists, but was sent to a hospital from which the underground helped him escape.

In late 1942 Karski was smuggled in and out of the Warsaw ghetto and a transit camp at Izbica, where he saw for himself the horrors suffered by Jews under Nazi occupation, including mass starvation and transports of Jews en route to the Belzec killing center. Karski then traveled to London where he delivered a report to the Polish government-in-exile and to senior British authorities including Foreign Minister Anthony Eden. He described what he had seen and warned of Nazi Germany’s plans to murder European Jews. In July 1943 Karski journeyed to Washington and met with American President Franklin D. Roosevelt to give the same warning and plead for action.

Allied governments were focused on the military defeat of Germany, and Karski’s message was greeted with disbelief or indifference. Disheartened, Karski remained in the United States where he earned a PhD from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service. Karski refused to return to Communist Poland. Instead, he remained in Washington promoting Polish freedom and serving for many decades as a professor at Georgetown.

Spurred by the memory of the Holocaust, for the rest of his life Karski worked tirelessly for Polish-Jewish understanding and to honor the memory of all victims of Nazism. In addition to receiving the highest Polish civic and military decorations, Karski was made an honorary citizen of Israel and was awarded the distinction “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem. Karski died in Washington, DC, in July 2000.

Go to Wikipedia, The Envoy, Yad Vashem,

Jan Karski Dies at 86; Warned West About Holocaust, NY Times, July 15, 2000,

Jan Karski Educational Foundation

ARAB AND MUSLIM

RESCUE EFFORTS DURING THE HOLOCAUST

Wikipedia

A number of Arabs participated in efforts to help save Jewish residents of Arab lands from the Holocaust while fascist regimes controlled the territory. From June 1940 through May 1943, Axis powers, namely Germany and Italy, controlled large portions of North Africa. Approximately 1 percent of the Jewish residents, about 4,000 to 5,000 Jews, of that territory were murdered by these regimes during this period. The relatively small percentage of Jewish casualties, as compared to the 50 percent of European Jews who were murdered during the Holocaust, is largely due to the successful Allied North African Campaign and the repelling of the Axis powers from North Africa.

No occupied country in Africa or Europe was free of collaboration with the genocide campaign against the Jews, but this was more common in European countries than Arab ones. The offer made to Algerians by colonial French officials to take over confiscated Jewish property found many French settlers ready to profit from the scheme, but no Arab participated and, in the capital, Algiers itself, Muslim clerics openly declared their opposition to the idea. While some Arabs collaborated with the Axis powers by working as guards in labor camps[citation needed], others risked their own lives to attempt to save Jews from persecution and genocide.

Arab rescue efforts were not limited to the Middle East – Si Kaddour Benghabrit, the rector of the Great Mosque of Paris, according to different sources, helped from 100 to 500 Jews disguise themselves as Muslims. There are examples of non-Arab Muslim populations assisting Jews to escape from the Holocaust in Europe, in Albania for example. In September 2013, Yad Vashem declared an Egyptian doctor, Mohammed Helmy, one of the Righteous Among the Nations for saving the life of Anna Gutman (née Boros), putting himself at personal risk for three years, and for helping her mother Julie, her grandmother Cecilie Rudnik, and her stepfather Georg Wehr, to survive the holocaust. Helmy is the first Arab to have been so honoured.

COUNTRYMEN:

THE UNTOLD STORY OF HOW DENMARK'S JEWS

ESCAPED THE NAZIS

Why did Jews in some countries - in particular Denmark -

fare better than in others?

The Guardian Ian Buruma,Thu 13 Mar 2014

* The title of Righteous is awarded to individuals, not to groups. The members of the Danish resistance viewed the rescue operation as a collective act and therefore asked Yad Vashem not to recognize resistance members individually. Yad Vashem respected their request and consequently the number of Danish Righteous is relatively small. A tree was planted on the Mount of Remembrance to commemorate the Danish resistance.

See Table Above

Sir Anthony Eden once spoke the following words, in perfect French: "One who has not suffered the horrors of an occupying power has no right to judge a nation that has." He was referring to France under Nazi occupation.

Eden's sentiment was correct. And yet the question that has been nagging many people since the second world war is why the record of some nations appears to have been so much better than others. Why, for example, did more than 70% of Dutch Jews disappear into the death camps, while almost all the Jews in Denmark managed to get away safely?

The relative degree of antisemitism does not offer a conclusive answer. There was anti-Jewish prejudice in both countries, but not, as Isaiah Berlin once nicely put it, "more than necessary". There was no violence against Jews. A reasonably assimilated Jewish middle-class was well established in both nations. Impoverished Jews, many of them in Amsterdam, were less assimilated, but they were not threatened either, until the Germans came.

Were the Danes more courageous in opposing Nazi plans, or were they simply nicer people – like the Italians, who also managed to protect a large number of Jews from mass murder?

