|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Payments to Jailed Palestinians and ‘Martyrs’ by the Palestinian AuthorityP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

Taking power in a civil war from the PLO Israel found it had a country ruled by a terrorist group one of whose principal aims is it’s destruction (see charter) to control access and exit. The other entry point is controlled by Egypt which is often closed and when open, strictly controlled

The 2014 war in Gaza created a humanitarian crisis and caused US$1.7 billion in losses to the economy, which continues to suffer to this day. Even though growth in the Gaza Strip reached 7.3% in 2016, due to increased construction, Gaza’s economy is not expected to rebound to its pre-2014 war level until 2018. Alongside its stunted recovery, Gaza suffers from severe shortages of electricity with rolling blackouts.

In 2016, the unemployment rate remained stubbornly high

at 27%: 42 % in Gaza and 18% in the West Bank.

Youth unemployment in Gaza is particularly worrying at 58%.

And, although nearly 80% of Gaza’s residents receive some form of aid,

poverty rates are very high. (World Bank)

CLICK HERE FOR HAMAS COVENANT AND HISTORY

1922 -1948 Under British memorandum

1948-1967 Egyptian army trapped in Gaza at end of war with Israel. Then came under Egyptian sovereignty though not made Egyptian citizens

1967 Under Israel sovereignty

2004 First Israeli Gaza war

2005 Israel withdraw’s its troops and 7,000 settlers

2007 Hamas takes over government of Gaza

2008 Second Israeli Gaza War

2014 Third Israeli Gaza war

2018 Gaza Border Protests

GAZA STRIP

Encyclopedia Brittanica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

GEOGRAPHY

OFFICIAL NAME(S)

Gaza Strip; Qiṭāʿ Ghazzah (Arabic); Reẓuʿat ʿAzza (Hebrew)

POPULATION

(2019 est.) 1,992,000

TOTAL AREA (SQ MI) 141 TOTAL AREA (SQ KM) 365

The Gaza Strip is situated on a relatively flat coastal plain. Temperatures average in the mid-50s F (about 13 °C) in the winter and in the upper 70s to low 80s F (mid- to upper 20s C) in summer. The area receives an average of about 12 inches (300 mm) of precipitation annually.

Living conditions in the Gaza Strip are typically poor for a number of reasons: the region’s dense and rapidly increasing population (the area’s growth rate is one of the highest in the world); inadequate water, sewage, and electrical services; high rates of unemployment; and, from September 2007, sanctions imposed by Israel on the region.

Agriculture is the economic mainstay of the employed population, and nearly three-fourths of the land area is under cultivation. The chief crop, citrus fruit, is raised on irrigated lands and is exported to Europe and other markets under arrangement with Israel. Truck crops, wheat, and olives also are produced. Light industry and handicrafts are centred in Gaza, the chief city of the area.

In politically stable times, as much as one-tenth of the Palestinian population travels daily to Israel (where they are not allowed to stay overnight) to work in menial jobs. Political tension and outbreaks of violence often led Israeli authorities to close the border for extended periods, putting many Palestinians out of work. As a result, a thriving smuggling industry emerged, based on a network of subterranean tunnels linking parts of the Gaza Strip with neighbouring Egypt. The tunnels provided Palestinians with access to goods such as food, fuel, medicine, electronics, and weapons.

HISTORY

OCCUPATION

After rule by the Ottoman Empire ended there in World War I (1914–18), the Gaza area became part of the League of Nations mandate of Palestine under British rule. Before this mandate ended, the General Assembly of the United Nations (UN) in November 1947 accepted a plan for the Arab-Jewish partition of Palestine under which the town of Gaza and an area of surrounding territory were to be allotted to the Arabs. The British mandate ended on May 15, 1948, and on that same day the first Arab-Israeli war began. Egyptian forces soon entered the town of Gaza, which became the headquarters of the Egyptian expeditionary force in Palestine. As a result of heavy fighting in autumn 1948, the area around the town under Arab occupation was reduced to a strip of territory 25 miles (40 km) long and 4–5 miles (6–8 km) wide. This area became known as the Gaza Strip. Its boundaries were demarcated in the Egyptian-Israeli armistice agreement of February 24, 1949.

The Gaza Strip was under Egyptian military rule from 1949 to 1956 and again from 1957 to 1967. From the beginning, the area’s chief economic and social problem was the presence of large numbers of Palestinian Arab refugees living in extreme poverty in squalid camps. The Egyptian government did not consider the area part of Egypt and did not allow the refugees to become Egyptian citizens or to migrate to Egypt or to other Arab countries where they might be integrated into the population. Israel did not allow them to return to their former homes or to receive compensation for their loss of property. The refugees were maintained largely through the aid of the UNRWA. Many of the younger refugees became fedayeen (Arab guerrillas operating against Israel); their attacks on Israel were one of the causes precipitating the Sinai campaign during the Suez Crisis of 1956, when the strip was taken by Israel. The strip reverted to Egyptian control in 1957 following strong international pressures on Israel.

In the Six-Day War of June 1967, the Gaza Strip was again taken by Israel, which occupied the region for the next quarter century. In December 1987 rioting and violent street clashes between Gaza’s Palestinians and occupying Israeli troops marked the birth of an uprising that came to be known as the intifadah (Arabic intifāḍah, “shaking off”). In 1994 Israel began a phased transfer of governmental authority in the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority (PA) under the terms of the Oslo Accords that were signed by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The fledgling Palestinian government, led by Yasser Arafat, struggled with such problems as a stagnant economy, divided popular support, stalled negotiations with Israel over further troop withdrawals and territoriality, and the threat of terrorism from militant Muslim groups such as Islamic Jihad and Hamas, which refused to compromise with Israel and were intent on derailing the peace process. Beginning in late 2000, a breakdown in negotiations between the PA and Israel was followed by a further, more extreme outbreak of violence, termed the second, or Aqṣā, intifadah. In an effort to end the fighting, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon announced in late 2003 a plan that centred on withdrawing Israeli soldiers and settlers from the Gaza Strip. In September 2005 Israel completed the pullout from the territory, and control of the Gaza Strip was transferred to the PA, although Israel continued to patrol its borders and airspace.

Under Hamas’s governance

In the 2006 PA parliamentary elections, Fatah—which had dominated Palestinian politics since its founding in the 1950s—suffered a decisive loss to Hamas, reflecting years of dissatisfaction with Fatah’s governance, which was criticized as corrupt and inefficient. Hamas’s victory prompted sanctions by Israel, the United States, and the European Union, each of which had placed the organization on its official list of terrorist groups. The Gaza Strip was the site of escalating violence between the competing groups, and a short-lived coalition government was ended in June 2007 after Hamas took control of the Gaza Strip and a Fatah-led emergency cabinet took control of the West Bank. Despite calls by PA Pres. Mahmoud Abbas for Hamas to relinquish its position in the Gaza Strip, the territory remained under Hamas’s control.

Attempts at reconciliation with Fatah

A number of attempts were made to reconcile with the Fatah-led PA. An initial deal was reached in 2011 but did not bring about much change. A new deal was achieved in 2014, in which Hamas agreed to hand over administration of the Gaza Strip to the PA and recognize the prime ministership of Rami Hamdallah. As such, the Hamas government in the Gaza Strip resigned, including the prime minister, Ismail Haniyeh. The PA was not allowed to resume control of public institutions in the Gaza Strip until late 2017, however, after implementation of a new agreement. The PA failed to gain full governance in the area, though, and decided to cut funding to the Gaza Strip in 2018. As disagreements continued to escalate, the PA ceased operating the Rafah border crossing with Egypt in January 2019. Later that month Hamdallah resigned, ending the unity government.

BLOCKADE

In autumn 2007 Israel declared the Gaza Strip under Hamas a hostile entity and approved a series of sanctions that included power cuts, heavily restricted imports, and border closures. In January 2008, facing sustained rocket assaults into its southern settlements, Israel broadened its sanctions, completely sealing its border with the Gaza Strip and temporarily preventing fuel imports. Later that month, after nearly a week of the intensified Israeli blockade, Hamas’s forces demolished portions of the barrier along the Gaza Strip–Egypt border (closed from Hamas’s mid-2007 takeover until 2011), opening gaps through which, according to some estimates, hundreds of thousands of Gazans passed into Egypt to purchase food, fuel, and goods unavailable under the blockade. Egyptian Pres. Hosni Mubarak temporarily permitted the breach to alleviate civilian hardship in Gaza before efforts could begin to restore the border.

