|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

|

|

|

|

|

CLICK BUTTON |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Israel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ISRAEL - PALESTINIAN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

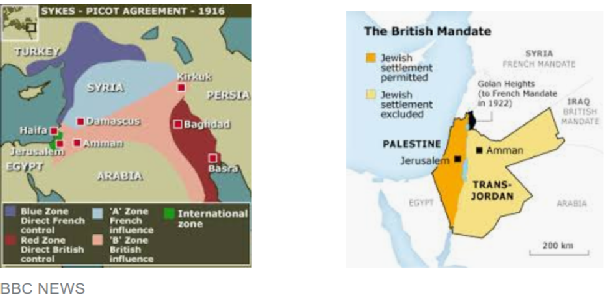

WHY BORDER LINES DRAWN WITH A RULER IN WW1

STILL ROCK THE MIDDLE EAST

BBC Tarek Osman Presenter: The Making of the Modern Arab World

14 December 2013

A map marked with crude chinagraph-pencil in the second decade of the 20th Century shows the ambition - and folly - of the 100-year old British-French plan that helped create the modern-day Middle East.

Straight lines make uncomplicated borders. Most probably that was the reason why most of the lines that Mark Sykes, representing the British government, and Francois Georges-Picot, from the French government, agreed upon in 1916 were straight ones.

Sykes and Picot were quintessential "empire men". Both were aristocrats, seasoned in colonial administration, and crucially believers in the notion that the people of the region would be better off under the European empires.

Both men also had intimate knowledge of the Middle East.

The key tenets of the agreement they had negotiated in relative haste amidst the turmoil of the World War One continue to influence the region to this day. But while Sykes-Picot's straight lines had proved significantly helpful to Britain and France in the first half of the twentieth century, their impact on the region's peoples was quite different.

The map that the two men drew divided the land that had been under Ottoman rule since the early 16th Century into new countries - and relegated these political entities to two spheres of influence:

- Iraq, Transjordan, and Palestine under British influence

- Syria and Lebanon under French influence

The two men were not mandated to redraw the borders of the Arab countries in North Africa, but the division of influence existed there as well, with Egypt under British rule, and France controlling the Maghreb.

A SECRET DEAL

But there were three problems with the geo-political order that emerged from the Sykes-Picot agreement.

First, it was secret without any Arabic knowledge, and it negated the main promise that Britain had made to the Arabs in the 1910s - that if they rebelled against the Ottomans, the fall of that empire would bring them independence.

When that independence did not materialise after World War One, and as these colonial powers, in the 1920s, 30s and 40s, continued to exert immense influence over the Arab world, the thrust of Arab politics - in North Africa and in the eastern Mediterranean - gradually but decisively shifted from building liberal constitutional governance systems (as Egypt, Syria, and Iraq had witnessed in the early decades of the 20th Century) to assertive nationalism whose main objective was getting rid of the colonialists and the ruling systems that worked with them.

This was a key factor behind the rise of the militarist regimes that had come to dominate many Arab countries from the 1950s until the 2011 Arab uprisings.

TRIBAL LINES

The second problem lay in the tendency to draw straight lines.

The newly created borders did not correspond to the actual sectarian, tribal, or ethnic distinctions on the ground

Sykes-Picot intended to divide the Levant on a sectarian basis:

- Lebanon was envisioned as a haven for Christians (especially Maronites) and Druze

- Palestine with a sizable Jewish community

- the Bekaa valley, on the border between the two countries, effectively left to Shia Muslims

- Syria with the region's largest sectarian demographic, Sunni Muslims

Geography helped.

For the period from the end of the Crusades up until the arrival of the European powers in the 19th Century, and despite the region's vibrant trading culture, the different sects effectively lived separately from each other.

But the thinking behind Sykes-Picot did not translate into practice. That meant the newly created borders did not correspond to the actual sectarian, tribal, or ethnic distinctions on the ground.

These differences were buried, first under the Arabs' struggle to eject the European powers, and later by the sweeping wave of Arab nationalism.

BRUTALITY

In the period from the late 1950s to the late 1970s, and especially during the heydays of Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser (from the Suez Crisis in 1956 to the end of the 1960s) Arab nationalism gave immense momentum to the idea that a united Arab world would dilute the socio-demographic differences between its populations.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the Arab world's strong men - for example, Hafez Assad and Saddam Hussein in the Levant and Col Muammar Gaddafi in North Africa - suppressed the differences, often using immense brutality.