Ranking entire nations in terms of niceness is probably an idea to be resisted: societies are too diverse for that. But how do we explain the discrepancies, between Holland and Denmark, or Poland, where most Jews were murdered, and Bulgaria, where many survived?

Bo Lidegaard, in this magisterial study of wartime Denmark, claims that his country's admirable record owes much to the way Danish citizens saw themselves and their society. He writes: "The Danish exception shows that the mobilisation of civil society's humanism and protective engagement is not only a theoretical possibility: It can be done. We know because it happened." The harming of Denmark's Jews went against everything most Danes believed in, especially their concept of the rule of law. Even injustice, he writes, "needs a semblance of law. That is hard to find when the entire society denies the right of the stronger."

The story he tells of how Danes, from the top bureaucrats, Church leaders and police officials down to the humblest fishermen, helped the Jews escape when the Germans tried to deport them to concentration camps in October 1943, is indeed astonishing and heart-warming.

From the moment they knew it was coming, Danish government officials made it clear to their policemen that no help was to be given to the Germans. Doors were opened everywhere, often to complete strangers, for Jews to hide. Fishermen living along the rugged Danish coast loaded their cutters and schooners with thousands of refugees and ferried them across to Sweden. They were often generously paid for taking the risk. But penniless Jews, who had fled from eastern Europe or were members of the Danish working class, were never rejected.

And all this was openly supported by King Christian. He did not, contrary to popular myth, ride his horse through Copenhagen wearing the Star of David, but he did make it clear, as he wrote in his diary, that he considered "our own Jews to be Danish citizens, and the Germans could not touch them". The Dutch Queen Wilhelmina may have felt the same way about Jews in her country, but she never stated it as openly as her Danish colleague, even from her safe base in wartime London.

The humanism of the Danish rescuers, and their king, is not in doubt. Helping people in mortal danger was a matter of common decency, which was not always in such abundant supply in other parts of Europe. Again and again, Lidegaard turns to a political explanation: "Danish democracy mobilised itself to protect the values on which it was based."

To the fisherfolk, according to Lidegaard, it was also a matter of local honour. A school consultant told his fellow citizens in a coastal village from which many Jews managed to escape: "History will be written these days in this town."

However, there is no reason to think that the Dutch, or the Norwegians, or the Belgians, were any less attached to their democratic institutions or their idea of the rule of law. To observe, as Lidegaard does, that Denmark benefited from circumstances that were substantially different from those in other countries under Nazi occupation, does not detract from the moral courage f Danish citizens, but does help explain some of the discrepancies in Europe.

First, there were very few Jews in Denmark, about 6,000, compared to about 140,000 in Holland, and more than 3 million in Poland. Most of them were so assimilated as to be indistinguishable from other Danes. Also, it was relatively easy to escape to neighbouring Sweden, which was not under German occupation. And neutral Sweden, realising by 1943 that the Third Reich was in retreat, welcomed the Jewish refugees. This act of humanity was boosted, perhaps, by a desire to show that Sweden would be on the winning side.

The most important factor, however, was the highly ambivalent attitude of the Germans themselves. Unlike Sweden, Denmark was not free from Nazi occupation, but a special deal had been struck. Hitler wanted Denmark to be his model protectorate. Like the Swedes, the Danes would supply the Reich with agricultural goods and other economic assistance. They would crack down on domestic resistance. And in return, they retained their own government, as well as their cherished democratic institutions.

Holland, by contrast, was under direct Nazi rule; its government had fled to London in 1940, along with the Queen. Much of France was still administered by a French government, which was neither liberal, nor democratic. Central European countries were either annexed by the Reich or ruled by Nazi governors.

Swedish neutrality and the Danish deal with Nazi Germany were not heroic. But these arrangements provided the necessary flexibility to do the right thing. In a way, it was precisely their unheroic accommodation that allowed them to behave decently. As long as the Germans remained keen to keep Denmark as a somewhat autonomous protectorate, it was not in their interest to agitate the Danes. And the Danes made it very plain that any attempt to deport the Jews would agitate them very much.

It also helped that the decision to attack the Jews in Denmark came late – in 1943 – and suddenly. There was no gradual isolation of the Jewish population through cumulative measures, which often met with relatively little protest in other occupied countries: the barring from certain jobs or public places, the yellow star, and so on.

Also, by 1943, even some of the fiercest Nazi officials were becoming a little nervous about the possible consequences of what they were doing in case the Reich should collapse. This would explain the two-faced and oddly equivocal actions of the top Nazi official in Denmark, SS General Werner Best, and of his chief German adviser, Georg Duckwitz, who told the Danes exactly when and where the attack on the Jews would take place.