Hamas Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh (left) and the emir of Qatar, Sheikh Ḥamad bin Khalīfa Āl Thānī, arriving at a cornerstone-laying ceremony for a new residential neighbourhood in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, 2012.

In the years after the Israeli blockade on Gaza was instated, an organization known as the Free Gaza Movement made a number of maritime efforts to breach it. The first such mission—which consisted of a pair of vessels bearing medical supplies and some 45 activists—was permitted to reach Gaza in August 2008, and four missions in subsequent months were also successful. In May 2010 a flotilla bound for Gaza was the scene of a clash between activists and Israeli commandos in which 9 of the more than 600 activists involved were killed.

Under Mubarak, Egypt’s cooperation in enforcing the blockade was deeply unpopular with the Egyptian public. In May 2011, four months after a popular uprising in Egypt forced Mubarak to step down as president, Egypt’s interim government announced that it would permanently reopen the Rafah border crossing, allowing Palestinians to pass between Egypt and Gaza. About 1,200 people were allowed to cross the border daily, though it remained closed for trade. However, in the turmoil following the ouster of Egyptian Pres. Mohamed Morsi in the summer of 2013, traffic through the border crossing was reduced to 50 people per day because of security concerns and was later closed altogether.

After the PA took control of the Rafah border crossing in late 2017, Egypt began allowing 200 people per day to cross the border in May 2018. The border was closed briefly after the PA quit the Gaza Strip in January 2019, but it was reopened weeks later by Hamas. During this rare and prolonged easing of the border, tens of thousands of Gazans were reported to have permanently emigrated from the Gaza Strip.

After months of violence between Israel and Hamas in mid-2018, Israel began to ease restrictions on its blockade as a part of an effort to incentivize a more long-term cease-fire agreement between the two. In 2019 Israel allowed the flow of additional goods into and out of the territory, expanded the permitted fishing zone for Gazans to its largest extent in more than a decade, and began allowing thousands of Gazans to cross the border to work in Israel.

Qatar, meanwhile, began offering tens of millions of dollars in humanitarian aid to the Gaza Strip at the end of 2018, after both Israel and Egypt agreed to allow the aid. By 2020 it had disbursed more than $150 million to the territory.

CONFLICT WITH ISRAEL

In June 2008, after months of back-and-forth strikes and incursions, Israel and Hamas agreed to implement a truce scheduled to last six months. However, this was threatened shortly thereafter as each accused the other of violations, which escalated in the last months of the agreement. When the truce officially expired on December 19, Hamas announced that it did not intend to extend it. Broader hostilities erupted shortly thereafter as Israel, responding to sustained rocket fire, mounted a series of air strikes across the region—among the strongest in years—meant to target Hamas. After a week of air strikes, Israeli forces initiated a ground campaign into the Gaza Strip amid calls from the international community for a cease-fire. Following more than three weeks of hostilities—in which perhaps more than 1,000 were killed and tens of thousands were left homeless—Israel and Hamas each declared a unilateral cease-fire.

Beginning on November 14, 2012, Israel launched a series of air strikes in Gaza, in response to an increase in the number of rockets fired from Gaza into Israeli territory over the previous nine months. The head of the military wing of Hamas, Ahmed Said Khalil al-Jabari, was killed in the initial strike. Hamas retaliated with increasing rocket attacks on Israel, and fighting continued until the two sides reached a cease-fire agreement on November 21.

In June 2014 three Israeli teenagers were kidnapped; Israel conducted a massive crackdown in the West Bank and increased air strikes in the Gaza Strip, prompting retaliatory rocket fire from Hamas. As fighting continued to escalate, Israel launched a 50-day offensive into the Gaza Strip on July 8. Over 2,100 Palestinians and more than 70 Israelis were killed in the ensuing conflict, with over 5,000 targets hit in the Gaza Strip. Despite the devastation, Hamas’s handling of the conflict was viewed positively by Palestinians and boosted the group’s popularity.

In the spring of 2018 a series of protests along the border with Israel, which included attempts to cross the border and flying flaming kites, was met with a violent response from Israel. Both the protests and the violence reached a peak on May 14 when about 40,000 Gazans attended the protests. When many of them tried to cross the border at once, Israeli troops opened fire, killing about 60 people and wounding 2,700 others. The violence escalated into military strikes from Israel and rocket fire from Hamas and continued for several months.

Amid the occasional skirmishes, and as Egypt tried to mediate a long-term truce between them, Israel and Hamas appeared to make some effort to de-escalate tense situations. In October, when rocket fire from the Gaza Strip hit Israel, Israel concluded that the rockets had been set off by a lightning strike. In November a covert Israeli operation in the Gaza Strip was exposed, and Hamas responded by firing hundreds of rockets into Israel. Israel retaliated with more than 100 air strikes. The two sides quickly agreed to a truce, however, and, throughout 2019 and into 2020, they continued to negotiate a long-term “understanding” for the maintenance of peace and easing of the blockade. The discussions, though occasionally interrupted by brief outbreaks of tit-for-tat violence, were reinforced by halted border protests and a loosening of the restrictions on trade and travel through the Gaza border.

The founder and first leader of Hamas was Sheik Ahmed Yassin

HAMAS Leadership

Hamas named militant commander Yehiya Sinwar as its new leader in the Gaza Strip on 13 February 2017, placing one of the Islamic militant group's most hard-line figures in charge of its core power base. The appointment of Sin

war, who was freed by Israel in a 2011 prisoner swap after two decades behind bars, solidified the takeover of Gaza operations by the armed wing of the group from civilian leaders. The military wing, which controls thousands of fighters and a vast arsenal of rockets, has battled Israel in three wars since Hamas seized Gaza a decade ago. The militant wing tends to take more hard-line positions toward Israel, while the politicians, who are tasked with improving the difficult living conditions in Gaza, tend to be more pragmatic. (For full article go to Global Security

THE HAMAS COVENANT OR HAMAS CHARTER

formally known in English as the Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement, was originally issued on 18 August 1988 and outlines the founding identity, stand, and aims of Hamas (the Islamic Resistance Movement).

ISRAEL-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT:

LIFE IN THE GAZA STRIP

Home to 1.9 million people, Gaza is 41km (25 miles) long and 10km wide,

an enclave bounded by the Mediterranean Sea, Israel and Egypt.

BBC 15 May 2018

Originally occupied by Egypt, which retains control of Gaza's southern border, the territory was captured by Israel during the 1967 Middle East war. Israel withdrew its troops and around 7,000 settlers in 2005.

(Editors Note

THE FUTURE

Today we talk and read about the deaths, injuries and problems of Gazans. If instead of having a government (Hamas) whose vision was the destruction of Israel it had a democratic government concerned with local prosperity then the prosperity that exists for a few could apply to all. Gazans, instead of living in perpetual conflict with Israel, would welcome Israeli and other tourists. It would be living in peace with Israel, Egypt and other countries and not fighting them. The siege mentality and resulting mental health problems would vanish. Environmental facilities including health, education, job and business prospects and accommodation would be vastly improved. The walls around their country would be torn down and the airport brought back into operation. Hamas will be a bad memory.

Do two things to test this statement

1. Go to Videos Gaza and Hamas

2. Go to The good news about Gaza you won’t hear on the BBC from The Spectator, 9 February 2018. )

FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT

Already limited, freedom of movement and access to Gaza were reduced significantly after mid-2013, when Egypt put new restrictions in place at the Rafah border crossing and launched a crackdown on the network of smuggling tunnels under the Egypt-Gaza border.

Egypt has effectively kept the border closed since October 2014, only opening it in exceptional circumstances. According to a report by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the Rafah crossing was partially open for only 17 days up to April 2018, with 23,000 registered and waiting for permission to cross.

In the north, crossings into Israel at Erez have picked up marginally this year compared with 2017, but remain well below pre-blockade levels due to new restrictions.

Fewer than 240 Palestinians left Gaza via Israel in the first half of 2017, compared with a daily average of 26,000 in September 2000.

ECONOMY

Tunnels were dug under the Egyptian border to bring in all kinds of goods, and weapons

Gaza is significantly poorer than it was in the 1990s. Its economy grew only 0.5% in 2017 according to a World Bank report, with annual income per person falling from $2,659 in 1994 to $1,826 in 2018.

In 2017 the Gaza Strip had the highest unemployment rate in the World Bank's development database.

