|

|

|

|

|

CLICK BUTTON |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Israel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ISRAEL - PALESTINIAN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

ISRAEL HAS A SURPLUS OF OIL

BUT WITH THE POLITICAL STAKES HIGH,

LEADERS GRAPPLE WITH HOW TO PLAY IT

Low prices, environmental and political considerations taken into account as country decides whether to exploit natural resource

The Independent, Clifford Krauss, Saturday 6 July 2019

Israel's energy dilemma is captured in the northern coastal city of Hadera, where the country's largest coal-fired power station is set to be converted to gas

Israel's energy dilemma is captured in the northern coastal city of Hadera, where the country's largest coal-fired power station is set to be converted to gas ( AFP/Getty Images )

For decades, Israel was an energy-starved country surrounded by hostile, oil-rich neighbours.

Now it has a different problem. Thanks to major offshore discoveries over the past decade, it has more natural gas than it can use or readily export.

Having plenty of gas is hardly a burden, and it offers a cleaner-burning alternative to Israel’s longtime power sources. But it presents challenges for a country that wants to extract geopolitical and economic benefits from a rare energy windfall, including building better relations with its neighbours and Europe.

Part of the problem is timing. Just as Israel prepares to produce and export large amounts of gas, the United States, Australia, Qatar and Russia are flooding the market with cheap gas. The other is maths: Israel’s 8.5 million people use in a year less than 1 per cent of the gas that has been found in the country’s waters.

ANoble Energy, a Houston-based company that made its first discovery of gas in Israel in 1999, has found more than 30 trillion cubic feet of gas off the country’s coast over the past decade. Some experts say new discoveries could double that.

As a result, Israel is phasing out diesel and coal-fired electricity, replacing it mostly with gas-fired generation and some solar power. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Cabinet is considering banning the import of gasoline and diesel cars starting in 2030 and gradually switching to vehicles fueled by compressed natural gas or electricity.

Israel is also stepping up exports to neighbours like Jordan and Egypt. There are even plans to supply gas to a power plant in the West Bank for Palestinian customers.

Yet these efforts will make only a dent in the country’s reserves.

“We want to export,” said Jacob Nagel, former head of Israel’s National Security Council. “The question is: How much will it cost? Is it possible? How much time will it take?”

For decades, Israel depended on Russia and other sources for fuel, while its industries and homes relied on coal and oil power plants that blanketed its cities with smog. The switch to gas has helped clear the air in cities like Tel Aviv and Haifa that have converted diesel-fueled plants.

Israel’s biggest coal plant — in Hadera, a coastal city — will be converted over the next three years, cutting national coal consumption by 30%. Officials say they expect to eliminate coal use in 11 years.

In Hadera, improvements are already noticeable after gas replaced oil in one part of the plant and officials installed a scrubber, an exhaust-cleaning device. The beach is no longer caked with sticky black tar, and a yellowish tinge on the horizon is gone.

Guy Stansill, a 38-year-old vegetable farmer at the nearby Sdot Yam kibbutz who can see the plant’s chimneys from his kitchen window, hopes it’s for good. His five-year-old son, Tayo, has asthma, but is breathing better now that the plant is reducing its emissions.

“Reducing the coal industry will be better for the air and health,” he said, although he worries about a possible spill from drilling and gas processing offshore.

But his wife, Lee Kush, thinks the country ought to be investing more in renewable energy. “We have so much sun,” she said, “Why use gas at all?”

Israeli metal band makes video against boycott

Israeli officials acknowledge that the gas will compete with cleaner solar energy. But they argue that the plentiful supply of electricity from gas-fired power plants will encourage the use of electric vehicles, reducing pollution.

“Electric cars are a big market for electricity, so at the end of the day, it’s a big market for gas,” said Ofer Bloch, president of Israel Electric, the state utility.

The Israeli government says it is committed to the Paris climate accord and is close to getting 10 per cent of its electricity from renewable sources by next year. Environmentalists say the country could do better.

The Leviathan field, Israel’s largest, will be connected to the mainland by pipeline by the end of the year, and that should speed the use of gas in transportation, which has been minimal so far. Fifteen garbage lorries in Haifa are running on compressed natural gas. The country has imported 59 such buses from China, and has ordered an additional hundred or so.

But because it has a small industrial base and its residential use of gas is limited because of mild winters, Israel needs to export more to take advantage of its energy bounty.

There are many hurdles.

Last year, Noble and the Israeli company Delek Drilling signed a 10-year deal to deliver gas to Egypt by pipeline beginning later this year. Some of that fuel may be re-exported from two Egyptian terminals.

