|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Payments to Jailed Palestinians and ‘Martyrs’ by the Palestinian AuthorityP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

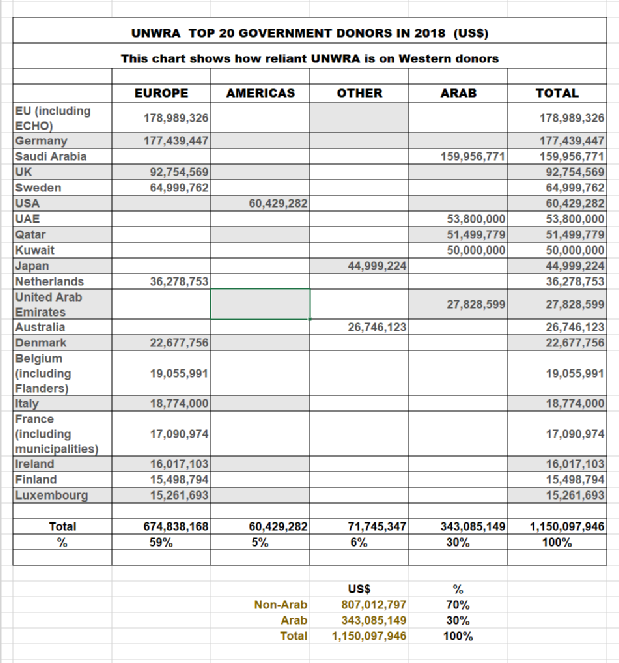

Why does such a high proportion of the UNRWA regular budget come from

Western countries and such a low proportion from Arab countries?

CREATION OF UNRWA

Wikipedia

Created in December 1949, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is a relief and human development agency which supports more than 5 million registered Palestinian refugees, and their descendants, who fled or were expelled from their homes during the 1948 Palestine war as well as those who fled or were expelled during and following the 1967 Six Day war. Originally intended to provide jobs on public works projects and direct relief, today UNRWA provides education, health care, and social services to the population it supports. Aid is provided in five areas of operation: Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem; aid for Palestinian refugees outside these five areas is provided by UNHCR.

It also provided relief to Jewish and Arab Palestine refugees inside the state of Israel following the 1948 conflict until the Israeli government took over responsibility for Jewish refugees in 1952. In the absence of a solution to the Palestine refugee problem, the General Assembly has repeatedly renewed UNRWA's mandate, most recently extending it until 30 June 2017.

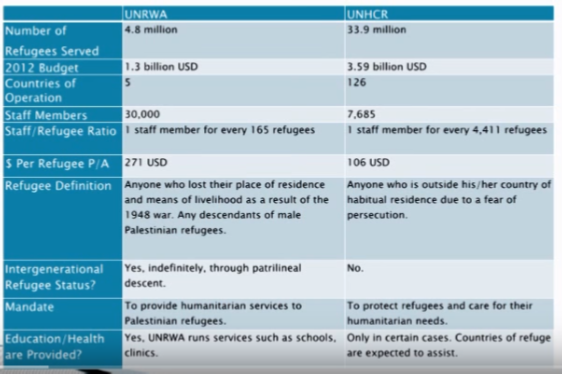

UNRWA is the only agency dedicated to helping refugees from a specific region or conflict and is separate from UNHCR. Formed in 1950, UNHCR is the main UN refugee agency, which is responsible for aiding other refugees all over the world. Unlike UNRWA, UNHCR has a specific mandate to aid its refugees to eliminate their refugee status by local integration in current country, resettlement in a third country or repatriation when possible. Only UNRWA allows refugee status to be inherited by descendants.

UNRWA has had to develop a working definition of "refugee" to allow it to provide humanitarian assistance. Its definition does not cover final status.

Palestine refugees are defined as "persons whose regular place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict."

UNRWA services are available to all those living in its area of operations who meet this definition, who are registered with the Agency, and who need assistance. The descendants of Palestine refugee males, including adopted children, are also eligible for registration as refugees. When the Agency began operations in 1950, it was responding to the needs of about 750,000 Palestine refugees. Today, some 5 million Palestine refugees are registered as eligible for UNRWA service.

UNRWA AND THE JEWS

Jewish News, Lyn Julius, Sep 2, 2018

Lyn Julius is the author of ‘Uprooted:

How 3000 years of Jewish civilisation in the Arab world vanished overnight' (Vallentine Mitchell)

Jewish refugees fleeing areas conquered by the Arab Legion in 1948. Some 3,000 Jews fled East Jerusalem.

The news that the US is no longer funding UNRWA (the UN Relief and Relief Agency) should remove one of the major obstacles to settling the conflict between Israel and the Arabs. UNRWA has been perpetuating the delusion that the Palestinians are in transit to their permanent home in Israel and that one day they will return. If the ‘refugees’ come under the umbrella of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the focus will be on rehabilitation and resettlement in their host countries.

It is not generally known that UNRWA was established with the aim of helping refugees on both sides of the conflict.

According to Don Peretz (Who is a Refugee?) initially UNRWA defined a refugee “as a needy person who, as a result of the war in Palestine, has lost his home and his means of livelihood.” This definition included some 17,000 Jews who had lived in areas of Palestine taken over by Arab forces during the 1948 war and about 50,000 Arabs living within Israel’s armistice frontiers. Israel took responsibility for these individuals, and by 1950 (Wikipedia 1952) they were removed from the UNRWA rolls leaving only Palestine Arabs and a few hundred non-Arab Christian Palestinians outside Israel in UNRWA’s refugee category.

At the time there was no internationally recognised definition of what constituted a refugee. In 1951, The UN Refugee Convention agreed the following definition:

“A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”

This definition certainly applies to the 850,000 Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Arab countries, synagogue burnings, arrests and riots. Returning to these countries would have put – and still does -their lives at risk.

The burden of rehabilitating and resettling the 650,000 Jewish refugees who arrived in Israel was shouldered by the Jewish Agency and US Jewish relief organisations, such as the Joint Distribution Committee. They were shunted into transit camps or ma’abarot. The conditions were appalling.

From an early stage in the conflict, the UN was co-opted by the powerful Arab-Muslim voting bloc to skew its mandate and defend the rights of only one refugee population – the Palestinians. The UN dedicated an agency, UNRWA, to the exclusive care of Palestinian refugees.There are ten UN agencies solely concerned with Palestinian refugees. These even define refugee status for the Palestinians explicitly: one that stipulates that status depends on ‘two years’ residence’ in Palestine.The definition makes no mention of ‘fear of persecution’ nor of resettlement. Palestinian refugees are the only refugee population in the world, out of 65 million recognised refugees, permitted to pass on their refugee status to succeeding generations, even if they enjoy citizenship in their adoptive countries. It is estimated that the current population of Palestinian ‘refugees’ is 5,493, million. Instead of resettlement, they demand ‘repatriation’, an Israeli red line. (This begs the question: why would any Palestinian wish to return to an evil, ‘apartheid’ Israel?)