At 44% it was more than double the rate in the West Bank.

Cash-Strapped Gaza and an Economy in Collapse Put Palestinian Basic Needs at Risk

Jerusalem, September 25, 2018 –The economy in Gaza is collapsing, suffering from a decade long blockade and a recent drying up of liquidity, with aid flows no longer enough to stimulate growth according to a new World Bank report. The result is an alarming situation with every second person living in poverty and the unemployment rate for its overwhelmingly young population at over 70 percent. (World Bank, September 25 2018)

And of particular concern was the high youth unemployment rate, which stood at more than 60% in Gaza.

The latest data shows Gaza's poverty rate stands at 39%, more than twice the rate in the West Bank. The World Bank believes this would rise even higher were it not for social aid payments, mostly through the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA).

The agency says 80% of the population are on some form of social assistance.

EDUCATION

IGaza's school system is under pressure. According to UNRWA, 94% of schools run a "double shift" system, with one school of students in the morning and another in the afternoon.

While UNRWA runs around 250 schools in the territory, which has pushed the literacy rate up to 97%, non-UN schools have suffered. The 2014 conflict damaged 547 schools, kindergartens and colleges, many of which have yet to be repaired.

This means there are larger and larger class sizes, with the UN reporting an average classroom of around 40 pupils in 2017.

A report by the UN Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) predicts the number of students in Gaza will grow from 630,000 in 2015 to 1.2 million by 2030, which means the Strip will need 900 more schools and 23,000 more teachers.

POPULATION

Gaza has one of the highest population densities in the world. On average, some 5,479 people live on every square kilometre in Gaza. That's expected to rise to 6,197 people per square kilometre by 2020.

The number of people living there is expected to hit 2.2 million by the end of the decade, and 3.1 million by 2030.

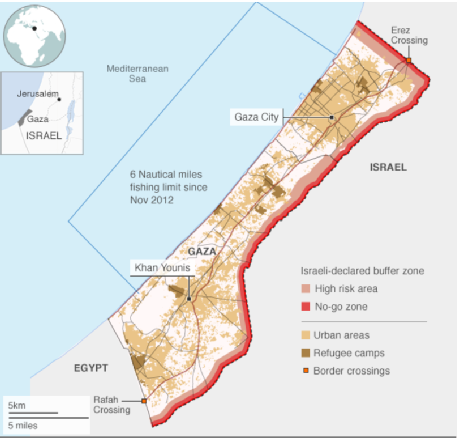

Israel declared a buffer zone along the border in 2014 to protect itself from rocket attacks and tunnels. The zone reduces the amount of land available for people to live or farm on.

The UN says there is a shortage of 120,000 housing units due to natural population growth, as well as damage caused by the 2014 conflict. They believe around 29,000 people remain displaced more than three years after the end of the conflict.

Gaza also has one of the world's youngest populations, with more than 40% younger than 15 years old.

HEALTH

Electricity and fuel shortages have disrupted the functioning of medical facilities

Access to public health services has worsened due to border restrictions.

The closure of the Rafah crossing reduced the number of patients travelling to Egypt for treatment. Before 2014, the World Health Organisation (WHO) said a monthly average of 4,000 people crossed into Egypt for health reasons alone.

Exit passes through Israel have also dropped in recent years, with approvals for medical reasons dropping from 93% in 2012 to 54% in 2017.

Moreover, drugs, supplies and equipment are all restricted because of the blockade - including dialysis machines and heart monitors.

Just as in education, the UN helps out by running 22 healthcare facilities. But a number of hospitals and clinics were damaged or destroyed in previous conflicts with Israel, with the total number of primary health care clinics falling from 56 to 49 since 2000 - in the same time as the population doubled.

A recent fuel shortage for generators has also affected medical services. The Palestinian Ministry of Health says three hospitals and ten medical centres have suspended services due to a lack of power.

FOOD

Not so long ago, Gaza had a thriving fishing industry

More than a million people in Gaza are classed as "moderately-to-severely food insecure", according to the UN, despite many receiving some form of food aid.

Israeli restrictions on access to agricultural land and fishing add to the challenges.

Gazans are not allowed to farm in the Israeli-declared buffer zone - 1.5km (0.9 miles) wide on the Gaza side of the border - and this has led to a loss in production of an estimated 75,000 tonnes of produce a year.

The restricted area coincides with what is considered Gaza's best arable land, and the Strip's agriculture sector has dropped from 11% of GDP in 1994 to less than 5% in 2018.

Israel imposes a fishing limit meaning Gazans can only fish within a certain distance of the shore. The UN says if the limit were lifted, fishing could provide employment and a cheap source of protein for the people of Gaza.

Following the November 2012 ceasefire agreement between Israel and Hamas, the fishing limit was extended from three nautical miles to six. However, it has been periodically reduced to three nautical miles in response to rocket fire from Gaza. Israeli naval forces frequently open fire towards Palestinian fishing boats approaching or exceeding the limit.

POWER

Power cuts in Gaza disrupt almost all aspects of daily life

Power cuts are an everyday occurrence in Gaza. On average, Gazans get only three-six hours of electricity a day.

The Strip gets most of its power from Israel together with further contributions from Gaza's only power plant and a small amount from Egypt. However, this all amounts to less than a third of the power it needs, according to the World Bank.

PA 'stops paying for Gaza electricity'

Both the Gaza Power Plant (GPP) and many people's individual generators depend on diesel fuel, which is very expensive and in short supply.

Offshore there is a gas field which the UN says could provide all the territory's power needs if it were developed. Any surplus could be ploughed into development.

The GPP was originally designed to run on natural gas, and the World Bank estimates reconverting the plant to run on gas would save millions of dollars and increase output fivefold.

WATER AND SANITATION

Heavy rainfall has overwhelmed Gaza's storm water and sewage systems in the past

Gaza has little rain and no major fresh water source to replenish its underground water supplies, which are not large enough to keep up with demand.

While most Gaza households are on a piped water network, the World Bank says supply is inconsistent and often poor quality. 97% of Gaza households depend on water delivered by tanker trucks.

Sewage is another problem. Although 78% of households are connected to public sewage networks, treatment plants are overloaded. Around 90 million litres of partially treated and raw sewage is pumped in to the Mediterranean and open ponds daily - meaning 95% of groundwater in the Strip is polluted.

There is also the risk that this sewage can flow into the streets, which could cause further health problems in the territory.

GAZA: THE BASICS

Some history and background on the Gaza Strip.

Slate By Nina Rastogi JAN. 25 2008

On Wednesday, tens of thousands of Palestinians streamed into Egypt for a shopping frenzy after gunmen in the Gaza Strip destroyed part of the barrier along the border. In the past two weeks, following a rise in rocket attacks, Israel had ramped up its blockades, refusing to allow anything besides humanitarian supplies to pass into the region. Below, the Explainer tackles a few basic questions about the region.

WHAT EXACTLY IS THE GAZA STRIP?

The Gaza Strip is a roughly rectangular territory surrounding the city of Gaza, wedged between the Mediterranean Sea and Israel. To the southwest, it shares a seven-mile border with Egypt. The region has a long history of occupation—by the ancient Egyptians, the Philistines, the Arabs, the Christian Crusaders, and the Ottomans. After World War I, the Gaza area became part of the British Mandate of Palestine, and it was occupied by Egypt in 1948, in the aftermath of the first Arab-Israeli war. Israel took control of the region during the Six-Day War in 1967, along with the West Bank, eastern Jerusalem, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula.

In 1994, Israel withdrew from parts of the Gaza Strip as part of its obligations under the Oslo Accords (which also affirmed the rights of the Palestinians to self-government). The Palestinian National Authority and Israel shared power in the Gaza Strip for the next 10 years, with the PNA administering civilian control and the Israelis overseeing military affairs as well as the borders, airspace, and remaining Israeli settlements.

In 2005, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon unilaterally ended military rule in the region and withdrew all Israeli settlements, thus bringing all areas of the Gaza Strip under Palestinian administration. * In 2007, Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip, causing a division between the region and the other Palestinian territory, the West Bank, where the Fatah party is dominant.

HOW DID IT COME TO BE THAT SHAPE?