Energy executives say they are optimistic that Egypt’s growing population, now 100 million, will make it a big market and that gas can bring the two neighbours closer even as Egypt, with its own recent large-scale finds, becomes a bigger producer.

The importance of the Egyptian market was underscored by a trip to Cairo in January by Mr Steinitz, the first official visit by an Israeli minister since the 2011 unrest that shook the Arab world. He and representatives of five other Mediterranean countries and the Palestinian Authority met to form an association to coordinate regulations on gas pipelines and trading.

The water crisis that could impact peace in the Middle East

Still, officials acknowledge that doing business with Egypt is risky. A gas pipeline between the countries was sabotaged in 2012.

Israel could seek to sell gas to Asia, where demand is growing, but public opposition has blocked plans for an export terminal on the small, densely populated shoreline.

But some Israeli experts doubt that the country will become a big exporter and would be happy to see the gas remain at home.

“I don’t see anything wrong with leaving the gas for future generations,” said Gal Luft, a former Israeli military officer and an energy expert. “We’re talking about deepwater gas in the most volatile region in the world. So let’s be humble.”

The New York Times

GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT:

AN OIL BOOM IS TRANSFORMING

THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Petrakis is a special correspondent. Special correspondent Noga Tarnopolsky in Jerusalem contributed to this report.

Los Angeles Times, Maria Petrakis, March 12 2019

Reporting from Athens — In 2007, Mathios Rigas spent $1.13 million to buy a near-dormant oil well in Greece with a license that was about to expire. The engineer-turned-banker hired a Venezuelan petroleum chemist, the only person he had met in Greece who knew about oil and gas. He called his company “Energean,” a play on the words energy and the Aegean Sea.

It paid off. The Prinos oilfield, Greece’s only oil-producing asset, held more reserves than thought and is now producing thousands of barrels a day. In 2016, armed with the experience, Rigas placed another bet and bought the rights to develop the Karish and Tanin natural gas fields off the coast of Israel — a country that bigger oil and natural gas exploration companies were avoiding because it could affect their business with Arab countries or Iran.

Energean now has agreements with Israeli customers for 15 years, securing $12.9 billion in future revenue. The company is now valued at $1.3 billion and has a staff of 385, including the original Venezuelan chemist.

“Converting 1 million euros into a 1-billion-pound company today is, I think, a successful 10-year journey,” said Rigas. “The opportunity to buy into Israel when everybody was busy looking at other opportunities and we were there taking advantage of a fantastic project…. These are eureka moments … when you see opportunity in front of you — we took the risk both times.”

The eastern Mediterranean, better known for strife and conflict, has become a hive of prospecting activity. Israel was once at the mercy of volatile, largely unfriendly neighbors for fuel supplies but now has enough natural gas for itself and to sell to others. Egypt boasts facilities that can process and export natural gas both from its own field, the largest in the region, as well as its new gas-rich neighbors. Tiny Cyprus is grappling with how to best exploit newly discovered natural gas fields off the shores of the long-divided island. And Greece has joined the oil and natural gas search, hoping for another bonanza in its waters after a bruising decade of economic depression.

Israel is the poster child of the natural gas rush that is transforming energy paupers into princes. In 2009, a natural gas field about 50 miles west of the Israeli port of Haifa, dubbed Tamar, was discovered. Then, in 2010, Houston-based Noble Energy Inc. located massive offshore fields 80 miles from Haifa. Named Leviathan, it is a monster of a natural gas field that would not only make Israel self-sufficient but also allow it to export.

The bucolic north of Israel is relatively peaceful for now. »

Greece, Israel, Italy and Cyprus are now set to sign an agreement to build the world’s longest and deepest undersea natural gas pipeline, EastMed, to transport Israeli and Cypriot natural gas to Europe. The project is backed by the European Union, and Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo is expected to push forward the $7-billion project that will help wean Europe off Russian natural gas during a visit to Israel later this month.

“A gas pipeline will run from here and will link us to the gas economy of Europe. It will reach our Arab neighbors,” Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said on Jan. 31 while taking delivery of the foundation of the platform that will pump natural gas from Leviathan. “This is a great revolution — we are turning the state of Israel into an energy power. An independent Israel will not depend on anyone for its energy needs.”

The pipeline is turning out to be an important factor in a new regional alliance involving Greece, Cyprus and Israel even as so many other international alliances are fraying. The nations’ leaders have held five trilateral meetings in the last three years and are already talking about pursuing another energy initiative to connect their power grids — the EuroAsia interconnector undersea cable — and establishing a permanent agency in Nicosia to oversee joint projects.

But the region’s longstanding rivalries may be stubborn obstacles to the vision to feed Israeli natural gas to Europe.