In contrast to the $17.7 billion allocated to the Palestinian refugees, no international aid has been earmarked for Jewish refugees. The exception was a $30,000 grant in 1957 which the UN, fearing protests from its Muslim members, did not want publicised. The grant was eventually converted into a loan and paid back by the American Joint Distribution Committee, the main agency caring for Jews in distress.

Yet on two occasions the UN did determine that Jews fleeing Egypt and North Africa were bona fide refugees. In 1957, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, August Lindt, declared that the Jews of Egypt who were ‘unable or unwilling to avail themselves of the protection of the government of their nationality’ fell within his remit. In July 1967, the UNHCR recognised Jews fleeing Libya as refugees under the UNHCR mandate.

Needless to say, no Jew still defines himself as a refugee. Despite the initial hardships, they are now all full citizens of Israel and the West. As such, they are a model for the resettlement of Palestinian refugees in their host countries or in a putative state of Palestine alongside Israel.

For any peace process to be credible and enduring, the international community would be expected to address the rights of all Middle East refugees, including Jewish refugees displaced from Arab countries. Two victim populations arose out of the Arab-Israeli conflict, and the Arab leadership bears responsibility for needlessly causing both Nakbas – the Jewish and the Arab. As the human rights lawyer Irwin Cotler observes: ‘Put simply, if the Arab leadership had accepted the UN Partition Resolution of 1947, there would have been no refugees, Arab or Jewish.’

UNRWA HAS CHANGED THE DEFINITION OF REFUGEE

The U.N.'s agency for Palestinians

should stop playing word games and do its job.

Foreign Policy, Jay Sekulow, August 17, 2018

Last week, Foreign Policy published a story about Palestinian refugees that claimed I am among the “activists trying to strip Palestinians of their status.” The article obscured basic facts about the matters at hand—both my own role as a policy advocate and the questions that lawmakers in Congress are presently considering that pertain to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). I feel compelled to correct the record on both points.

This requires first understanding the legal facts. UNRWA was founded in 1949 through U.N. General Assembly Resolution 302 at the conclusion of the Arab-Israeli conflict of 1948, aiming for “the alleviation of the conditions of starvation and distress among the Palestine refugees” from that conflict. The agency defines Palestinian refugees as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict.”

In 1965, UNRWA changed the eligibility requirements to be a Palestinian refugee to include third-generation descendants, and in 1982, it extended it again, to include all descendants of Palestine refugee males, including legally adopted children, regardless of whether they had been granted citizenship elsewhere. This classification process is inconsistent with how all other refugees in the world are classified, including the definition used by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the laws concerning refugees in the United States.

Under Article I(c)(3) of the 1951 U.N. Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, a person is no longer a refugee if, for example, he or she has “acquired a new nationality, and enjoys the protection of the country of his new nationality.” UNRWA’s definition of a Palestinian refugee, which is not anchored in treaty, includes no such provision.

Last month, members of Congress introduced a bill asking that with respect to refugees under UNRWA the policy of the United States should be consistent with the definition of a refugee in the Immigration and Nationality Act, such that “derivative refugee status may only be extended to the spouse or minor child of such a refugee” and “an alien who was firmly resettled in any country is not eligible to retain refugee status.”

Foreign Policy’s article includes a claim that deserves closer scrutiny and reflects the sleight of hand often performed by UNRWA. The author writes:

“Palestinians, [Sekulow and his organization] claim, are the only refugees in the world who pass on their refugee status through the generations. The view is not shared by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and the State Department, which maintain that multiple generations of Afghan, Bhutanese, Burmese, Nepalese, Thai, Tibetan, and Somali people have been recognized as refugees.”

The clear implication of that paragraph, and the similar claims made by UNRWA, is that the laws I have cited above are wrong, that UNRWA’s definition of a refugee is consistent with the standard definition, and that in all of these cases the descendants of refugees are considered to be refugees as well. In actuality, what the article has done is to conflate two different issues.

The 1951 refugee convention has a lengthy definition of refugee that is personal: A refugee is a person who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.” In registering refugees on this basis, the UNHCR interprets the convention as requiring “family unity,” and it implements the principle by extending benefits to a refugee’s accompanying family, calling such people “derivative refugees.” Derivative refugees do not have refugee status on their own; it depends on the principal refugee. UNRWA’s definition is also personal: Palestinian refugees are “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict,” but it also registers “descendants of Palestine refugee males, including adopted children.” The status for descendants is not dependent upon accompanying the principal refugee.

Here is where the sleight of hand comes in: Of course it is possible for there to be multiple generations of refugees, if the multiple generations all fit the primary 1951 definition of a refugee. For example, if the granddaughter of a refugee is also outside the country of her nationality due to a well-founded fear of being persecuted, she too is a primary refugee. But she is not a refugee due to descent, because there is no provision for refugee status based on descent in the 1951 refugee convention or in internationally accepted practices for refugees who are not Palestinian refugees.

Those are the laws. Now, consider the broader political facts. Since the end of World War II, millions of refugees have left refugee camps and have been resettled elsewhere, including hundreds of thousands of Jewish people who were forced out of Arab countries. Many hardworking agencies have played a role in making sure that the descendants of these refugees were never refugees themselves. These agencies include the UNHCR, whose mandate is to protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integration, or resettlement to a third country.

IS UNRWA’S HEREDITARY REFUGEE STATUS

FOR PALESTINIANS UNIQUE?

EMET News Service, January 17 2019 [ Kohelet Policy Forum

Summary ... UNRWA's claim that their hereditary refugee status for Palestinians is not unique is simply untrue. There is no parallel and no precedent, even in protracted conflict situations, for the manner in which UNRWA transfers the "registered refugee" status, automatically, through the generations, while refusing to take any actions that would end this status. While UNHCR provides certain services on a case-by-case basis to the children of refugees, it does not make refugee status hereditary. This is one of many differences in UNRWA's treatment of its population from the general practices used by UNHCR. All these differences are designed by UNRWA to maximize the population counted as "Palestine Refugees" and perpetuate their status.

[The use here of the word "Palestinian(s)" is the author's choice. There are no such people as the "Palestinians".—ed]

See also below THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEES:

A CASE STUDY IN INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAUD

For almost 70 years, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) has created a unique category of "registered refugee" status — one that is automatically passed down to one's descendants. Under UNRWA's rules, the children and grandchildren of a Palestine refugee, and all their descendants thereof, are automatically considered ‘refugees from Palestine'. Amid ongoing criticism of UNRWA's role in purposefully perpetuating the Palestinian "refugee" problem, the agency has attempted to obfuscate its policy.

UNRWA has claimed that its hereditary refugee practice is not unique, and is also practiced by the main international refugee agency, UNHCR. This background paper aims to clarify this issue.