The rectangular Gaza Strip is about 25 miles long and three to seven miles wide. One long side lies along the Mediterranean. One short, straight end borders Egypt: This follows the border that existed between Egypt and the British Mandate of Palestine. The other sides of the rectangle—a long, ragged edge and a shorter, northeastern side—separate the Gaza Strip from Israel. This border was established after the first Arab-Israeli War, which also resulted in the creation of Israel. The Gaza region became Egypt's military headquarters during the 1948 conflict, and the narrow coastal strip saw heavy fighting. When the cease-fire was announced later that year—following a decisive Israeli victory—the final position of the military fronts became what's known as "the Green Line," or the border between the Palestinian territories (both the Gaza Strip and the West Bank) and Israel.

WHO LIVES ON THE GAZA STRIP?

Since the withdrawal of Israeli settlements, the Gazan population is almost entirely Palestinian Arab. More than 99 percent are Sunni Muslims, with a very small number of Christians. The region saw a huge influx of Palestinian refugees after the creation of Israel in 1948—within 20 years, the population of Gaza had grown to six times its previous size. The Gaza Strip now has one of the highest population densities in the world: Almost 1.5 million people live within its 146 square miles. Eighty percent of Gazans live below the poverty line.

WHO BUILT THE FENCE BETWEEN GAZA AND EGYPT? WHO CONTROLS THE BORDER?

In 1979, Israel and Egypt signed a peace treaty that returned the Sinai Peninsula, which borders the Gaza Strip, to Egyptian control. As part of that treaty, a 100-meter-wide strip of land known as the Philadelphi corridor was established as a buffer zone between Gaza and Egypt. Israel built a barrier there during the Palestinian uprisings of the early 2000s. It's made mostly of corrugated sheet metal, with stretches of concrete topped with barbed wire.

In 2005, when Israel pulled out of the Gaza Strip, Israel and Egypt reached a military agreement regarding the border, based on the principles of the 1979 peace treaty. The agreement specified that 750 Egyptian border guards would be deployed along the length of the border, and both Egypt and Israel pledged to work together to stem terrorism, arms smuggling, and other illegal cross-border activities.

From November 2005 until July 2007, the Rafah Crossing—the only entry-exit point along the Gaza-Egypt border—was jointly controlled by Egypt and the Palestinian Authority, with the European Union monitoring Palestinian compliance on the Gaza side. After the Hamas takeover in June 2007, the European Union pulled out of the region, and Egypt agreed with Israel to shut down the Rafah Crossing, effectively sealing off the Gaza Strip on all sides.

GAZA MILITARY WING

Israel Defence Forces

Hamas’ military wing, the cornerstone of the movement, is a manifestation of the ideology of resistance (Muqawama). During its brief history, the military wing, called the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades, has carried out hundreds of terror attacks against Israeli civilians. In total, Hamas has committed over 90 suicide and bombing attacks, launched nearly 12,000 rockets and 5,000 mortars and has killed over 650 innocent civilians.

In a terror campaign it led in the 1990’s, Hamas carried out suicide bombings at restaurants, buses and public venues, killing hundreds of Israelis and derailing the fragile peace process. At the onset of the second Intifada, Hamas intensified its terrorist activity, culminating in a suicide attack at a Passover dinner at the "Park Hotel" (27 March, 2002) that resulted in 30 dead and 155 wounded civilians. Almost 40% of suicide attacks by Palestinians in 2000-2005 were committed by Hamas.

Hamas’ military power is also the main reason for its decade-long control of the Gaza Strip. After Hamas’ parliamentary victory in 2006, it sought to strengthen its grip on the Gaza Strip by establishing its own security force ("The Executive Force"), which answers only to the Hamas-controlled Interior Ministry. The Executive Force and the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades were the main forces that took over the Gaza Strip during the Hamas-led coup and the subsequent purge of Fatah rivals.

The period of 2006-2009 saw no decrease in Hamas' propensity for conflict with Israel. After Hamas took over Gaza, it quickly intensified the mortar and rocket fire from Gaza into Israel, with rocket attacks rising from 488 in 2005 to 2,427 in 2007. Some of Hamas’ main targets were the civilian crossings into Gaza, which were routinely attacked by mortar and rocket fire, terrorist raids, tunnels and suicide attacks. The relentless attacks against the civilian lifeline of Gaza have greatly curtailed the operation of the crossings, and ultimately necessitated the shutdown of some (Karni, Sufa) and relocation of their operations to Kerem-Shalom. The process has reduced the capacity for economic and civilian ties between Israel and Gaza, further exacerbating the economic hardship in Gaza. Hamas has attempted to replace the ties with Israel with ties to Egypt vis-à-vis the "tunnel economy," gaining significant dividends from controlling the trade and smuggling. However, these efforts ran afoul of the Egyptian authorities after Hamas orchestrated a popular storming of the border between them, as well as because of Hamas' ties with terror groups in the Sinai Peninsula.

Aside from their economic benefit, the tunnels also became a leading operational tool for Hamas. Hamas used tunnels for its operations throughout its rule, including in the abduction of Gilad Shalit in 2006. In recent years, Hamas has invested heavily in upgrading its tunnel operations and has constructed an expansive tunnel network covering most urban areas of Gaza. The tunnels are used for military purposes including weapons storage, concealed maneuvering, covert rocket launch sites and even for offensive attacks. This terror infrastructure is embedded in civilian areas, and uses civilian buildings as entry points, as well as cover for the tunnels themselves.

The military wing is an integral part of Hamas and not a separate entity. High-level military operatives are part of the Hamas leadership and have a prominent role in decision making. The military wing has been headed by Ahmed Jabari, Muhammad Deif and Yahiya Sinwar. Sinwar, a convicted murderer with a long history of involvement in the military wing, was appointed in February 2016 as the Hamas Chief in the Gaza Strip, replacing Ismail Haniyeh. Sinwar’s seamless transition from military to political leadership demonstrates that there is no real separation between these two wings of the movement.

GAZA NEEDS CEMENT TO REBUILD,

BUT ISRAEL DOMINATES THE MARKET

Israeli-Palestinian politics hamper the pace of recovery in the territory

Bloomberg BusinessWeek,

David Rocks and Yaacov Benmeleh and 15 August 2019

Mohamad al-Assar was asleep when his factory was bombed. On a steamy night in August 2014, he was awakened not by the explosion but by a phone call from the security guard at the plant. The concrete-mixing factory, 2 miles north of his home and adjacent to the only highway in the Gaza Strip, had been attacked in the final days of the seven-week war between Israel and Islamist militants. When al-Assar got there at dawn, he saw nothing but devastation. Two neighbors were dead. The offices had been reduced to rubble. The storage silos were heaps of metal. An 18-wheel concrete-pumping truck had been thrown across the road. “I just sat in the ruins and cried,” al-Assar says, scrolling through photos of the destruction on his phone.

He knew he had to open again; the plant provided a living for al-Assar and his 40 workers. But building any kind of factory requires tons of cement. In al-Assar’s case, about 100 tons. Problem is, sales of cement are strictly regulated in Gaza, and al-Assar had little time. Buying cement legally would have required detailed plans and myriad approvals, and he had customers who needed to rebuild. So in January 2015 he did what almost everyone in Gaza has gotten accustomed to after decades of Israeli occupation and blockade: He went to the black market. He paid about double the going rate of just over $100 per ton, but he managed to restart production by that March. “I needed to get things moving,” he says in the factory’s crowded control room, where an ancient computer monitors the combination of ingredients to make concrete.

Gaza needs concrete, and lots of it. In the 2014 war, some 11,000 housing units were destroyed, and an additional 160,000 sustained some damage, according to the Gaza Chamber of Commerce—affecting more than a quarter of the families in the territory. Today, five years after the fighting ended, some 16,500 people remain in temporary housing, according to the United Nations. Gaza’s streets are lined with half-built structures, where a handful of floors are occupied but the rest are windowless shells. Older buildings are pockmarked and crumbling from decades of neglect or damage in various conflicts. It’s common to see groups of men clambering over piles of debris, breaking up slabs of concrete to recycle what they can. To repair war damage, carry out normal upkeep, and build planned projects over the past five years, Gaza needed at least 6 million tons of cement, the chamber says. It’s gotten less than half that relates to Gaza Needs Cement to Rebuild, But Israel Dominates the Market

Like just about everything having to do with Palestinian-Israeli relations, supplying cement to Gaza is intensely political. The market is dominated by Nesher Israel Cement Enterprises, which gets about a third of its revenue from contractors who build homes for Jewish settlers on occupied land in the West Bank and controls almost three-fourths of legal sales in Gaza. Deliveries are governed by the Gaza Reconstruction Mechanism, or GRM, the complex set of rules al-Assar faced. That system monitors so-called dual-use materials—things needed by civilians that also have potential military applications. Israel restricts shipments of more than 100 broad categories of goods, ranging from smoke detectors and glues to precast concrete sewage conduits and iron reinforcement bars.