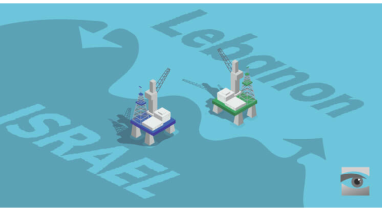

Lebanon on Thursday warned that the planned EastMed pipeline from Israel to the European Union must not be allowed to violate its maritime borders. Beirut has an unresolved maritime border dispute with Israel — which it regards as an enemy — over a sea area of about 330 square miles.

Pompeo is set to visit Beirut as part of his tour of the region, and Netanyahu said the secretary of State will help with Israel’s plan to build the pipeline.

Lebanon has its own plans to seek hydrocarbons, and last year licensed a group comprising Italy’s Eni, France’s Total and Russia’s Novatek to carry out the country’s first offshore energy exploration in two blocks, including one containing waters disputed with Israel.

In the last decade, Greece plunged into the financial abyss, dragging Cyprus with it. Israel and Turkey, formerly close allies, spent much of the last decade mired in ongoing tension after the killing by Israeli commandos of 10 Turkish activists on board a ship that was part of a flotilla attempting to deliver aid to Palestinians in the Gaza Strip in 2010. Greece, a longtime rival of Turkey, is now trying to step into the breach between Israel and Turkey.

The Arab Spring sparked revolts against authoritarian leaders, resulting in a migration of refugees to Europe through Greece and Italy. Egypt temporarily tipped into turmoil in 2011 with the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak, who had safeguarded the 1979 peace treaty with Israel.

But as on-the-ground politics and alliances remain up in the air, what lay below the seas of the eastern Mediterranean has become more clear.

The Tamar field’s significance hit home in 2011, as unrest spread through Egypt. In the Sinai desert, militants frequently attacked the pipeline carrying natural gas from Egypt to Israel and Jordan, crippling supplies.

Israelis waited and worried about the natural gas that they needed to produce nearly half of their electricity. The price of electricity rose 20%. In April 2012, the Egyptian government called a halt to supplies altogether in a spat with Israel over nonpayment for the sputtering supply.

But by then, Tamar was poised to begin supplying the Israeli market with its own natural gas. And the Leviathan field found in 2010 contained an estimated 22 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, enough for the domestic market and exports. Netanyahu called it a “gift of God.”

There were other discoveries: In 2011, Noble Energy discovered the field off Cyprus and another last year. The massive Zohr field off Egypt was located in 2015 and, as the largest thus far, galvanized the interest of international oil companies in the region.

For Europeans, the Israeli experience of 2011-12 is familiar. In 2009 a natural gas dispute between Russia and transit country Ukraine left many EU countries with severe shortages. A pipeline such as EastMed, running from Israeli natural gas fields to Cyprus, then Crete, through mainland Greece and to the heel of Italy, would lessen Europe’s reliance on Russian natural gas.

The EU imports more than half of all the energy it consumes. Many countries are heavily reliant on a single supplier for natural gas, including some that rely entirely on Russia. This dependence leaves them vulnerable to supply disruptions.

The EastMed pipeline would cost an estimated $7 billion, take as many as seven years to build and pose an engineering and technical challenge, with pipe to be laid in extremely deep waters.

To make the pipeline viable more natural gas finds are still needed, as most finds thus far have already been contracted to the region. Analysts say, however, that there are an array of alternatives to the pipeline if needed. Egypt, for example, has two plants that can liquefy natural gas so it can be transported by ship and provide an export outlet to Europe and Asia.

“Politicians love big, flashy projects and the photo ops they present,” said Nikos Tsafos, an analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “But in the end, governments can only do so much — the market needs to support this project. So far, it’s not clear that this is the case.”

A pipeline to Turkey from Israel and via Cyprus could be more commercially viable, allowing natural gas to get to Turkey, a major market, and then possibly onward to the EU. But the lingering tensions between Turkey and Israel, as well as the four-decade conflict over the occupation of northern Cyprus by Turkish troops, make such a pipeline unfeasible for the present.

Talks to unify the island have foundered repeatedly and Turkey generally objects to the internationally-recognized Republic of Cyprus in the south of the island drilling for oil and natural gas, saying that Cyprus’ resources are jointly owned by Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

In February 2018, the Turkish navy blocked a drill ship belonging to Italian company Eni from reaching its destination in Cypriot waters, a reminder of the sort of tension that can occur at any time in the region.

Nevertheless, the natural gas rush has led to some political reconciliation. Israel was included in the first meeting of the East Mediterranean Gas Forum in Cairo in January, alongside the Egyptians, Jordanians and Palestinians as well as the Greeks and the Cypriots.

It was the first visit by an Israeli minister since 2011 and, Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz said, “the first meaningful economic cooperation between Israel and Egypt since the peace treaty was signed in 1979.”