But the tensions and aspirations that these differences gave rise to neither disappeared nor were diluted. When cracks started to appear in these countries - first by the gradual disappearance of these strong men, later by several Arab republics gradually becoming hereditary fiefdoms controlled by small groups of economic interests, and most recently after the 2011 uprisings - the old frictions, frustrations, and hopes that had been concealed for decades, came to the fore.

IDENTITY STRUGGLE

The third problem was that the state system that was created after the World War One has exacerbated the Arabs' failure to address the crucial dilemma they have faced over the past century and half - the identity struggle between, on one hand nationalism and secularism, and on the other, Islamism (and in some cases Christianism).

The founders of the Arab liberal age - from the late 19th Century to the 1940s - created state institutions (for example a secular constitution in Tunisia in 1861 and the beginnings of a liberal democracy in Egypt in the inter-war period), and put forward a narrative that many social groups (especially in the middle classes) supported - but failed to weave the piousness, conservatism, and religious frame of reference of their societies into the ambitious social modernisation they had led.

And despite major advancements in industrialisation, the dramatic inequity between the upper middle classes and the vast majority of the populations continued. The strong men of Arab nationalism championed - with immense popular support - a different (socialist, and at times militarist) narrative, but at the expense of civil and political freedoms.

And for the past four decades, the Arab world has lacked any national project or serious attempt at confronting the contradictions in its social fabric.

THE NEW GENERATION

That state structure was poised for explosion, and the changing demographics proved to be the trigger. Over the past four decades, the Arab world has doubled its population, to over 330 million people, two-thirds of them are under 35 years old.

This is a generation that has inherited acute socio-economic and political problems that it did not contribute to, and yet has been living its consequences - from education quality, job availability, economic prospects, to the perception of the future.

At core, the wave of Arab uprisings that commenced in 2011 is this generation's attempt at changing the consequences of the state order that began in the aftermath of World War One.

This currently unfolding transformation entails the promise of a new generation searching for a better future, and the peril of a wave of chaos that could engulf the region for several years.

The Making of the Arab World, presented by Tarek Osman, can be found on the BBC Radio 4 websiteS

A LINE IN THE SAND

Britain, France and the Struggle that Shaped the Middle East, Prologue,

James Barr, 2011

In the summer of 2007 I came across a sentence in a newly declassified British government report that made my eyes bulge. Written by an officer in the British security service, MI5, in early 1945 but never published until now, it solved a mystery that had been puzzling the government. Who was financing and arming the Jewish terrorists who were then trying to end British rule in Palestine? The officer, just back from a visit to the Middle East, provided an answer that was astonishing. The terrorists, he reported, ‘would seem to be receiving support from the French’.

Adding that he had spoken to his counterparts in Britain’s secret intelligence service, MI6, the officer continued: ‘We ... know from “Top Secret” sources that French officials in the Levant have been clandestinely selling arms to the Hagana* and we have received recent reports of their intention to stir up strife within Palestine’. In other words, while the British were fighting and dying to liberate France, their supposed allies the French were secretly backing Jewish efforts to kill British soldiers and officials in Palestine.

France’s extraordinary move marked the climax of a struggle for the control of the Middle East that had been going on for thirty years. In 1915 Britain and France, wartime allies then too, tried to resolve the tensions that their rival ambitions in the region were causing using. In the secret Sykes-Picot agreement they split the Ottomans’ Middle Eastern empire between them by a diagonal line in the sand that ran from the Mediterranean Sea coast to the mountains of the Persian frontier. Territory north of this arbitrary line would go to France; most of the land south of it would go to Britain, for the two powers could not agree over the future of Palestine. The compromise, which neither power liked, was that the Holy Land should have an international administration.

Crude empire-building of this type had been common in the nineteenth century, but it was already unpopular by the time that the Sykes-Picot agreement was signed. Chief among its critics was the American president Woodrow Wilson. When the United States declared war on Germany in 1917 he criticised European imperialism and proposed that, when the war was over, subject and stateless peoples should be able to choose their own destinies instead.

In this new atmosphere, the British urgently needed a new basis for their claim to half the Middle East. Already in control of Egypt, they quickly realised that, by publicly supporting Zionist aspirations to make Palestine a Jewish state, they could secure the exposed east flank of the Suez Canal while dodging accusations that they were land-grabbing. What seemed at the time to be an ingenious way to outmanoeuvre France has had devastating repercussions ever since.

The British knew from the outset that this move risked causing deep anger in the Muslim world, but they were confident that they could overcome it. They believed that the Arabs would recognise the economic advantages of Jewish immigration and that the Jews would long be grateful to Britain for helping them realise their dream. Both assumptions proved to be wrong. When Jewish immigration triggered Arab outrage, British attempts to keep the peace by slowing change swiftly exasperated the Jews.