The biggest and most contentious commodity is cement, something that’s rarely, if ever, been considered a dual-use material. It’s easy to confuse it and concrete. The former is the builder’s equivalent of glue, the stuff that binds the sand and gravel that make up the bulk of concrete, which is used in just about every structure in the industrialized world. Making cement isn’t complicated—the recipe hasn’t changed appreciably in two centuries—but it requires vast amounts of energy and facilities the size of a small city. Ideally, a cement factory will be located adjacent to a limestone quarry. The limestone is crushed, combined with clay and small amounts of additives such as ash or iron ore, and heated to 1,500C (2,700F). What comes out the other end is called clinker—a dark, rocky substance that looks something like charcoal briquettes. The clinker is mixed with a bit of gypsum or limestone and ground into a powder that becomes cement.

“I just sat in the ruins and cried”

The driving force behind the GRM was a Dutch diplomat named Robert Serry, who was the UN’s chief peace negotiator in the region. In September 2014, just a few weeks after the fighting ended, Serry met with Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank to broker an agreement to speed reconstruction. With international donors expected to pledge more than $5 billion in aid at a conference in Cairo that October, someone needed to monitor shipments of supplies to building sites. “It would have made no sense without some sort of mechanism to get goods into Gaza,” Serry recalls. “Everybody started to look to the UN for a solution.”

What many in Gaza still call “the Serry Plan” faced intense skepticism. Israeli military brass were especially concerned about keeping Hamas—the Islamist group that rules Gaza, deemed by the U.S., the European Union, and Israel to be a terrorist organization—from getting its hands on materials that could be used to build tunnels for sneaking into Israel. But by late September, the two sides came to an agreement. While the GRM has seen millions of tons of cement enter Gaza from Israel in the past five years, many Gazans say the plan slowed reconstruction and helped ignite a black market for goods smuggled through tunnels under the border with Egypt. “The goal was to keep Hamas from getting cement,” says Maher al–Tabbaa, an official with the Gaza Chamber of Commerce. “But cement from Egypt was available to anyone, Hamas or not.”

Cement sales highlight the push-me-pull-you relationship between Israelis and Palestinians. The two sides hate, they fight, they kill, they cooperate—then the cycle begins again. And it’s getting more complicated as other Middle East players wade in. Many Gazans buy cement from a factory owned by the Egyptian military that sends significant quantities despite Egypt’s opposition to Hamas. Companies from Turkey, a perennial champion of Palestinian rights, have entered the Israeli market with cheap cement that today is even being used to build a concrete wall around Gaza. And the UN, once broadly trusted as a neutral force, has been put on the defensive as Palestinians increasingly perceive it as an enforcer of Israeli policy via the GRM.

The GRM rules are strict, and punishments for even minor violations can put contractors and suppliers out of business for weeks or months. At al-Assar’s sun-baked plant, wedged between watermelon fields and an abandoned gas station south of Gaza City, clerks must log every 50-kilogram (110-pound) sack that comes in the gate. Walking through the rebuilt factory, al-Assar points out the dozen or so security cameras he had to install—on the front gate, on the storage shed, by the truck lot, on a light pole overlooking piles of gravel. Inside he curses as he passes two video-monitoring systems that run 24 hours a day. In Gaza, the only thing reliable about the electricity is frequent blackouts, so he had to buy a pair of battery backups to ensure a steady stream of power; if the lights go out, the internet connection fails, or a storm knocks out a camera, he risks being shut down under GRM rules. Flipping through a book of permits and receipts he must show UN inspectors anytime he makes concrete, al-Assar says the restrictions amount to “a new occupation of Gaza.”

Under the GRM, proposed projects require documents describing what will be built, for what purpose, and the quantities of materials that will be needed. That’s uploaded via a website to Israeli and Palestinian Authority officials, who check it for accuracy. When a project is greenlighted, the owner of the building gets a permit to purchase cement. At an approved store in Gaza, the buyer presents his ID and orders the material. Then he arranges transportation—typically a couple of palettes with a ton or more of cement in 50kg bags—to a concrete factory such as al-Assar’s.

In a barren upstairs office, two UN inspectors sit around smoking hand-rolled cigarettes, waiting for the grinding equipment to kick into gear. When al-Assar wants to make a batch of concrete, they scrutinize the paperwork and approve the blending of the cement with sand, gravel, and water. “The engineers stick their nose into every tiny corner of your business,” says al-Assar, who says he’s been shut down more times than he can remember. “How much concrete, where it’s going, the license number of the truck, the driver—on and on and on.”

Israel contends the restrictions are needed to rein in militants affiliated with Hamas, which has controlled Gaza since elections in 2006. After the vote, most of the international community cut off aid to Gaza, and Israel moved to isolate the territory, including a ban on sales of cement. Hamas, which long advocated the destruction of Israel, is widely known to have constructed a concrete-lined labyrinth beneath Gaza to store munitions and provide shelter for its fighters. And it built some 30 tunnels—also concrete—into Israel. On six occasions, armed men managed to get under the border, where they killed 24 Israeli soldiers and kidnapped three others. And Israel says Gaza militants have used metal, fertilizer, and even everyday household items such as ammonia and sugar to build homemade rockets that they launch at Israeli towns and cities. After militants murdered a trio of Israeli teenagers in 2014, Israel launched what it calls “Operation Protective Edge,” the third such conflict in a half-dozen years. “There is no more just war than this one,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said as the bombs fell in the summer of 2014. “We will not complete the operation without neutralizing the tunnels, the sole purpose of which is the destruction of our civilians and the killing of our children.”

Gaza’s 1.9 million residents long had a standard of living higher than in Palestinian areas of the West Bank. In the 1980s and ’90s, many Gazans commuted daily into Israel for work, and Palestinians abroad invested in projects aimed at making the territory’s wide, sandy beaches a tourist destination. The framers of the 1994 Oslo Accord even envisioned the 25-mile-long sliver of land along the Mediterranean as a Hong Kong or Singapore of the Middle East. But around 2000, after the start of the Second Intifada—the Palestinian uprising punctuated by a wave of suicide bombings in Israel—the Israelis began cutting off access to Gaza.

The economy has been in a tailspin since 2013, when Egypt started shutting down the 1,000-plus tunnels used to smuggle everything from cigarettes and chocolate to cars and cement into Gaza. In recent months, the situation has deteriorated as tensions between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, combined with continuing disagreements with Israel, have sharply curtailed money transfers into the territory. The roads are potholed and rutted. The wastewater plant is overloaded, so it often dumps raw sewage into the waters along the beach. The number of Palestinians dependent on food aid from the UN has increased to almost 1 million, compared with about 80,000 in 2000. Unemployment stands above 50%, and among young people it’s almost 70%. At midmorning, the streets are eerily empty. Few people have any reason to get out of bed.

The GRM was conceived as a temporary measure; five years later it’s still in place, and there’s growing pressure to reconsider the system and Israel’s controls on dual-use goods. The World Bank says that difficulties getting approvals for supply shipments have slowed construction of a water treatment plant by at least four years and that relaxing the dual-use limits could boost the Gaza economy 11% by 2025. If anything comes of the Trump administration’s so-called Deal of the Century to promote investment and eventually peace in the region, there will be even greater need for a more streamlined approach.

“Israel has monopolized the reconstruction”

In January, the UN, the Palestinian Authority, and the Israelis agreed to modifications aimed at making the GRM more transparent. Gazans who are sanctioned under the system or whose plans are rejected can now lodge an appeal. Projects must be approved or blocked within 45 days (before there was no time limit, and a response sometimes took months). And there’s a clear catalog of dual-use goods, making it easier for Palestinians to know what they can and can’t request. The UN says that since the changes, the average time for a decision on dual-use shipments has been cut in half, to 18 days. “It’s much more user-friendly, transparent for donors and beneficiaries, and accountable,” says Nickolay Mladenov, the UN special coordinator for the Middle East peace process.