While natural gas has smoothed over some divisions in the region, a legacy of volatility remains. That may be the biggest argument for building a pipeline to Europe, a massive, wealthy and stable customer and ally.

“The region’s politics are always unpredictable,” said analyst Tsafos. “Having more options is always better.”

GAS AND FOREIGN POLICY:

HOW ISRAEL IS LEVERAGING ENERGY

Ezra Friedman writes that the discovery of gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean has given Israel, long perceived as sidelined on the international stage, new avenues to pursue foreign policy objectives: to create energy self-sufficiency, enhance regional stability within the Eastern Mediterranean region, and normalise relations between Israel and its Arab neighbours.

Download a PDF version here.

Fathom, December 2019

The discovery of gas is transforming the geopolitics of the Eastern Mediterranean. Israel, long reliant on energy imports to meet national domestic energy consumption, is set to become not only energy self-sufficient but also an exporter, on a regional and – just maybe – international scale. This is changing Israel’s relations with many of its Eastern Mediterranean neighbours, and providing clear opportunities for advancing geostrategic objectives.

Historically, Israel was seen as an energy starved, constantly in conflict with its oil-rich neighbours. Following the initial discovery of the ‘gas giant’ Tamar in 2009 by an American-Israeli consortium, the Jewish state has found several other ‘gas giants’ which contain tens of trillions cubic meters in proven natural gas reserves. While estimates vary, it is safe to say that Israel has tens of trillions of proven natural gas reserves within its Exclusive Economic Zone and potentially tens of trillions more that could be discovered.

Israel’s solidification of the ‘Tripartite Alliance’ with Greece and Cyprus, in the face of increasingly aggressive policies by a revisionist Turkey, is becoming a stabilising fixture in the region. This is enhancing cooperation on a host of critical economic and security issues for Israel, while also providing Jerusalem with critical advocates within the European Union (EU). The formation and integration of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF) with Israel, Egypt, Cyprus, Greece, Jordan, and the Palestinian Authority (PA) is creating the necessary diplomatic space to facilitate a competitive and sustainable regional gas market. The EMGF is providing Israeli gas with export opportunities to its neighbours while increasing regional economic interdependence. Both of these developments present Israel, a country long perceived as sidelined on the international stage, with several unique avenues to pursue foreign policy objectives in the Eastern Mediterranean region, Europe, and the broader Middle East.

It is essential to frame Israel’s objectives within the context of ‘energy diplomacy’ in the Eastern Mediterranean basin. First, to leverage the discovery and subsequent development of natural gas to create energy self-sufficiency and increased economic opportunities in international energy markets. Second, in tandem, to enhance regional stability within the Eastern Mediterranean region through economic interdependence between regional states, thereby facilitating economic activity. Lastly, to normalise relations between Israel and its Arab neighbours.

HOW NATURAL GAS COULD BE A GEOPOLITICAL GAME-CHANGER IN THE MIDEAST

France 24 (text linked to video 12 May 2017)

It's a discovery that could easily shake up the geopolitical order in the Middle East. Deep under the eastern Mediterranean lies the largest natural gas basin ever found on Europe's doorstep. But the gas fields often coincide with disputed borders between rival nations. Our reporter Marine Pradel investigated this lucrative resource, which everyone wants a piece of.

The billions of cubic metres of natural gas discovered in recent years off Israel, Egypt and Cyprus form what is now called the "Levantine Basin", the largest natural gas reservoir within easy reach of Europe.

The first major deposit, known as Tamar, was discovered in 2009 off the coast of Haifa, Israel, by a consortium made up of Noble Energy (US) and Delek-Avner (Israel). Other gas fields were later discovered in the same zone of the "Levantine Basin": Leviathan (Israel), Aphrodite (Cyprus), but most importantly Zohr, in 2015 off the coast of Egypt: the largest gas field ever discovered in the Mediterranean, larger than all the others combined. It was found by the Italian oil giant ENI, which has already started to exploit it and is aiming to start production by the end of 2017.

Meanwhile, Israel, supported by its US ally, is drilling away, driven by a free-market and idealistic vision: exploiting the gas will oblige the countries of the region to co-operate as business partners, which will in turn create peace and stability.

But the gas under the Mediterranean Sea may also carry within it the seeds of new conflicts. On the divided island of Cyprus, it threatens reunification efforts. In Lebanon, its location - straddling the disputed maritime boundary with Israel - boosts the belligerent rhetoric of the armed Hezbollah group.

It is hoped the gas could be worth billions of dollars, and all eyes are on the highly coveted European gas market, which Russia would like to keep for itself.