UNRWA - Redefining refugee status There are two separate UN agencies in charge of aiding refugees: the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine (UNRWA). UNRWA was established in December 1949 and UNHCR in December 1950. UNHCR is responsible for all refugees except those from Mandatory Palestine, who fall within UNRWA's exclusive jurisdiction.

The UNHCR determines refugee status based on criteria from international law, in particular, the Refugee Convention from 1951, which defines a refugee as "A person who owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it."

In certain cases, UNHCR gives refugee services — but not status — to the immediate family of a refugee but it does so in a manner that significantly differs from UNRWA's policy:

It is not automatic — it is based on a case-by-case review of whether the actual situation merits it. When it does, UNHCR gives certain services to the children of refugees. UNHCR does not automatically add the children and grandchildren of refugees to the count of refugees and does not automatically define them as refugees. Even if a child of refugees is given refugee services, the grandchild will not be eligible for status or services. UNRWA, on the other hand, automatically grants such children refugee status, resulting in exponential growth of refugee numbers.

UNHCR does not define as refugees people who acquired new citizenship. The Refugee Convention of 1951 has a cessation clause, which clearly says that a person ceases to be a refugee if he acquires a new citizenship. UNRWA acts differently: More than 2 million ‘Palestine Refugees' hold Jordanian citizenship, most of whom have been born in Jordan and have lived there their entire lives and are still called ‘refugees'. In addition, based on recent official census, probably 2/3 to 3/4 of the 1 million refugees registered by UNRWA in Lebanon and Syria have left those countries over the decades, with many acquiring citizenships of Western countries. Yet, UNRWA refuses to check their situation and take them off its registration rolls. UNHCR tracks individual refugees and takes them off its rolls as soon as they have acquired a status, such as third country citizenship, that ends their refugee status. This is another reason UNRWA's numbers never decline.

UNHCR does not define as ‘refugees' people who are internally displaced, that is, who have moved within the same territory. "Palestine refugees" living in the 'West Bank' or Gaza Strip were in fact internally displaced since they have never crossed the internationally recognized border of Mandatory Palestine. UNRWA considers these people as refugees, and their children and grandchildren, and all their descendants, as well.

UNHCR makes efforts to ensure refugees are resettled or locally integrated where they are staying, thereby ending their refugee status. UNHCR does not exclusively promote repatriation as sole solution, as UNRWA does, but also rehabilitation in country of refuge or in third countries.

Repatriation, rehabilitation and resettlement are considered equally legitimate means of ending a refugee status. They are promoted based on expediency — that is which could achieve the goal of ending the refugee status most quickly. UNRWA refuses to promote local rehabilitation and resettlement, and actually makes no effort to end the individual refugee status of the Palestinians, arguing that "it's not in its mandate". It actually is. This is the main reason that UNRWA's numbers grow exponentially whereas the numbers of refugees in other, shorter duration, protracted refugee situations, decline over time.

UNHCR's longest significant number of recorded refugees is from Afghanistan — from the early 1980s. UNHCR does not have in its records refugees that have been defined as such for 70 years. UNRWA does. Such persistence of refugee status has no parallel.

UNRWA reports of 5.5 million refugees. These are the descendants of roughly 700,000 registered Palestine refugees from the war of 1948. These numbers include more than 2 million ‘refugees' who hold Jordanian citizenship. They also include a larger number of ‘refugees' who live in the 'West Bank' and Gaza strip: They are citizens of the ‘Palestinian Authority' or ‘State of Palestine' and at the same time claim to be ‘refugees from Palestine'.

According to the rules applied by UNHCR, these people are not refugees.

UNRWA's claim that their policy is identical to UNHCR's is a lie and shows that they are not a neutral humanitarian organization but rather a political actor aimed at perpetuating the Palestinian refugee problem.

See also ‘The MiddleEast Piece - What is UNRWA?’

SEMI-STATE

fanak, Chronicle of the Middle East and North Africa

In retrospect, UNRWA is the only UN agency to have worked for such a long time in the exclusive service of one particular category of refugees – the ‘Palestine refugees’. Over the years, it has gradually established itself as a semi-state institution in the fullest sense, taking on responsibilities traditionally assigned to national governments. Its staff, the vast majority of whom come from the refugee communities, has grown fivefold since 1951, from about six thousand to 30,000 in 2009. However, UNRWA’s linkage with the refugees is only predicated on humanitarian considerations. Its definition of a ‘Palestine refugee’ was elaborated for operational purposes only. It did not determine who is a Palestinian refugee, but rather who is eligible for its assistance programs. While it has evolved over time, its core elements have remained the same: normal place of residence in Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and loss of means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict. Descendents of male Palestine refugees have also been eligible to register on a voluntary basis with UNRWA. Since 1951, the number of ‘Palestine refugees’ has increased fivefold, from 876,000 refugees to 4.7 million refugees in 2008. This represents about 90.8 percent of the total number of refugees in the Middle East; and about three-quarters of the estimated total Palestinian refugee population disseminated around the world.

From the outset, UNRWA’s assistance mandate has been regarded by the refugees not just as a temporary international charity venture, but as an entitlement and, even more, a recognition by the international community of their status as refugees endowed with vested rights, namely the right of return to Palestine and/or to receive compensation as recommended in UNGA resolution 194 (III) (11 December 1948). UNRWA’s identification with the political dimensions of the Palestinian refugee issue may have been reinforced by its status as the only significant UN stakeholder in charge of Palestinian refugee affairs, following the de facto demise of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) in the early 1950s , and the de jure exclusion of the Palestinian refugees from the UNHCR coverage. As a result, although registration with UNRWA was never officially meant to have any political implications, it has nevertheless been regarded by the refugees as a legal justification for their vested humanitarian and political rights. This is understandable since the ‘registration card’ it provides has constituted an official – and often unique – piece of documentary evidence attesting to their link with pre-1948 Palestine.

UNRWA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 - GAZA

UNRWA

ThIs report describes the current situation for each area. As an example their Gaza report is reproduced below.

The Gaza Strip is home to a population of approximately 1.9 million people, including 1.3 million Palestine refugees.

For the last decade, the socioeconomic situation in Gaza has been in steady decline. The blockade on land, air and sea imposed by Israel following the Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip in 2007, entered its 10th year in June 2016 and continues to have a devastating effect as access to markets and people’s movement to and from the Gaza Strip remain severely restricted.

Years of conflict and blockade have left 80 per cent of the population dependent on international assistance. The economy and its capacity to create jobs have been devastated, resulting in the impoverishment and de-development of a highly skilled and well-educated society. The average unemployment rate is well over 41 per cent – one of the highest in the world, according to the World Bank. The number of Palestine refugees relying on UNRWA for food aid has increased from fewer than 80,000 in 2000 to almost one million today.

Over half a million Palestine refugees in Gaza live in the eight recognized Palestine refugee camps, which have one of the highest population densities in te world.