For many Palestinians, the pain of the restrictions is compounded by the source of the materials. Although the GRM doesn’t require purchases from Israel—as many in Gaza believe—most goods pass through the country, giving its companies a strong advantage. Mohamad Abu Qammar, who sells goldfinches and canaries from his ground-floor apartment a few hundred yards from the Israeli border fence, felt he had little choice but to buy his supplies from the same people who destroyed his home.

Early in the 2014 war, most of his neighbors decamped for safer ground, but Abu Qammar had no place else to go, and he figured the Israelis would only attack militants, not civilians. Then two weeks into the conflict, his building was hit by a shell. Abu Qammar, his wife, and five children were taken to a hospital, where they were treated and released the following day. The family moved to a UN shelter, where they would stay for the next six weeks. When Abu Qammar finally got back to his home, it was still standing, but barely. He cleared away the rubble and moved back in to the damaged flat. A year and a half ago, the UN showed up with plans to rebuild. He’s happy with the reconstruction—there’s room for his songbird shop—but it stings that it was done with Israeli materials. “Israel is destroying,” Abu Qammar says, sitting in the shade of the building on a hot summer afternoon with a circle of friends, repairing a broken fan, “and Arabs are paying.”

Abu Qammar’s cement came from Nesher, which for decades had a monopoly on cement production in Israel, helping build everything from kibbutzim to Tel Aviv’s Bauhaus masterpieces to the walls that divide the West Bank. In the past 20 years, though, Israel has abandoned its socialist roots, and today it needs ever more concrete for its superhighways, high-speed trains, and luxury apartment towers. With the economy booming, the government in 2015 sought to boost competition by forcing Nesher to sell off a production facility. As imports from Greece and Turkey have grown, Nesher’s market share in Israel has fallen to 55% from 85% three years ago. But in Gaza it remains dominant. “Israel has monopolized the reconstruction,” says Mkhaimar Abusada, a political science professor at Al-Azhar University in Gaza. “There’s no doubt that Nesher is making money from the rebuilding.”

Nesher had been cut off from Gaza for the better part of a decade by Israeli restrictions on cement sales there, but the GRM opened it again. With its monopoly in Israel unwinding, the company hired a former military governor of Gaza to help boost its business in the territory, which now accounts for 10% of the Israeli cement market. But Miro Amiel, Nesher’s sales chief, calls the GRM “bullshit” and says it’s created a secondary market among people with GRM IDs who charge an extra $15 per ton to buy cement and deliver it to anyone, no questions asked. That makes his cement more expensive, tilting customers toward Egypt. “Why do you think Israel is building a wall around Gaza?” Amiel says. “Nobody really knows where the cement is going.”

Fifty miles south, through the Israeli checkpoints and across the concrete wall, fence, and barbed wire surrounding Gaza, al-Assar agrees with Amiel—and says that’s why it’s time to scrap the GRM. In addition to his office at the mixing plant, he has a space up two flights of rough concrete stairs in an unfinished Gaza City building surrounded by rubble. A glass door leads to the marble-clad suite, the only occupied floor in the otherwise empty shell. Al-Assar says the incomplete building highlights the lack of materials and the economic struggles of Gazans under the GRM. “From the beginning we opposed Serry’s plan,” he says, raising his voice to be heard over the street noise pouring in through a window propped open to catch a breeze. “We knew it would destroy our economy, but in the end we had to work with it.” —With Saud Abu Ramadan

GAZA ELECTRICITY CRISIS

Wikipedia

The Gaza electricity crisis is an ongoing and growing electricity crisis faced by nearly two million citizens of the Gaza Strip, with regular power supply being provided only for a few hours a day on a rolling blackout schedule. Some Gazans use private electric generators, solar panels and uninterruptible power supply units to consume power when regular power is not available. The crisis is a result of the tensions between Hamas, who rules Gaza, and the Palestinian Authority/Fatah, who rules the West Bank over custom tax revenue, funding of Gaza, and political authority.

Power sources

As of 2017, Gaza's normal energy needs are estimated to be approximately 400–600 megawatts for full 24-hour supply to all residents, which are normally supplied by a diesel power plant in Gaza with has a nominal rating of 60–140 MW (figures vary due to degree of operation and damage to the plant) which is reliant on fuel imports, an additional 125 MW imported from Israel via 10 power lines, and 27 MW of power imported from Egypt. Even in normal conditions, the current rated supply of Gaza is inadequate to meet growing needs, and the crisis has led to further closure and reductions to each of these power sources.

(Editor’s Note

Gaza Electricity Needs 600MW

but only 51% is installed to meet needs

140 + 125 + 27 = 292MW giving a supply shortage of 308MW)

Development

Prior to June 2013, fuel for the power plant was smuggled from Egypt, where fuel at the time was highly subsidized. Following measures taken by the Egyptians against the Gaza Strip smuggling tunnels, these cheap imports were halted and the power plant began operating in a partial capacity with fuel supplied via Israel, which charges a high[clarification needed] import duty. Even though Gaza is ruled by Hamas, they are currently dependent on the Palestinian Authority to help provide electricity – the import duties on Gaza's fuel purchases via Israel are passed to the PA, making Hamas reliant on the PA for funding, and the PA, not Hamas, pays the bill to Israel and Egypt for the electricity they provide to Gaza. As of 2017, the Palestine Authority has ceased making some of the payments.

Israeli human rights group B'Tselem has documented how common people cope in Gaza with electricity being provided on a rolling blackout schedule of a few hours a day, and has further said that Israel should take responsibility for the crisis, a responsibility Israel denies, saying that Hamas should allocate funds for electricity rather than personal gain and military expenditure on equipment and military tunnels.

In April 2017, Gaza's sole power plant ran out of fuel. Hamas blamed the Palestinian Authority for levying taxes on the fuel (levied by Israel as per Protocol on Economic Relations, and passed to the PA) while not passing tax revenue back to Gaza. The PA claims that the Hamas officials in Gaza are simply incapable of running the plant efficiently.

From April 2017, power supply from Egypt is reportedly not operational. According to Asharq Al-Awsat Egypt offered, in June 2017, to supply Gaza with electricity in exchange for the extradition of 17 wanted terrorists and other security demands.

Following the PA's refusal to pay for electricity in Gaza and instructions to reduce supply, Israel further reduced supply to Gaza in May and June 2017, saying this was an internal Palestinian matter. The Israeli military and the UN have warned that the electricity crisis and resulting humanitarian crisis may lead Gaza to initiate military hostilities. Hamas has labelled Israel's decision as "dangerous and catastrophic", threatening to renew violence.

On the 20th of June 2017, reports emerged that Egypt and Hamas reached an understanding according to which Egypt would supply 500 tons of diesel fuel daily. This supply wouldn't face Israeli custom duty rates (passed to the PA), as stipulated by the Paris Protocol, potentially placing Gaza in a separate economic bloc from Israel and the PA.

In the summer of 2017, sewage was directed untreated to the sea due to the lack of electricity, severely polluting Gaza's beaches. As a result the number of beach goers plummeted. The Israeli beach of Zikim was closed as well due to the sewage pollution from Gaza. Gazan sewage was also pumped into Israel via Nahal Hanoun from Beit Hanoun and Beit Lahia polluting the Israeli coastal groundwater aquifer.

In August 2017, the United Nations human rights office called Israel, the State of Palestinian and Hamas authorities to resolve the conflict, saying ""We are deeply concerned about the steady deterioration in the humanitarian conditions and the protection of human rights in Gaza", and that the supply of electricity for less than four a hours a day since April "has a grave impact on the provision of essential health, water and sanitation services"

GAZA’S ELECTRICITY CRISIS

Midnight rush for power in electricity-starved Gaza

Residents of Hamas-controlled enclave forced to cook, do laundry, recharge phones and computers with only 3-4 hours of power a day

Times of Israel, by MAI YAGHI, 30 August 2017

GAZA CITY (AFP) Once a day, the electricity comes on and the Ahmed household whirs into action — even if it’s the middle of the night.

Niveen starts the washing machine, her youngest son plugs in all the phones and computers to charge, her daughter runs to switch on the water heater, and her other son rushes to get his fix of television.

Such is life in the Gaza Strip, where residents have been receiving only three or four hours of household electricity a day.

The power can come on in the heat of the day or in the middle of the night, but whenever it does, people rush to get things done.

“Tonight the electricity came at 10 p.m. In a few days it will move to after midnight,” Niveen, 39, told AFP. “It’s no longer tolerable.”