Speaking to FRANCE 24 in Washington, the US Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs summarised the situation. “All of a sudden, it’s not just a bunch of fishermen that care about those waters. Suddenly, there’s billions and billions of dollars”, he explained. The stakes are certainly high. In total, nearly 3,500 billion cubic metres of natural gas could lie under the eastern Mediterranean, according to a study by the US Geological Survey.

From Egypt to Syria via Lebanon, Israel and Cyprus, our reporter investigated this precious resource, a double-edged sword that awakens old Cold War reflexes and could well upset the geopolitical order of an already unstable region.

UNDERSTANDING THE ISRAEL-LEBANON

MARITIME BORDER DISPUTE

HonestReporting, Griffin Judd, August 4 2019

GO TO VIDEOS, CHARTS OIL AND GAS

TO SEE CHART SHOWING BORDER ACCORDING TO ISRAEL

AND BORDER ACCORDING TO LEBANON

Inter national border disputes are very common, and in the normal course of events rarely draw any attention. But what happens when one of the countries in the dispute refuses to acknowledge the other’s existence? This complicates things, because the two countries then cannot negotiate directly. After all, negotiation implies recognition.

national border disputes are very common, and in the normal course of events rarely draw any attention. But what happens when one of the countries in the dispute refuses to acknowledge the other’s existence? This complicates things, because the two countries then cannot negotiate directly. After all, negotiation implies recognition.

That is the dilemma currently facing Israel and Lebanon, who, since 2011, have been arguing over an 856 sq km piece of ocean.

But why is this area of the sea worth fighting about? What are the problems? And more importantly, what are the possible solutions?

HISTORY OF THE ISRAEL-LEBANON MARITIME DISPUTE

To understand this dispute, one must understand the international laws behinds it. At the root of the problem lies the jurisdiction of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Under this treaty, states are entitled to a 200-nautical mile Economic Exclusion Zone (EEZ) off their coast. Within this zone, states have exclusive rights to exploit natural resources, such as fish and oil.

Lebanon ratified UNCLOS and submitted its proposed border to the UN in 2011; Israel never ratified the treaty, but generally adheres to it, and submitted its proposed border to the UN at the same time.

AND HERE THE DISPUTE AROSE.

Lebanon does not recognize Israel as a country, and has no diplomatic relations with it. Instead, Lebanon refers to Israel as “the state of Palestine” when submitting treaties to the UN, and the two countries must rely on third parties when concluding negotiations. Israel and Lebanon’s land border (sometimes referred to as the Blue Line) is based on the 1949 armistice agreement and the British-French Paulet-Newcombe Agreement which demarcated the boundary between Mandatory Palestine and Mandatory Syria and Lebanon.

The UNCLOS and Paulet-Newcombe treaties are the foundation of all subsequent Israeli-Lebanese border negotiations.

ISRAEL-LEBANON MARITIME BORDER DISPUTE

Both Lebanon in 2007 and Israel in 2010 concluded maritime border agreements with Cyprus. Lebanon, during its negotiations with Cyprus, marked the southernmost point of its border as Point 1. However, Lebanon was forced to cancel the agreement under pressure from Turkey (meaning it never entered into force). This provided a precedent for Israel, which during its negotiations with Cyprus used Point 1 to indicate its northernmost border.

Lebanon, meanwhile, submitted to the UN borders which were different from those used in its Cyprus negotiations. Point 23, and not Point 1, would be considered the southernmost point of Lebanon’ s EEZ, a difference of 17 km. It’s not clear why the Lebanese altered their demarcation, though some believe the Lebanese wanted to antagonize Israel.

Whatever the reason, this resulted in the overlap between Israel and Lebanon’s claimed EEZs.

WHY DOES IT MATTER?

If the disputed zone was just empty ocean, the Israel-Lebanon maritime border dispute would be a non-issue. However, Israel’s coastal waters contain reserves of oil and natural gas. It is speculated that the waters off Lebanon do as well, with reserves extending into the disputed zone.

THE STAKES ARE HIGH.

Estimates based on seismic studies suggest Lebanon’s EEZ may contain up to 25 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas, an enormous windfall worth billions of dollars for a state whose economy has lagged in recent decades. However, there is also an element of geopolitical danger, as Lebanon seeks to assert its sovereignty at the cost of Israel’s. Indeed, the dispute only rose in prominence in 2018, when Lebanon began selling drilling permits for “blocks” of its EEZ; A combined venture by Total, ENI, and Novatek purchased rights to explore Blocks 4 and 9, the latter of which contains part of the disputed zone.