Operating through approximately 12,500 staff in over 300 installations across the Gaza Strip, UNRWA delivers education, health and mental health care, relief and social services, microcredit and emergency assistance to registered Palestine refugees.

On 7 July 2014, a humanitarian emergency was declared by UNRWA in the Gaza Strip, following a severe escalation in hostilities, involving intense Israeli aerial and navy bombardment and Palestinian rocket fire. Hostilities de-escalated following an open-ended ceasefire which entered into force on 26 August 2014. The scale of human loss, destruction, devastation and displacement caused by this third conflict within seven years was catastrophic, unprecedented and unparalleled in Gaza.

UNRWA mounted an extraordinary response during the 50 days of hostilities which highlighted its unique position as the largest UN organization in the Gaza Strip and the only UN Agency that undertakes direct implementation.

The human, social and economic costs of the last hostilities are sit against a backdrop of a society already torn by wide-spread poverty, frustration and anger, heightening vulnerability and political instability. The compounded effects of the blockade and repeated armed conflicts and violence have also had a less visible, but quite profound, psychological impact on the people of Gaza. Among Palestine refugee children, UNRWA estimates that a minimum of 30 per cent require some form of structured psychosocial intervention. Their most common symptoms are: nightmares, eating disorders, intense fear, bed wetting.

In recent years, UNRWA has made significant improvements to its services in Gaza, such as its schools of excellence and excellent health services initiatives. It also better targets its assistance to the poorest of the poor through the implementation of a proxy-means tested poverty survey. UNRWA continues to:

- Improve the academic achievement, behaviour and values of school students

- Construct desperately needed infrastructure, including schools and shelters

- Improve the quality and targeting of its food and cash assistance to the poorest of the poor

- Promote gender equality and human rights for all

- Nurture entrepreneurship by supporting the private sector

- Facts & Figures

- 1.3 million registered refugees out of 1.9 million total population

- (approximately 70 per cent)

- 58 refugee camps

- Almost 12,500 staff

- 267 schools for over 262,000 students

- 21 health centres

- 16 relief and social services offices

- 3 micro-finance offices

- 12 food distribution centres for almost 1,000,000 beneficiaries.

____________________________________________

UNHCR

(THE OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES

(ALSO KNOWN AS THE UN REFUGEE AGENCY)

Wikipedia

UNHCR was established on 14 December 1950 and succeeded the earlier United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The agency is mandated to lead and co-ordinate international action to protect refugees and resolve refugee problems worldwide. Its primary purpose is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees. It strives to ensure that everyone can exercise the right to seek asylum and find safe refuge in another state, with the option to return home voluntarily, integrate locally or to resettle in a third country.

UNHCR's mandate has gradually been expanded to include protecting and providing humanitarian assistance to whom it describes as other persons "of concern," including internally displaced persons (IDPs) who would fit the legal definition of a refugee under the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and 1967 Protocol, the 1969 Organization for African Unity Convention, or some other treaty if they left their country, but who presently remain in their country of origin. UNHCR presently has major missions in Lebanon, South Sudan, Chad/Darfur, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Afghanistan as well as Kenya to assist and provide services to IDPs and refugees in camps and in urban settings.

UNHCR maintains a database of refugee information, ProGres, which was created during the Kosovo War in the 1990s. The database today contains data on over 11 million refugees, or about 11% of all displaced persons globally. The database contains biometric data, including fingerprints and iris scans and is used to determine aid distribution for recipients.The results of using biometric verification has been successful. When introduced in Kenyan refugee camps of Kakuma and Dadaab in the year 2013, the UN World Food Programme was able to eliminate $1.4m in waste and fraud.

To achieve its mandate, the UNHCR engaged in activities both in the countries of interest and in countries with donors. For example, the UNHCR hosts expert roundtables to discuss issues of concern to the international refugee community.

A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. Most likely, they cannot return home or are afraid to do so. War and ethnic, tribal and religious violence are leading causes of refugees fleeing their countries.

By the end of 2016, 65.6 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations. That was an increase of 300,000 people over the previous year, and the world’s forcibly displaced population

remained at a record high.

65.6 MILLION FORCIBLY DISPLACED WORLDWIDE

as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, or human rights violations

22.5 million people who were refugees at end-2016

17.2 million under UNHCR’s mandate

5.3 million Palestinian refugees registered by UNRWA

40.3 million internally displaced people

2.8 million asylum-seekers

10.3 MILLION NEWLY DISPLACED

During the year, 10.3 million people were newly displaced by conflict or persecution.

This included 6.9 million individuals displaced within the borders of their own countries

and 3.4 million new refugees and new asylum-seekers.

20 NEW DISPLACEMENTS EVERY MINUTE

The number of new displacements was equivalent

to 20 people being forced to flee their homes

every minute of 2016, or 28,300 every day.

10 MILLION PEOPLE

UNHCR estimated that at least 10 million people were stateless

or at risk of statelessness in 2016.

However, data captured by governments and reported to UNHCR

were limited to 3.2 million stateless individuals in 75 countries.

51% CHILDREN

Children below 18 years of age constituted about half of the refugee population

in 2016, as in recent years.

Children make up an estimated 31 per cent of the total world population.

84% HOSTED BY DEVELOPING REGIONS

Developing regions hosted 84 per cent of the world’s refugees under UNHCR’s mandate,

with about 14.5 million people.

The least developed countries provided asylum to a growing proportion,

with 28 per cent of the global total (4.9 million refugees).

552,200 REFUGEES RETURNED

Refugee returns increased from recent years.

During 2016, 552,200 refugees returned to their countries of origin,

often in less than ideal conditions. T

he number is more than double the previous year and most returned to Afghanistan (384,000).

1 IN 6 PEOPLE A REFUGEE IN LEBANON

Lebanon continued to host the largest number of refugees relative to its national population, where 1 in 6 people was a refugee.

Jordan (1 in 11) and Turkey (1 in 28) ranked second and third, respectively.

55% FROM THREE COUNTRIES

Altogether, more than half (55 per cent) of all refugees worldwide

came from just three countries:

Syrian Arab Republic (5.5 million)

Afghanistan (2.5 million)

South Sudan (1.4 million)

2.9 MILLION PEOPLE HOSTED BY TURKEY

For the third consecutive year,

Turkey hosted the largest number of refugees worldwide, with 2.9 million people.

It was followed by Pakistan (1.4 million), Lebanon (1.0 million),

the Islamic Republic of Iran (979,400), Uganda (940,800), and Ethiopia (791,600).

2.0 MILLION NEW ASYLUM CLAIMS

The number of new asylum claims remained high at 2.0 million.

With 722,400 such claims, Germany was the world’s largest recipient

of new individual applications,

followed by the United States of America (262,000), Italy (123,000), and Turkey (78,600).

189,300 REFUGEES FOR RESETTLEMENT

In 2016, UNHCR referred 162,600 refugees to States for resettlement.