Over the past three months, the already energy-sparse coastal enclave has seen its electricity crisis worsen.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, on his first visit to Israel and the Palestinian territories, will see the crisis for himself when he travels to Gaza on Wednesday.

A long-running feud between Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas’s Fatah and the Hamas terror group that runs the Gaza Strip, has led to further cuts in electricity supplies.

More than two million Gazans, already dealing with an Israeli blockade and a mostly closed border with Egypt, have to get by on three or four hours of power a day, in shifting and erratic cycles.

Umm Adel Zahour, 57, lives with her husband and eight children in the narrow alleys of Gaza City’s impoverished Shati refugee camp.

When power comes, no matter what time, she and her husband rush to bake bread with an electric oven.

“I used to make 200 loaves to cover the family for days, but now I can only do around 30,” she told AFP. “There is no power to keep the bread cold.”

Her husband recalls a worker who agreed to work flat-out to fix some bathroom tiles while the power was on, despite searing heat.

“He tried to use every minute of it. We are trying to take advantage of every minute,” he said.

‘Depends on electricity’

The crisis has both long and short term causes.

Israel has imposed its blockade on Gaza for a decade, arguing it needs to prevent Hamas, with whom it has fought three wars since 2008, from acquiring weapons or equipment to dig terror attack tunnels.

Israeli restrictions on imports of certain materials and equipment, as well as the blockade’s economic impact, have dramatically cut Gaza’s capacity to generate power, rights groups say.

On top of that, key infrastructure, including Gaza’s sole power station, has been severely damaged as a result of those conflicts.

In recent months, Abbas, based in the West Bank, has also sought to squeeze Gaza in order to isolate longtime rival party Hamas.

Abbas has reduced the amount of electricity the Palestinian Authority pays Israel to deliver to Gaza, pushing already limited electricity supplies to as little as two hours a day.

Despite Egypt in July beginning to import fuel into Gaza to help supply the Strip’s sole power station, the shortages remain severe.

While richer Gazans pay for private generators, many cannot afford to do so.

Gaza has 45 percent unemployment and more than two-thirds of the population rely on humanitarian aid.

Mahmoud al-Balawi, who owns a launderette west of Gaza City, has long given up the idea of choosing when he works.

On one recent morning, he arrived at work at 3 a.m., as that was when the power was due to come on.

“I have a lot of clothes for my customers. I want to protect my livelihood but it depends on electricity,” he said.

“Last Friday I was with my family far away but my neighbors called to tell me the power had come at an unexpected time. I left them and went to the shop.”

(FILES) This file photo taken on July 24, 2017 shows a Palestinian tailor using a sewing machine while an assistant irons a shirt during the few hours of mains electricity supply the residents of the Gaza Strip receive every day, in Gaza City. / AFP PHOTO / MAHMUD HAMS

Balawi’s company sometimes pays to run a private generator but that entails huge extra expenses.

“It’s a cost that needs to be borne by my customers but most of them won’t accept it,” he said.

Abdullah Zaqout, also from the Shati refugee camp, has to pay for electricity to look after his sick 67-year-old father, who suffers from severe asthma.

The family need constant electricity to run his nebulizer, a kind of inhaler he uses to take his medicine.

“He needs treatment every two hours. I had to invest in a private generator.”

GAZA TO PUMP SEWAGE STRAIGHT INTO SEA

Gaza municipalities threaten to pump sewage into the sea after Hamas refuses to allocate electricity for sewage treatment plants.

Arutz Sheva 7, Arutz Sheva Staff, 22/02/18

Municipalities in Gaza announced Wednesday they will pump sewage straight into the sea

due to fuel shortages and the humanitarian situation in the Hamas-controlled area.

"The beaches of the Gaza Strip will be completely closed and sewage will be pumped into the sea because the municipalities are unable to provide fuel" for treatment plants, Gaza City Municipality Head Nizar Hejazi said.

Hejazi also noted "the policy of collective punishment (which) continues to be imposed on the population," in a statement representing municipalities across Gaza.

"We announce a state of emergency in the cities and municipalities of the Gaza Strip," Hejazi said, noting services would be cut by as much as 50 percent.

The only power plant in Gaza stopped operating last week due to lack of fuel, leaving the strip totally reliant on imports.

This is not the first time Gaza is threatening to pollute international waters. For decades, Gaza’s inadequate waste treatment system has been a burden both to Gaza residents and neighboring countries on the Mediterranean coast. The area's waste treatment plant, built with $100 million of foreign aid, has been largely inactive due to Hamas' refusal to allocate electricity to operate the facility.

Instead, the terror group simply allows raw waste to dump into the Mediterranean or seep into the ground, polluting underground aquifers and harming the local water supply.

In turn, the Gazan waste has at times forced Israel to close its desalinization plant in Ashkelon, an important asset in Israel’s water supply. And Hamas themselves refuse to allow the construction of a desalination plant for Gaza's citizens.

Hamas leaders enjoy electricity 24 hours a day. However, Gaza's other residents currently receive electricity for only a few hours power per day, a situation for which they blame Hamas and the Palestinian Authority.

Earlier this month, US Special Envoy to the Middle East Jason Greenblatt slammed Hamas for investing in efforts to destroy Israel instead of in efforts to better the lives of Gaza's citizens.

"Hamas should be improving the lives of those it purports to govern, but instead chooses to increase violence and cause misery for the people of Gaza. Imagine what the people of Gaza could do with the $100 million Iran gives Hamas annually that Hamas uses for weapons and tunnels to attack Israel!" he tweeted.

Last month the United Nations envoy warned the enclave was on the verge of "full collapse."

Go to Israel to supply electricity to Gaza sewage treatment facility

The municipalities of the Gaza Strip reduce their services to half and completely close the Gaza Sea (Palestine Today 21 February 2018)

EUROPEAN COURT KEEPS HAMAS ON TERROR LIST

Poliico by Sam Safed 7/26/17

Europe’s top court ruled Wednesday that Hamas, the Palestinian militant group, should remain on a European list of terror organizations.

A lower court had removed Hamas and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a Sri Lankan militant group, from the terror list in 2014, arguing that the media and the internet were not sufficient sources upon which to base a decision. The EU appealed against that decision.

On Wednesday, the European Court of Justice overturned that ruling, arguing that media reports were a valid source upon which to make a decision. The lower court “should not have annulled Hamas’ retention on the European list of terrorist organizations,” the ECJ said.

PALESTINIAN ROCKET ATTACKS ON ISRAEL

Wikipedia

Since 2001, Palestinian militants have launched thousands[1][2][3][4] of rocket and mortar attacks on Israel from the Gaza Strip as part of the continuing Arab–Israeli conflict. From 2004 to 2014, these attacks have killed 27 Israeli civilians, 5 foreign nationals, 5 IDF soldiers, and at least 11 Palestinians[5] and injured more than 1900 people,[citation needed] but their main effect is their creation of widespread psychological trauma and disruption of daily life among the Israeli populace.[6] Medical studies in Sderot, the Israeli city closest to the Gaza Strip, have documented a post-traumatic stress disorder incidence among young children of almost 50%, as well as high rates of depression and miscarriage.[7][8][9] A public opinion poll conducted in March 2013 found that most Palestinians do not support firing rockets at Israel from the Gaza Strip.[10] Another poll conducted in September 2014 found that 80% of Palestinians support firing rockets against Israel if it does not allow unfettered access to Gaza.[11] These rocket attacks have caused flight cancellations at Ben Gurion airport.[12]

The weapons, often generically referred to as Qassams, were initially crude and short-range, mainly affecting Sderot and other communities bordering the Gaza Strip. In 2006, more sophisticated rockets began to be deployed, reaching the larger coastal city of Ashkelon, and by early 2009 major cities Ashdod and Beersheba had been hit by Katyusha, WS-1B[13] and Grad rockets.[14] In 2012, Jerusalem and Israel's commercial center Tel Aviv were targeted with locally made "M-75" and Iranian Fajr-5 rockets, respectively,[15] and in July 2014, the northern city of Haifa was targeted for the first time.[16] A few projectiles have contained white phosphorus said to be recycled from unexploded munitions used by Israel in bombing Gaza.[17][18][19][20][21]

Attacks have been carried out by all Palestinian armed groups,[22] and, prior to the 2008–2009 Gaza War, were consistently supported by most Palestinians,[23][24][25][26] although the stated goals have been mixed. The attacks, widely condemned for targeting civilians, have been described as terrorism by United Nations, European Union and Israeli officials, and are defined as war crimes by human rights groups Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. The international community considers indiscriminate attacks on civilians and civilian structures that do not discriminate between civilians and military targets illegal under international law.[27][28]

Israeli defenses constructed specifically to deal with the weapons include fortifications for schools and bus stops as well as an alarm system named Red Color. Iron Dome, a system to intercept short-range rockets, was developed by Israel and first deployed in the spring of 2011 to protect Beersheba and Ashkelon, but officials and experts warned that it would not be completely effective. Shortly thereafter, it intercepted a Palestinian Grad rocket for the first time.[29]

In the cycle of violence, rocket attacks alternate with Israeli military actions. From the outbreak of the Al Aqsa Intifada (September 30, 2000) through March 2013, 8,749 rockets and 5,047 mortar shells were fired on Israel,[30] while Israel has conducted several military operations in the Gaza Strip, among them Operation Rainbow (2004), Operation Days of Penitence (2004), Operation Summer Rains (2006), Operation Autumn Clouds (2006), Operation Hot Winter (2008), Operation Cast Lead (2009), Operation Pillar of Defense (2012), and Operation Protective Edge (2014).