The Israeli defense minister at the time, Avigdor Liberman, called the move “very provocative,” and the dispute quietly simmered for a year and a half until April, 2019, when Lebanese officials indicated a willingness to negotiate over the zone. Facilitated by the US, direct talks were expected to begin in July, 2019. However, that month an Israeli naval vessel entered the disputed waters, an act deemed a provocation by the Lebanese government.

Lebanese officials hope to avoid geopolitical complications interfering with the exploitation of their resources, an issue which the Palestinian Authority has complained of previously. In 1999, the PA cooperated with Royal Dutch Shell to drill in the Gaza Marine gas field. However, Shell withdrew from the partnership in 2018 following almost two decades of political difficulties — much of it stemming from Hamas’ rule of the Gaza Strip and the blockade upheld by Israel and Egypt.

Related reading: The Gaza Blockade: An Explainer

WHAT’S BEING DONE?

In the absence of direct relations between the two countries, resolving the Israel-Lebanon maritime border dispute is tricky. However, president Barack Obama sent several mediators to try resolving the dispute. According to the Lebanese Middle East Strategic Perspectives website:

The first mediator, Frederic Hof presented a plan in May 2012 creating a provisional but legally binding maritime separation line and a buffer zone with no petroleum activities. According to media reports, it acknowledged that around 500 sq km of the disputed area belong to Lebanon. It didn’t satisfy Beirut but was neither approved nor officially rejected at the time.

A second US mediator, Amos J. Hochstein, proposed a plan more favorable to Lebanon. But the plan never took off due to Lebanese government instability and Israel’s lack of enthusiasm for it.

The Trump administration — notorious for its undermanned diplomatic staff — allowed the issue to simmer until Lebanon signaled it was ready to renew talks in April 2019. Since then, US envoy David Satterfield had been working to set the terms for the July conference, and it had been suggested that a possible solution to the Israel-Lebanon maritime border dispute would open both countries’ waters for seismic surveying. It is unclear whether or not this conference took place.

An agreement on the Israel-Lebanon maritime border could create economic growth for both states and an opportunity for further détente.

Failure, on the other hand, only perpetuates the status quo, benefitting no one.

TENSIONS CONTINUE OVER LEBANON'S PLANS

FOR OIL AND GAS EXPLORATION.

Israel claims the proposed site is within its waters, but Lebanon rejects that assertion has says it will use "all available means" to protect its rights.

AP Archive (text linked to video 16 Feb 2018)

STORYLINE:

A concrete wall under construction on the Israel-Lebanon border: a symbol of the deep divide between the two neighbours.

But tensions are increasingly centred on the sea, not the land.

Lebanon has recently signed a deal with an international consortium to start exploratory offshore drilling for oil and gas.

The agreement is with three oil companies - Italy's Eni, France's Total and Russia's Novatek.

But Israel claims it owns the area.

Earlier this week, Israeli Defense Minister Avigdor Lieberman described Lebanon's exploration tender as "very provocative" and suggested that Lebanon had put out invitations for bids from international groups for a gas field "which is by all accounts ours."

Cesar Abi Khalil, Lebanese Minister of Energy and Water, responds by calling the statement "an aggression on Lebanese sovereignty".

There are over 800 square kilometres (300 square miles) of waters claimed by the two nations. The dispute is over parts of Lebanon's block 9 that is on the border with Israel.

"Our border existed and was demarked before Israel demarked its border and before it launched its aggression on us," says Khalil.

"Block 9 is 100 percent Lebanese."

He says they will use "all available means to protect our petroleum rights".

Lebanon and Israel are technically at war and both countries have fought several wars over the past decades.

The United Nations Interim Forces in Lebanon (UNIFIL) works along the border area.

UNIFIL spokesman Andrea Tenenti says their mandate is to "prevent escalation and to preserve security in the South of Lebanon".

"We do not have a role in delineating the maritime borders," he adds.

He says the border issue has been raised with the UN.

General Amine Htaite worked on the demarcation line between Lebanon and Israel.

He claims they followed the angle of the land border to determine Lebanese waters and says the process was "very accurate".

"Today Israel is trying to impose something on the ground by claiming two things: first the Naqoura point is a disputed area and this is not correct, and second it is trying to deviate the border line so it will own areas in the territorial water."

Subsequent to its withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000, Israel unilaterally installed a line of buoys in the Naqoura area intended as a boundary line at sea between Israel and Lebanon.

While Israel treats the line of buoys as a de facto maritime boundary, there is no agreement between Israel and Lebanon on the delineation of their maritime boundaries.

Lebanon and Israel are technically at war and both countries have fought several wars over the past decades.