Under mandates granted by the League of Nations, Britain took control of Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq; France, Lebanon and Syria. Both powers were supposed to steer these embryonic countries to rapid independence, but they immediately began to drag their feet. The Arabs reacted angrily as the freedom they had been promised continually receded before them like a mirage. The British and the French blamed one another’s policies for the opposition they each began to face. Each refused to help the other address violent Arab opposition because they knew that they would only make themselves more unpopular by doing so. For almost two years in the 1920s, the British ignored frequent French requests to stop the rebels who were fighting their forces inside Syria from using neighbouring, British-controlled, Transjordan as a base. The French in turn shrugged when the British asked them to clamp down on the Arabs who were taking sanctuary in Syria and Lebanon during their insurgency in Palestine in the second half of the 1930s. Lacking neighbourly support, both France and Britain resorted to violent tactics to crush protest that only enraged the Arabs further.

The French had long believed that the British were actively aiding Arab resistance to their rule, but up until the outbreak of the Second World War this suspicion was unfounded. The fall of France in 1940, and the subsequent decision by the French in the Levant to back the Vichy government, ended both sides’ reluctance to interfere in one another’s problems. In June 1941 British and Free French forces invaded Syria and Lebanon to stop the Vichy administration providing Germany with a springboard for an offensive against Suez. After the Vichy French surrendered a month later, the British government entrusted the government of Lebanon and Syria to the Free French. When that move caused Arab anger British officials decided that the best way to divert attention away from Palestine was to help both Syria and Lebanon gain their independence at French expense. With significant British assistance the Lebanese did so in 1943. The French found out that the British were plotting with the Syrians to the same end the following year.

The French discovered that the Zionists shared their appetite for revenge, for by now Jewish opinion had moved decisively against the British. In 1939 the British, in a bid to placate the Arabs, had imposed tight immigration restrictions that prevented large numbers of Jews fleeing Nazi Germany from reaching safety in Palestine. When news of the systematic nature and the scale of the Holocaust emerged, many Jews decided that it was time to throw the British out. Britain’s appeasement of the Arabs’ terrorism before the war had shown that violence worked. As this book reveals, the French now secretly offered support to Zionist terrorists who shared their determination to drive the British out of Palestine.

What makes this venomous rivalry between Britain and France so important is that it fuelled today’s Arab-Israeli conflict. Britain’s use of the Zionists to thwart French ambitions in the Middle East led to a dramatic escalation in tensions between the Arabs and the Jews. But it was the French who played a vital part in the creation of the state of Israel, by helping the Jews organise the large-scale immigration and devastating terrorism that finally engulfed the bankrupt British mandate in 1948. This book tries to explain how matters came to such a pass.

SYKES-PICOT AND ITS AFTERMATH –

UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES

The Sykes-Picot carve-up led to a century of turbulence

Economist May 14th 2016

This article appeared in the Special Report section of the print edition

The modern frontiers of the Arab world only vaguely resemble the blue and red grease-pencil lines secretly drawn on a map of the Levant in May 1916, at the height of the first world war. Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot were appointed by the British and French governments respectively to decide how to apportion the lands of the Ottoman empire, which had entered the war on the side of Germany and the central powers. The Russian foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, was also involved. The war was not going well at the time. The British had withdrawn from Gallipoli in January 1916 and their forces had just surrendered at the siege of Kut in Mesopotamia in April.

Still, the Allies agreed that Russia would get Istanbul, the sea passages from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean and Armenia; the British would get Basra and southern Mesopotamia; and the French a slice in the middle, including Lebanon, Syria and Cilicia (in modern-day Turkey). Palestine would be an international territory. In between the French- and British-ruled blocs, large swathes of territory, mostly desert, would be allocated to the two powers’ respective spheres of influence. Italian claims were added in 1917.

But after the defeat of the Ottomans in 1918 these lines changed markedly with the fortunes of war and diplomacy (see map). The Turks, under Kemal Pasha Ataturk, pushed foreign troops out of Anatolia. Mosul was at first apportioned to France, then claimed by Turkey and subsequently handed to Britain, which attached it to the future Iraq. One reason for the tussle was the presence of oil. Even before the war, several Arab territories—Egypt, north Africa and stretches of the Arabian Gulf—had already been parcelled off as colonies or protectorates.