According to government statistics, 37 countries admitted 189,300 refugees for resettlement during the year, including those resettled with UNHCR’s assistance.

The United States of America admitted the highest number (96,900).

75,000 UNACCOMPANIED OR SEPARATED CHILDREN

Unaccompanied or separated children – mainly Afghans, and Syrians –

lodged some 75,000 asylum applications in 70 countries during the year,

although this figure is assumed to be an underestimate.

Germany received the highest number of these applications (35,900).

SOUTH SUDAN

The fastest-growing refugee population was spurred by the crisis in South Sudan.

This group grew by 64 per cent during the second half of 2016

from 854,100 to over 1.4 million, the majority of whom were children.

SYRIA

More than half of the Syrian population lived in displacement in 2016,

either displaced across borders or within their own borders.

THE UNITED NATIONS AND THE PALESTINIAN REFUGEES:

A CASE STUDY IN INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAUD

The Times of Israel, James Cooper, November 29 2017

James Cooper is a practicing lawyer in the Greater Toronto Area.

What if you discovered that the overwhelming majority of Palestinian refugees never actually left Palestine in 1948, that they just evacuated from those portions of Mandate Palestine which constituted the frontline in what was promised to be a war of extermination of the Jewish population that lived within the confines of the war zone?

What if you found out that, in the vast majority of cases, those refugees did not scatter across the world or settle hundreds of miles from the land in which they were born? What if the truth was that in many cases, masses of those alleged refugees relocated tens of miles from their original homes, living not amidst any foreign majority population, but rather in territories where they constituted the majority and yet refused to exercise – or to demand – any kind of sovereignty for themselves?

What you are about to learn is the chronicle of an international legal fraud that has been perpetrated over the course of seven decades. The main financier and facilitator of this fraud is the institution known as the United Nations, specifically conducted through its member nations and through the offices of one of its constituent bodies, known as the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA).

In 1948, an estimated 800,000 Palestinians evacuated the contested portions of Mandate Palestine, having summoned in five neighboring Arab armies to exterminate the 600,000 Jewish residents living amid the frontlines that would eventually be bounded by the armistice borders of the State of Israel.

According to the UNRWA’s website (unrwa.org), there are currently 5 million people registered as Palestinian refugees, among whom 1.5 million live in 58 refugee camps aided by UNRWA, spread throughout the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and East Jerusalem (yes, there are Palestinian “refugees” in Jerusalem).

Most of the original cohort of 1948 Palestinian refugees are no longer alive. The burgeoning population of Palestinian refugees you see today are the descendants of that original cohort – mostly third or fourth generation refugees, the world’s only case of long-term, intergenerational refugee status inheritance.

If you thought that, to be counted as a Palestinian refugee, one must live in a refugee camp, you are mistaken. According to the UNRWA’s own figures, only 30% of Palestinian refugees actually live in what the UNRWA liberally denotes as “camps”, but which are more accurately described as UN-supported shantytowns. The rest – 70% – live outside those “camps”, overwhelmingly under the sovereignty and de facto governance of fellow Palestinians.

The UNRWA has not been accorded any legal capacity to determine who is a Palestinian refugee under international law. As a relief and aid agency, the UNRWA has its own particular definition as to who is eligible to receive UNRWA-funded services, whether in the camps themselves or anywhere else where UNRWA operates, including East Jerusalem.

The UNRWA defines Palestinian refugees as “persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and who lost both home and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict” – in other words, applicable to any Arab resident who lived in Palestine at any time less than two years before the creation of the State of Israel, whether they had resided in Palestine as a recent migrant worker or as a resident with deep ancestral ties to the land.

According to the UNRWA, any descendant of a Palestinian male refugee – and their adopted children – are eligible to be registered as refugees for the purposes of receiving UNRWA aid services. Presumably, a Palestinian female refugee who married a non-refugee is ineligible to have her descendants registered for UNRWA aid.

Regardless of the questionable eligibility requirements, the important point to keep in mind is that UNRWA registration lists cannot be taken as a legal census of Palestinians considered as refugees under international law. At best, it is a registrant list for persons entitled to call upon various aid services from the UNRWA.

As the UNRWA makes clear, it does not administer, police, or manage the “refugee camps” it works in. Rather, the governing host authority provides the land, police, and overall governance, while the UNRWA merely administers humanitarian aid and education services through the installations it manages within and outside the perimeters of those “camps.”

Other than paying the salaries of UNRWA’s core staff, the United Nations itself does not provide the bulk of the UNRWA’s funding. Rather, the agency is kept afloat through voluntary donations, with close to 50% of those donations provided by the American government (the largest donor), followed by the European Union. Since only Congress has the power to approve and allocate any portion of American government spending, it can be said that the operations of UNRWA are substantially underwritten by Congress and the American taxpayer.

Under international law, Palestinian refugee status is subject to the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status on Refugees (the UN Convention) , which applies the generally applicable definition of a refugee, and likewise determines the factors for the cessation of refugee status. There is, in fact, no international instrument of law that designates the UNRWA as a body competent to legally define and determine which Palestinian is or is not a refugee for the purposes of international law.

Again, to reiterate, the UNRWA is little more than the agency designated to provide aid and services to Palestinians that the UNRWA defines, according to its own peculiar criteria, as “refugees” (i.e. registrants entitled to receive UNRWA aid services).

As mandated by the 1951 UN Convention on Refugees, the agency tasked with overseeing the protection of the rest of the world’s refugees is the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR). To be clear, the UNHCR is not a judicial body in any sense of the term. Nevertheless, it provides determinations of refugee status (and the cessation of such status) in accordance with the relevant provisions of the 1951 UN Convention. Signatories to the UN Convention look to UNHCR in considering which individual, or groups, are entitled to refugee protection.

For practical reasons, UNHCR does not administer aid to Palestinians who receive such aid under the UNRWA system. A widely held myth is that UNRWA sets aside a special definition under international law for Palestinian refugees, while UNHCR applies a general definition for all other refugees. As previously noted, UNRWA is not set up to legally define which Palestinians are refugees under international law.

Another widely held myth is that UNRWA has the legal power to convey hereditary refugee status on Palestinians it considers as entitled to receive its services. Most clearly, it does not. Whether any particular Palestinian has retained or ceded their refugee status under international law is subject to factors considered by reference to the UN Convention. Under the UN Convention, as interpreted by UNHCR, a child of a refugee may acquire derivative refugee status – in a sense, inheriting the refugee status of the original refugee applicant.

However, this inter-generational refugee situation is often parsed in the context of protections accorded to coherent family units. Family unity is considered a desired goal under the refugee protection system, particularly where the aim is to maintain the services and protections of the family unit in an asylum country.

With regard to the very unique Palestinian situation, there are certain clear determinations that can be made under international law with respect to those who clearly do not have refugee status under any rudimentary analysis of the applicable UN Convention.