ISRAEL, LEBANON AND FAILED NATURAL GAS NEGOTIATIONS

Foreign Policy Research Institute, Leah Pedro, December 11 2019

Over the past decade, there has been a gas revolution in the Eastern Mediterranean, where discoveries of large offshore gas deposits have set up some of the littoral states—notably Israel, Egypt and perhaps Cyprus—as potential significant players in the European natural gas market. This has led to the creation of the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF), set up in Cairo this year, to facilitate cooperation among members—Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, and Palestine, with U.S. support. Lebanon has been late to join in the gas market and has not yet been able to join the EMGF, and Turkey has been excluded for contentious bilateral relationships among members. While there seems to be a chance that further gas deposits are located in Lebanese waters, further exploration and exploitation cannot take place near the Israeli and Lebanese marine border until the contested area is demarcated. The potential profits from oil exploration in the disputed area could bring in as much as US$600 billion over the next several decades. Economic and political possibilities would seem attractive enough to incentivize both sides toward finding common ground. Yet, negotiations to delimit the maritime boundary, set to begin late summer 2019, never came to fruition, and do not seem likely to begin any time soon.

DETERMINING A MARITIME BORDER

GO TO VIDEOS, CHARTS OIL AND GAS

TO SEE CHART SHOWING BORDER ACCORDING TO ISRAEL

AND BORDER ACCORDING TO LEBANON

Demarcating maritime borders differs slightly among the international community. Lebanon, like most UN member states, is a signatory of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This is a more technical convention than customary international law and line-drawing methods are drawn from a continuation of the land border to determine the exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Since Israel is not a UNCLOS signatory, its drawing method is different, and as a result, its unilateral borders conflict.

Cyprus and Lebanon entered a bilateral agreement compliant with UNCLOS to delimit their maritime border in 2007. Their agreement was never ratified, largely because Turkey denounced all agreements with the Republic of Cyprus and its neighboring countries and Lebanon retreated. Since Lebanon chose not to ratify for political reasons, the agreement was never binding.

In 2009, American company Noble Energy discovered the Tamar field off the coast of Israel, with proven and potential natural gas reserves of 320 billion cubic meters (bcm). Shortly after, the Leviathan field was discovered and found to hold about 600 bcm of reserves. The Leviathan falls in 860 square kilometers of disputed oceanic territory between Israel and Lebanon, where there may well be additional reserves yet to be discovered.

A year after the gas discovery, Lebanon submitted its unilateral border to the UN. The southernmost point of its unilateral submission to the United Nations, was 17km south of the line included in the unratified Cypriot-Lebanese agreement.

Shortly after Lebanon’s unilateral border submission, in 2011, Israel and Cyprus reached an agreement for their maritime border, also conflicting with the unratified bilateral agreement between Cyprus and Lebanon. Also, in July 2011, Israel submitted to the UN its own unilateral maritime coordinates, bordering Lebanon. Since then, developments toward negotiating have been minimal at best until this past year, when rumors spread of talks taking place.

ISRAEL’S PERSPECTIVE

Regardless of other incentives related to operations in the contested territory, Israel is likely looking first from a security standpoint. Challenges to the secure transport and stability of gas are not new; energy self-sufficiency has been prioritized by the government: in 2013, Israel placed into effect a law requiring that 60 percent of the gas produced would be for domestic use, with the remaining 40 percent available for export. Though the decision may not have been appreciated by interested international oil companies, Israel remained solid on protecting the bulk of its reserves to ensure its own energy independence, while also recognizing the significance of global market participation.

With the Tamar discovery, Israel had enough of a surplus to ensure domestic energy needs, allowing it to utilize its own natural gas rather than depend on imports from Egypt. The mammoth Leviathan discovery supplied an incentive greater than self-sufficiency, it offered strategic and economic power. The opportunity for self-sufficiency and for a better position vis-à-vis regional and international actors became increasingly attractive. The Leviathan field falls partially within the area contested with Lebanon, and, until an agreement is reached, Israel will face security threats by Hezbollah as well as commercial complications arising from the risk involved for customers in purchasing gas from contested sources.

LEBANON’S PERSPECTIVE

The economic opportunities brought from exploration activities could bring some relief to a tumultuous Lebanon. Venturing into the natural gas industry will likely provide the Lebanese with a number of benefits: gaining a new and important source of income, partnering with other international companies, strengthening bilateral relations, deepening participation in the global market, and increasing governmental legitimacy. As long as negotiations are stalled, the country will face very limited opportunities in the Mediterranean and will likely remain excluded from participating in the EGMF. Thus, it will likely fall behind as the region adapts to the new geopolitical and economic environment. Lebanon’s not coming to an agreement not only means it will miss out on benefits seen by other states, but also that the country may be less likely to improve diplomatic relationships in the region.