At that stage, relations between Nazi Germany and its model protectorate were in a delicate phase anyway, because the elected Danish government had already resigned in protest against the imposition of martial law. If the Danish bureaucrats who continued to administer the country were to quit as well, the German-Danish deal would break down, which would not only mean a loss of face in Berlin, but also hinder the steady supply of Danish goods to the Reich.

That is why Werner Best assured his boss, Heinrich Himmler, that he would take care of the Jewish problem in Denmark, while at the same time hinting to the Danes that he would limit the scope of the deportations. He may even have been complicit in Duckwitz's tip-off about the impending action, which allowed most Jews to go into hiding. What is sure is that neither the German army, nor the navy, nor even Nazi officials in Denmark, apart from a few zealots, did very much to stop the boats from ferrying their loads of refugees to Swedish ports.

Lidegaard is right: "The special Danish example cannot be used to reproach others who experienced the German occupation under far worse conditions than Denmark." But the Danes made the very best out of their easier circumstances. And for that, they should always be remembered as an example of civility at a time when there was precious little of it.

• Ian Buruma's most recent book is Year Zero: A History of 1945.

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

NON-JEWS WHO HELPED JEWS

DURING WWII

Sir Martin Gilbert

University of California Television (UCTV) 2008 (15.25)

How, as the Third Reich carried out its program to

exterminate European Jewry,

many Gentiles risked their careers and lives to conceal and rescue

Jewish refugees.

"HARRY'S STORY" -

MEMORIES OF HIDING JEWS

AND NAZI BRUTALITY DURING WWII

Ken Hook 2017 (36.54)

Harry Andringa was only 9 years old and living in Holland when Adolf Hitler's Nazis invaded the Netherlands. Harry's family endured the horrors and atrocities of the Nazi regime for 5 years until Holland was liberated by the Allies.

Many families including Harry's hid Jewish children to prevent them from being sent to concentration camps. This documentary includes a interview with Harry and supported by vintage war footage from the Canadian Army Newsreels - courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada.

Harry used to visit local schools during Remembrance Day services and other times when he was invited to talk to students about WWII. His story is preserved in this documentary so it will not be forgotten.

Please share with others. Thank You!

THE DEVELOPMENT

OF THE "FINAL SOLUTION"

Yad Vashem 2015 (11.41)

This video is part of the Holocaust Education Video Toolbox. For more videos and teaching aids, visit: https://www.yadvashem.org/education/e...

In the video, "The Development of the 'Final Solution'", Dr. David Silberklang

provides an overview of what came to

be known as the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question", which ended in the murder of some six million Jews. Dr. Silberklang identifies several major steps, sometimes occuring concurrently, including the prewar separation and escalating anti-Jewish measures, exploring a territorial solution, increasing murder during the German territorial expansion, murder in other countries and of other groups, early attempts at mass-murder systems, the "Wansee Conference", and the fully mechanized mass-murder of the final years of the War.

Dr. David Silberklang is Senior Historian and Editor of Yad Vashem Studies at theInternational Institute for Holocaust Research, Yad Vashem.

Part 1: Introduction 00:00

Part 2: Persecution and Murder Beyond Germany’s Borders 3:32

Part 3: Systematic Murder Begins and Spreads 5:04

Part 4: The “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” 9:58

THE POLISH UNDERGROUND AND THE JEWS, 1939–1945

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research 2016 (1.19.15)

Ruth Gay Seminar in Jewish Studies

In this lecture, Joshua Zimmerman (Yeshiva University) confronts one of the central sources of contention in Polish-Jewish history: the Polish Underground’s treatment of Jews during WWII. Drawing on archival documents, testimonies, and memoirs Zimmerman’s new book The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945 (Cambridge, 2015), argues that the Polish Underground’s reaction to the Holocaust in fact varied greatly, ranging from aggressive aid to murder. Analyzing the military, civilian, and political wings of the Polish Underground and offering portraits of the organization's main leaders, this book is the first full-length scholarly monograph in any language to provide

a thorough examination of the subject.

HOLOCAUST LECTURE -

FLOWERS FOR THE HEINEMANNS:

HIDDEN HISTORY OF HELPING JEWS

IN NAZI GERMANY

utdarts 2019 (1.20.22)

Brought to you by the Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies at the University of Texas at Dallas as part of the Burton C. Einspruch Holocaust Lecture Series.

This year’s lectures were presented by Dr. Mark Roseman, the Pat M Glazer Chair in Jewish Studies at Indiana University Bloomington.

Using the remarkable example of a little-known oppositional group in Nazi Germany, the lecture explores the challenges and opportunities of helping Jews in the Third Reich, and the motives for doing so. It asks why those who lived under Nazi rule and took on the regime found it hard after the war to articulate what they had been through, and why much of their experience disappeared from memory. With the help of some unique wartime documents, the lecture seeks to recover a lost world of

thought and action during the Holocaust.