For instance, in the May 30, 1997 Note on Cessation Clauses, the UNHCR Standing Committee indicated,“Cessation of refugee status therefore applies when the refugee, having secured or being able to secure national protection, either of the country of origin or of another country, no longer needs international protection.”

Note that the underlying concern here is “international protection”, not necessarily repatriation to the country of origin. With respect to the Palestinian situation in Jordan – a de facto Palestinian State with 70% of the population being of Palestinian origin – the UNRWA counts over 2 million residents as “refugees”, though virtually all of them live outside of “camps” and have full rights of citizenship. By any stretch of the imagination, it must be conceded that the Palestinians in Jordan have been able to secure national protection in another country (i.e. Jordan, though this country was once part and parcel of Palestine before the East Bank portion was severed and rechristened as Transjordan).

In short, their situation has long since triggered the cessation clauses of the UN Convention. While the UNRWA may continue in its efforts to provide 2 million Jordanian citizens with aid services – and freely label them as “refugees” – their policy has absolutely no bearing or substance under international law. That removes 2 million Jordanian Palestinians from the “refugee” ledger.

Then, what about the Palestinian “refugees” in East Jerusalem? Under Israeli law, not only do they have permanent residency rights, but they also have the right to elect to take on Israeli citizenship, though most elect not to. But – and this is a key point – under any reasonable interpretation of refugee law, one cannot elect to stay a refugee, particularly when one already has access to, and the benefits of, national protection in the country in which one resides. So much for the Palestinian “refugees” in Jerusalem.

What, then, of the Gaza Strip, where the UNRWA registers roughly 70% of its residents – 1.3 million out of a population of 1.9 million – as “refugees”? According to UNRWA, there are eight refugee “camps” in Gaza, but they are more accurately termed as urban enclaves or neighbourhoods indistinguishable from any other crowded urban enclaves in Gaza. Nevertheless, the UNRWA insists on labeling these neighbourhoods as “camps”, though residents are free to stay or leave as they wish.

More problematically, from the perspective of refugee law, is the question as to whose “national protection” they are under. More than 20 years ago, the Palestinians of Gaza were governed by the Palestinian Authority as per the Oslo Accords. As of 2006, this “refugee” population has been under the “national protection” of Hamas. It may very well be the world’s only “refugee” population that fields its own missile arsenal, army, and a criminal justice system (of sorts).

According to Palestinian “Refugee” President Mahmud Abbas, 70% of the population of the Gaza Strip retains the theoretical right to “repatriate” a few miles across the border into the State of Israel. It may be the first instance in the annals of refugee law in which the bulk of the “refugee” population yearns to surrender their status as the majority population in their own country, and to seek minority status within the confines of the state next door in which they never had any citizenship. By any stretch of the imagination, the cessation clauses of the UN Convention have long since been triggered by the residents of the Gaza Strip. That removes a further 1.3 million Palestinians from the “refugee” ledger.

And now on to the West Bank, where the UNRWA has registered 775,000 “refugees”, with 25% of them spread across 19 “camps”. As the UNRWA freely admits, however, it does not run these “camps.” Rather, the responsibility for the administration and governance of these camps rests with the host authority, which just happens to be under the auspices of the Palestinian President. In other words – like their counterparts in Gaza – the “refugees” themselves serve as the hosts and administrators of their own “refugee” camps.

Under refugee law, repatriation to the original country of one’s nationality is just one option to bring about an end to one’s refugee status. Another option lies in integrating oneself into the local host population. But what if the local host population just happens to be your fellow nationals? Unless an international jurist can raise a persuasive argument that 775,000 West Bank “refugees” are unable to sufficiently integrate with themselves in the West Bank, I would argue that here is a good case for removing a further 775,000 West Bank Palestinians from the refugee ledger.

All of which leaves us – according to the UNRWA’s trustworthy figures – 450,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and around 500,000 in Syria (though those numbers have no doubt diminished substantially over the last few years, in light of the current turmoil in these countries). In terms of the UN Convention, these residents are able to present a comparatively stronger case for maintaining their legal status as refugees, or at least the need for international protection. For one thing, over the course of decades, they have formed a minority population in the midst of a majority population that otherwise disparages them and that has historically denied them full participation as citizens in line with the host residents.

With regard to the Palestinians in Syria, they remain vulnerable to the spillover of bloody civil war that has recently fragmented the country. However, when one looks closer, one must ask: Does a theoretical need for refugee protection in this instance necessarily lead to a need to repatriate the population to the country of origin, much less to the State of Israel?

As noted above, the governing concern of the UN Convention is that the refugee achieve some kind of practical protection, whether that comes from repatriation or from integration into the local host population. As of this writing, certainly the Palestinians in Syria – along with almost all Syrians, incidentally – may be considered a population in need of physical protection. Currently, the option of local integration is not practicable.

But in light of the current demography of Palestinians who reside within the borders of what formerly constituted Mandate Palestine, there are far more practical options to consider than mass settlement of Syrian and Lebanese Palestinians within the borders of the State of Israel.

Let us examine, for instance, this notion of “repatriation.” Under refugee law, there is no right to be repatriated to an ancestor’s house or neighbourhood that you had never lived in. Even with the provisional stipulation that refugee protection status can be inherited under international law, the repatriation rights of the stateless grandson cannot be equated with those of the grandfather who was forced to abandon his house and neighbourhood.

In the event the Palestinian grandson one day crossed the border from Syria into what was once Mandate Palestine, and chose to settle securely either in the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, or Jordan, his refugee status would come to an end, despite the fact that he nevertheless wished to reclaim the grandfather’s house over the border in that part of the former Palestine Mandate that now comprises the State of Israel.

In short, there is absolutely no special or intrinsic right under refugee law for any Lebanese or Syrian Palestinian to “repatriate” into the State of Israel as opposed to those areas of the former Palestine Mandate where the Palestinians effectively comprise the host population.

Even under the most generous and liberal reading of the UN Convention, a mass repatriation of such a population to the State of Israel would be discouraged and avoided on practical grounds alone. More to the point, what exactly makes the borders of the State of Israel the necessary go-to destination for an alleged Palestinian refugee?

As noted, the aspiration of refugee protection law is to repatriate a refugee within their “country of origin” or among their “nationality of origin”. The Palestinians who evacuated the contested frontlines of a portion of the Palestine Mandate, which eventually became the State of Israel, cannot maintain – under any principle of refugee law – an inherited, inter-generational right to repatriate to the same home, neighbourhood, or town once occupied by one’s ancestor.

In practice, refugee law simply does not operate on that level of particularity. Rather, the unit of international redress is the state or nationality of origin. Under refugee law, a Palestinian cannot “reacquire” Israeli nationality or citizenship rights because they never had such rights to begin with,. A “return” to your grandfather’s former house in Haifa may very well be considered as a return to the ancestral homestead, but under refugee law, it could not be considered as a “return” to your nationality of origin, particularly in a situation where your nationality of origin has subsequently coalesced as an autonomous authority elsewhere in another portion of what was once Mandate Palestine.