Even so, Sykes-Picot has become a byword for imperial treachery. George Antonius, an Arab historian, called it a shocking document, the product of “greed allied to suspicion and so leading to stupidity”. It was, in fact, one of three separate and irreconcilable wartime commitments that Britain made to France, the Arabs and the Jews. The resulting contradictions have been causing grief ever since.

In the end the Arabs, who had been led to expect a great Hashemite kingdom ruled from Damascus, got several statelets instead. The Maronite Christians got greater Lebanon, but could not control it. The Kurds, who wanted a state for themselves, failed to get one and were split up among four countries. The Jews got a slice of Palestine.

The Hashemites, who had led an Arab revolt against the Ottomans with help from the British (notably T.E. Lawrence), were evicted from Syria by the French. They also lost their ancestral fief of the Hejaz, with its holy cities of Mecca and Medina, to Abdel Aziz bin Saud, a chieftain from the Nejd, who was backed by Britain. Together with his Wahhabi religious zealots, he founded Saudi Arabia. One branch of the Hashemites went on to rule Iraq, but the king, Faisal II, was murdered in 1958; another branch survives in a little kingdom called Transjordan, now plain Jordan, hurriedly partitioned off from Palestine by the British.

Israel, forged in war in 1948, fought and won more battles against Arab states in 1956, 1967 and 1973. But its invasion of Lebanon in 1982 was a fiasco. The Palestinians, scattered across the Middle East, fought a civil war in Jordan in 1970 and helped start the one in Lebanon in 1975. Syria intervened in 1976 and did not leave Lebanon until forced out by an uprising in 2005. More than two decades of “peace process” between Israel and Palestine, starting with the Oslo accords of 1993, have produced an unhappy archipelago of autonomous areas in the Israeli-occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip.

Morocco marched into the western Sahara when the Spanish departed in 1975. The year after Iran’s Islamic revolution of 1979, Iraq started a war that lasted eight years. It then invaded Kuwait in 1990, but was evicted by an American-led coalition.

The Suez Canal and vast oil reserves kept the region at the forefront of cold-war geopolitics. France and Britain colluded with Israel in the war against Egypt in 1956 but were forced back by America. Yet America soon became the predominant external power, acting as Israel’s main armourer and protector. After Egypt defected from the Soviet camp, America oversaw the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty of 1979. It intervened in Lebanon in 1958 and again in 1982. American warships protected oil tankers in the Gulf during the Iran-Iraq war. And having pushed Iraq out of Kuwait in 1991, America stayed on in Saudi Arabia to maintain no-fly zones over Iraq. In response to al-Qaeda’s attacks on Washington and New York in September 2001, America invaded Afghanistan in the same year and then Iraq in 2003.

“Lots of countries have strange borders,” says Rami Khouri of the American University of Beirut. “Yet for Arabs, Sykes-Picot is a symbol of a much deeper grievance against colonial tradition. It is about a whole century in which Western powers have played with us and were involved militarily.”

BBC RADIO The Making of the Modern Arab World, Tarek Osman, 4 parts

FT Review ‘A Line in the Sand’ by James Barr

TIME Sykes-Picot: The Centenary of A Deal That Did Not Shape the Middle East

Harvey Morris May 13, 2016

WHAT WAS THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT?

- It was a secret understanding, using 19th century diplomacy, concluded in May 1916 during World War One, between Great Britain and France, with the assent of Russia, for the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire

- The agreement led to the division of Turkish-held Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine into French and British-administered areas. The agreement took its name from its negotiators, Sir Mark Sykes of Britain and Georges Picot of France.

- Implementation saw major changes after WW1 and what did and is still happening in the Middle East.

Go To

The Failures of the International Community in the Middle East since

the Sykes-Picot Agreement, 1916-2016 - by Amb. Freddy Eytan

At ‘The Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs’

Shows original Sykes-Picot map

Contemplating the dirt barrier between Lebanon and Syria

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

THE ANGLO/FRENCH SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT, 1916

|

Why Border Lines Drawn with a Ruler in WW1 |

|

THE SYKES-PICOT MAP

The British-French map above was used in 1916 to,define the British and French spheres of influence after the defeat of the occupying power, Turkey. This helped create the modern Middle East.and defines its borders today.

Straight lines make uncomplicated borders.

At a meeting in Downing Street, Mark Sykes pointed to a map and told the Prime Minister: "I should like to draw a line from the "e" in Acre to the last "k" in Kirkuk."

This is why it had been marked with a chinagraph-pencil

In 1921 80% of its Palestine mandate was given to the Arabs and becsme Transjordan (later renamed Jordan)