LIST OF PALESTINIAN ROCKET ATTACKS ON ISRAEL, 2018

Wikipedia

AS GAZA APPROACHES ‘FAMINE,’ ISRAEL, RATHER THAN THE WORLD, APPEARS MOST CONCERNED

Following US aid cuts from UNRWA, Palestinian residents hold near-daily protests and coastal enclave appears on brink of economic collapse

Times of israel Avi Issacharoff 26 January 2018

Residents of the Gaza Strip are growing increasingly desperate over food shortages, with some saying it’s only a matter of time before Palestinians march on the Erez crossing that straddles the border with Israel “just out of distress.”

“Gaza is heading towards famine,” a longtime friend of this reporter said. “It is only a question of time, and we will get there.”

He added, “There are already cases of families who simply don’t have anything to eat, and the UNRWA budget cuts will only make things worse” — a reference to recent US cuts to the UN Palestinian aid agency.

Recently, nearly every day has seen semi-spontaneous protests, mostly by civilians, who have no livelihood and are seeking to raise international awareness of their plight.

This week, a news agency broadcast an interview with a Khan Younis resident who was offering to sell his son, held in his arms.

“Every day his mother tells me to get him something to eat,” the man said, “and I have nothing to give him.” Behind him were dozens of residents protesting the economic situation in Gaza.

Monday and Tuesday saw general trade strikes in the Strip, perhaps born of a hope, or fantasy, that such a step would serve as a wake-up call to the world, Israel, Egypt or the Palestinian Authority.

But the world is far from being concerned with Gaza at the moment. The Strip is on the brink of economic collapse, but very few are taking an interest.

Although Gazans tend to blame Israel for their situation, it is actually the Jewish state that seems to be trying to encourage improved economic conditions.

The Palestinian Authority recently decided to renew the electricity supply to Gaza by resuming payments for power generated by Israel (now providing power to homes for six hours, followed by 12 hours of darkness).

But the decision to renew the power supply was not due to a sudden stroke of generosity by the PA. According to sources, it was the result of an ultimatum by Israel: The Jewish state warned the PA that if it didn’t renew payments for the Gaza power bill, the Israeli government would cover the costs with PA tax money it collects. Ramallah understood the message and made a public show of renewing electricity payments.

At any rate, the two additional hours of power will not do much to change the economic situation in the Strip.

It was also Israel that recently went against standard policy by approving the entry of materials into Gaza that are considered dual-purpose — that is, they could be used by Hamas to build tunnels or manufacture weaponry.

Last week, wood supplies — in the past a source of tunnel beams — were allowed in to the Strip. Before that, approval was given to supplies of cement, iron, gas, fuels, and other materials.

The general hardship, however, means these dual-purpose materials are not in very high demand. One Gaza trader said there was only a 20 percent demand for the cement that Israel allowed in.

Perhaps the most pressing problem in Gaza these days is connected to government employees, both those of Hamas and the Palestinian Authority.

For more than two months, the 45,000 Hamas officials in Gaza have not received their wages. In Hamas’s view, the PA is supposed to pay, but the PA refuses due to the terror group’s refusal to hand over control of the territory.

On top of this are the thousands of PA officials who were forced out on pension. Possibly joining them now will be the 13,000 UNRWA officials, who can apparently expect to receive only half of their wages in the coming month as a result of US cuts.

And so economic activity in Gaza has been reduced dramatically. Unemployment figures have reached some 46.6%. Over a million people — half the population –need UNRWA food packages to survive the month.

One figure that should ring alarm bells in Israel relates to the demand for goods from the Jewish state. According to Palestinian figures, over a year ago the number of trucks carrying goods into the Gaza Strip every day was around 800-1,000, whereas now that has dropped to an average of just 370. This is not because of Israeli measures, but rather because the Gazans have no money to spend.

“There were over 100,000 police clarifications because of checks that bounced,” my friend said. “Every day workers are fired in the biggest trade companies, or they close.”

Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas speaks prior to attend a EU foreign affairs council at the European Council in Brussels, January 22, 2018. (EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP)

Is there a light at the end of the tunnel? At the moment, it appears not. A reconciliation between bitter rivals Fatah and Hamas has faded (again). Hamas and the Fatah-dominated PA are still at loggerheads, separate and hostile.

Egyptian Intelligence Minister Khaled Fawzy, considered the godfather of the reconciliation process, was fired last week. The man chosen to replace him is Abbas Kamil, one of the great enemies of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt.

Or, in other words, not exactly the kind of person who sees Hamas as a strategic partner.

FROM GAZA'S ECONOMY: HOW HAMAS STAYS IN POWER,

The Washington Institute Ehud Yaari and Eyal Ofer, January 6, 2011

Since Israel's August 2005 withdrawal from the Gaza Strip, Hamas has evolved from a relatively small movement into a well-funded conglomerate. Instead of being crippled by sanctions and siege, the organization has found ways to surmount early difficulties -- such as frequent payroll delays -- and establish an effective system of governance, ever tightening its grip over its fiefdom. As a result, Hamas has been able to empower loyalists while leaving the main burden of responsibility for Gaza's 1.6 million residents to others. Unfortunately, both the Ramallah-based Palestinian Authority (PA) and international donors have tolerated this situation, effectively contributing, if indirectly, to Hamas coffers.

GAZA'S ECONOMY

Reliable data regarding Gaza's finances is very difficult to obtain. Hamas has tight lips, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) release little information, and international agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank generally aggregate Gaza and the West Bank when presenting statistics. Much of the information in this article is derived from Palestinian news reports and interviews with informed sources in Gaza; accordingly, most of the figures below - see link above - should be treated as rough approximations.)

Hamas’s budget in 2013 was more than $700 million, with $260 million earmarked to the administrative costs of running Gaza.*

To fill its coffers and fund its administrative and terrorist activities, Hamas turns to several sources: funding, weapons, and training from Iran; donations from the Palestinian global diaspora;* and fundraising activities in Western Europe and North America.*

TAXES AND THE TUNNEL ECONOMY

Hamas has spent years building a network of tunnels beneath the Gazan-Egyptian border in order to smuggle weapons and other goods. According to a 2012 Journal of Palestine Studies report, at least 160 children have died while digging the elaborate tunnel system.* The underground smuggling tunnels between Gaza and Egypt has provided Hamas with a flow of tax revenue on smuggled goods, comprising roughly $500 million of Hamas’s annual budget for Gaza of just under $900 million. The Egyptian military closed the tunnels in late 2013 after it deposed the Muslim Brotherhood government, sending Gaza into an economic crisis.*

Constructing the tunnels was not a cheap endeavor, as each tunnel is believed to have cost between $80,000 and $200,000. To pay for the tunnels’ construction, Hamas turned to Gazan-based mosques and charities, which reportedly began offering pyramid schemes to invest in the tunnels with high rates of return. The number of tunnels reportedly grew from a few dozen in 2005, with annual revenue of $30 million per year, to at least 500 by December 2008, with annual revenue of $36 million per month.*

By October 2013, Egypt claimed to have destroyed 90 percent of Gaza’s smuggling tunnels. According to Ala al-Rafati, the Hamas-appointed economy minister, the resulting losses to the Gaza economy between June and October 2013 amounted to $460 million.*

FOREIGN INVESTMENT

Iran