Thus, even when – at least for the sake of argument – one stipulates and concedes that Palestinian refugee status might be inherited, and that – after 70 years – there might exist some kind of right in refugee law for repatriation of the descendants of the original refugees, it is difficult to argue in good faith that such refugees by rights must be settled in the portion of their former “country of origin” that now comprises a foreign nationality (i.e. Israeli), rather than in the portion of their country of origin that comprises their own nationality (i.e. Palestinian).

Up to this point, I have stipulated that – as of 1948 – there exists a “nationality of origin” that one could describe as “Palestinian.” In truth, it would be anachronistic and wholly inaccurate to accept such a stipulation on its face. The 1948 invasion of Palestine by five Arab nations – in concert with the Arabs of Mandate Palestine – was premised on incorporating Palestine as part of the greater Arab nation, and was based on the ideology of pan-Arab nationalism, itself founded by the leader of the Arab community in Palestine, Haj Amin al-Husseini. .

As late as 1964, the PLO Charter defined its national goal as providing for the armed liberation of Palestine, for the express purpose of incorporating it into the greater Arab nation.

With respect to refugee law, the relevant time frame of reference is the year 1948. In short, we must look at the circumstances that existed at the time the refugee crisis first arose. At that time, all sources were consistent with the collective understanding that the Arabs of Palestine viewed themselves not as “Palestinian” in nationality, but rather as citizens of the greater Arab nation. On that basis, the armies of five neighbouring Arab states were called in by the Arab leadership of Palestine to claim all of Mandate Palestine for the greater Arab nation, in accordance with the ideology of pan-Arab nationalism.

It is a crucial – yet conceptually subtle – point – to emphasize. If, indeed, the Arabs of Palestine declared themselves as fellow belligerents and as fellow citizens, of the greater Arab nation that invaded the newly formed State of Israel in 1948, then their self-declared “nationality of origin” on this date would arguably be shared with the citizens of their fellow co-belligerents, among whom were the Jordanians, Syrians, and Lebanese. In short, all the belligerents against the newly formed State of Israel – including the Arab leadership of Mandate Palestine – declared war against the Jewish State on the basis of their shared nationality as members of the greater Arab nation, whether Sunni, Shiite, or Christian.

According to the nationalized dynamics of the conflict, the Arab nationals of one part of Mandate Palestine sought refuge among fellow Arab nationals in other portions of Mandate Palestine, and across the border with fellow Arab nationals in the neighbouring Arab states.

What set the Palestinian Arabs apart in those neighbouring Arab states was not due to any inherent cultural or ethnic differences, but rather due to the political and legal need to keep them demographically intact and isolated from the host population, so as to retain their refugee status and their political use as part of the regional toolkit in the ongoing war to bring about the collapse of the State of Israel.

A suitable frame of reference would be the mass population exchanges that accompanied the partition of Pakistan from a portion of India in 1947. Upon the creation of Pakistan, millions of Muslims were uprooted and “repatriated” into the newly created Muslim state of Pakistan, while masses of Hindu adherents were evacuated from areas that would comprise Pakistan, and “repatriated” into the Hindu majority state of India.

With respect to the India-Pakistan crisis, there has been no international call for several million Hindus to be “repatriated” back into the territories that were incorporated into the Muslim majority state of Pakistan. It would be an absurd request in any case, in light of the fact that there would be no “nationality of origin” for these Hindu residents to “reacquire” in the Muslim state of Pakistan.

So, too, with the respective Jewish and Arab populations that were displaced in the wake of the creation of the State of Israel. An estimated 800,000 Middle Eastern Jews were expelled, or fled, from various countries around the Arab world, and subsequently integrated with their fellow Jews within the State of Israel.

Over the course of decades, there has been no sustained call for the Jewish refugees of the Middle East to be repatriated back to their original homes, or to be compensated en masse. By contrast, the Arab refugees from the 1948 war were effectively “weaponized” by the Arab World as demographic cannon fodder to be employed against the State of Israel, to be held in place in refugee settlements – again, mostly within the borders of Mandate Palestine – for the sole purpose of sustaining their legal status as refugees under international law.

Thus, up until 1967, both Egypt (in the Gaza Strip) and Jordan (in both Jordan and the West Bank) opted to permanently warehouse masses of Palestinians in refugee “camps” within the borders of Mandate Palestine for no reason at all, except to preserve for them the legal option of being repatriated across the border of the State of Israel.

With the active support of the oil-rich Gulf States, and in collusion with the Soviet Union (up until 1967) – and thereafter, with the European Union – the UNRWA would serve as the educational and “humanitarian” instrument by which an intergenerational refugee population would be educationally nourished on an identity of grievance, victimhood, and, above all, a fervent desire to destroy the very state in which they were demanding to be repatriated – incidentally, an ongoing circumstance of belligerence according to which the UN Convention advises against repatriation.

After 1967, once Israel acquired the territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, an initial effort was made by the Israeli government – in its new role as the Administrative Authority in these territories – to dismantle the refugee settlements and to prod the “refugees” to integrate with the other Palestinian Arab residents of the area who weren’t registered by the UNRWA.

But the “refugees” – and the United Nations – were having none of it. So long as the UNRWA umbrella remained in place, the legal fiction could be sustained that any Palestinian Arab receiving aid by the UNRWA preserved a future ticket to settle in the State of Israel.

In time, when even the majority of Palestinians drifted out of the physical boundaries of the “camps” – which were now “camps” only in the sense that they had UNRWA installations set up within the boundaries of these designated crowded neighborhoods – the UNRWA brand was such that you no longer even needed to reside in a “camp” in order to sustain your refugee status. So long as you were registered with the UNRWA, and thus eligible to receive its services, you would be deemed a Palestinian “refugee” in the eyes of the US State Department, the European Union, and most of the other member states of the UN.

While integration into the local host community would be sufficient to end refugee status under the UNHCR system, the UNRWA umbrella remained in place – and would be repeatedly renewed by the UN – in order to artificially and indefinitely sustain Palestinian refugee status. Under the UNRWA umbrella, local integration would be wholly irrelevant in determining the end of one’s refugee status; henceforth, repatriation – into the Jewish State – would be considered as a valuable and viable bargaining chip to be placed on the table, at least so long as one was registered with UNRWA.

As we have seen, the overwhelming majority of Palestinian refugees do have a number of options available to end their refugee status. Those options, in turn, challenge the underlying rationale for refugee protection law, which is to mitigate the refugee’s vulnerable position with practical solutions.

In other words, if the refugee is presented with a viable option to improve their unfortunate circumstances, yet the refugee elects instead to maintain the status quo in order to preserve future options currently unavailable to that refugee (i.e. they want to voluntarily maintain their legal status as a refugee without triggering the cessation clauses), that stance can justifiably be viewed as insincere, as fraudulent, as evidence of bad faith conduct.

All of which brings us to the legal fraud that forms the basis of the Palestinian refugee claim. Under common law, when a party claims a personal injury, they have a duty to mitigate their losses, even while seeking redress for the alleged tort committed against them.

For seventy years, the Palestinians have claimed to suffer a grievous tort at the hands of the Jewish population they had initially sought to “throw into the sea.” Back in 1948, under international law, the newly formed State of Israel was under absolutely no legal obligation to accept a hostile population back into the domain of the once contested frontline.

By point of contrast, the Palestinians who remained within the borders of the State of Israel – after the initial cessation of hostilities in 1949 – happened to come from villages and towns where the population refrained from threatening the viability and physical safety of the newly formed state and its Jewish inhabitants. That population has since grown more than ten-fold over the course of several decades, sharing in the full rights of Israeli citizenship.

In the two decades from 1949 to 1967, the overwhelming bulk of internally displaced Palestinians continued to reside in the portions of Mandate Palestine that did not comprise the State of Israel, among a host population that was overwhelmingly Palestinian in origin. In that time frame, there was neither any plea nor request for “camp” residents to be integrated into the local host population, whether among their fellow countrymen in the West Bank, in Gaza, in Jordan, or among their fellow Arab neighbours in Syria and Lebanon.

Nor in that time frame was there any call or desire to exercise any kind of sovereign national governance over those portions of Mandate Palestine where they constituted the overwhelming majority.

f, in the case of Syria and Lebanon, the host governments made a concerted effort to maintain the minority Palestinian population in their second-class status, it is telling that no effort or request was made by these residents to resettle themselves among their “countrymen” in Gaza, the West Bank, or Jordan. On the one hand, they claimed to “suffer” on account of their extended refugee status, yet on the other hand, took every measure to ensure that they would not do anything to trigger the legal cessation of their refugee status.

In order to maintain the legal fiction of an ongoing refugee “crisis”, both the Arab World and the West – in collusion with the Soviet Union – did everything possible to ensure that Palestinian refugee “camps” would stay in place, even as they evolved into crowded urban enclaves. So long as the UNRWA would continue to offer services there and continue to designate these enclaves as “camps”, the legal fiction could continue in perpetuity.

Even as the majority of Palestinian “refugees” left the “camps” for more desirable accommodations, the remnant that chose to stay on in these “camp” /UNRWA-serviced enclaves would continue to be shown to the world as Exhibit A in the showpiece of Palestinian “suffering”.

However, lost in all this extended propaganda – even to much of the Israeli public – was this notion of Palestinian choice, of Palestinian agency, of the failure to mitigate one’s presumed injuries.

Against the evidence of that course of conduct, the incessant call for the “refugees” to repatriate en masse, from the Palestinian enclave of their portion of Palestine, into the Jewish enclave of the remaining portion, could only be seen for what it was – a strategy intended to demographically dissolve the Jewish polity within the borders of the State of Israel.

Since the signing and implementation of the Oslo Accords, the Palestinians have taken some element of sovereign control over the Gaza Strip and over significant portions of the West Bank, denoted as Areas A and B. And yet, in these areas alone, a combined total of roughly 2 million Palestinian “refugees” claim the theoretical right to leave their “country of origin”, and to settle instead within the borders of the State of Israel, to live among six million Jews as a hostile minority.

The US State Department – for the sake of “peace” – continues to underwrite the legal fiction that the Palestinians suffer a legitimate refugee “crisis” that somehow requires Israel’s participation and concessions to resolve.

In the meantime, the Palestinians continue on as history’s most astoundingly unique case study in refugee crisis management. Where other refugee populations tend to diminish in the space of a few years, this one grows inter-generationally by orders of magnitude, mostly by means of natural growth rather than through ongoing displacement. Where other refugee populations look for any viable option to get out of the camps, this one seeks out funding, services, and indoctrination activities to keep a credibly sustainable mass of their population in the camps. While most refugee populations will do anything to end their legal status as refugees, this one will do anything to keep their legal status as refugees from ending.

In recent years, the Palestinian President has presented the international community with a truly puzzling legal conundrum to work through. If, on the one hand, you intend to argue that – thanks to the Oslo Accords – you now preside over a quasi-sovereign political entity that is internationally recognized as the “State of Palestine”, then under what principle of refugee law can you credibly maintain the argument that a significant proportion of your citizens nevertheless require the “protection” of being “repatriated” to the alien state next door?

The answer: You can’t credibly maintain this legal paradox. Yet in collusion with the majority of member states that comprise the United Nations, you can fraudulently maintain the illusion that your arguments are indeed credible under international law.

|

IS UNRWA’S HEREDITARY REFUGEE STATUS FOR PALESTINIANS UNIQUE? |

|

WHAT UNHCR and UNRWA DO |

|

|

SERVE 5,300,000 PEOPLE (2016)

All field offices have a similar organizational structure and UNRWA’s programmes are implemented and managed by the: Education Department Health Department Relief and Social Services Department Department of Infrastructure and Camp Development in Amman Office of the Microfinance and Microenterprise Programme in Jerusalem. The number of area staff range from 3,000 in the Lebanon Field Office to over 10,000 in the Gaza Field Office. UNRWA has over 30,000 employees, most of them Palestinian refugees and a small number of international staff. The majority of area staff are teachers, health services, relief and social services staff and administrative and support staff In addition to area staff, the United Nations in New York funds nearly |

(10,800 EMPLOYEES - 31.12.2016)

Advocacy Asylum and Migration Cash-Based Interventions Coordinating Assistance Education Ending Statelessness Environment, Disasters and Climate Change Innovation Livelihoods Protection Public Health Safeguarding Individuals Shelter Solutions |

UNRWA and UNHCR

|

|

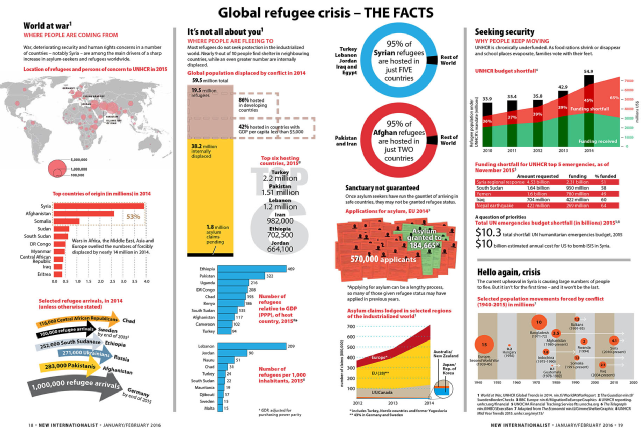

The UN |

Where people come from, where they flee to – and why they keep moving.

New Internationalist gives a worldwide context for refugee flows with this

zoomable infograph from our Jan/Feb magazine ( 1 Jan 2016).