Recent developments in Lebanon highlight its economic crisis: protesters have been demanding change in Beirut. Rationed access to U.S. dollars began earlier this month amid further taxes imposed on Lebanese citizens aimed at alleviating stress from the government deficit. A natural gas deal would perhaps alleviate some of the pressure from the population to address economic concerns of the private and public sector, and could provide the necessary boost to the government to ease tensions. Such bleak potential could not have been the ideal outcome for Beirut, but there were political factors that seemed more important to some members of the Lebanese negotiating party.

THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY

Incentives to negotiate do not outweigh the political costs of reaching common ground necessary for talks to begin. Movement towards an agreement has been sluggish for more than a decade. Sources with first-hand knowledge of the negotiations identify a few challenges impeding negotiations. These include the U.S. acting “lazily” as mediator; Lebanon’s insistence on completing negotiations on the land border (especially the disputed Shebaa farms)[1] and skepticism of the U.S. favoring Israel; and Israel’s wariness regarding members within the opposing negotiating team. Among the justifications of delay appears to be a common problem: Hezbollah. Without Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri—the head of the Shiite Amal party and a key Hezbollah ally—approving the terms, Beirut cannot move forward. Of the 30 ministers in the government, 18 align with Hezbollah. The terrorist organization’s power extends to parliament, too, where Speaker Berri and more than half of the seats belong to the Hezbollah camp.[2] The U.S. is therefore limited to continued shuttle diplomacy between the two parties. Meanwhile, the further into disarray Lebanon falls, the further it increases exposure to political risk and makes the prospect of energy deals more remote.

The United States has served as the primary mediating party throughout all previous attempts at negotiations. First was Frederic Hof, the initial mediator beginning in May 2012 when attempts at talks first began. Hof created the “Hof Line” as a proposed compromise, using the UNCLOS delineation tactics. The proposal Hof put forth would have given about 500 km2 of the disputed area to Lebanon (roughly a 55/45 split). It was noted that the “Hof Line” was likely to be supported by Israel, but it was rejected by Hezbollah due ultimately to the group’s political goal of pushing Israelis out of Shebaa Farms. Bundling land and oceanic borders has been Hezbollah’s insisted position, and Israel has made clear its present interest lies only with negotiating the maritime border.

Hof stepped down in September 2012 and was followed by U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Energy Diplomacy Amos J. Hochstein. Hochstein held the position until the conclusion of the Obama administration in 2016. He furthered efforts to use the Hof Line, but was unable to get both sides to the table.

David Satterfield, the former Acting U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, was the prominent mediator assuming leadership with during Trump administration. There is little information regarding Satterfield’s efforts in negotiations prior to March 2019. This could be because shuttle diplomacy is conducted in private. Now that Satterfield is the Ambassador to Turkey, the new U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs is David Schenker, who has taken over as mediator.

Lebanon voiced concerns of distrust of the U.S. as a mediator, citing its stance on Hezbollah (which the U.S. defines as a terrorist organization) and strong bilateral relationship with Israel. A March meeting between Satterfield and Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri showed progress towards a consolidated position from Lebanon, and, weeks later, talks were set to be held under the auspices of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). As the White House was gearing up for the June 26 Bahrain conference, the status of negotiations on the Israel-Lebanon maritime border may have been overstated to play up U.S. power and influence in the region.

LOOKING AHEAD

An agreement could foster a friendlier relationship between the two neighbors, stabilize current domestic-level problems, integrate both parties further into the global market, and enrich both countries.

Tensions have grown between Hezbollah and Israel over the past year, nearing levels not seen since their 34-day border war in 2006. The previous approach of the Israeli government to maintain deniability regarding military operations against Hezbollah and Iran in Syria and Lebanon has been altered in recent months by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and Israel has laid bare its multifaceted efforts to combat Hezbollah. This approach may garner Israel political support, but will also attract attention from allies of Hezbollah and therefore sharpen security vulnerabilities.

Lebanon’s economic situation has been in a reconstruction phase since the 15-year civil war ended in 1990. The public distrust of Lebanese government has not subsided in the years since and worsened with the influx of Syrian refugees. Worsened by the incapacity to create much-needed economic and social reform, class disparities and inequality deepened among the population. Government debt relative to gross domestic product (GDP) continues to grow, reaching 151% of GDP in 2018. Economic collapse will occur if something drastic doesn’t happen soon, and it appears the same is true for the social and political environment in the country. This type of collapse would create a power vacuum in Lebanon and lead to destabilization of an unstable region once again.

It seemed as though there was once a moment where an agreement on the disputed sea might take place, gas exploration could have helped both sides, and steps toward peace seemed closer. The window of opportunity on reaching consensus is likely closed, and things are certainly looking like they will get worse before getting better. The panic in Lebanon and increasing tensions between Hezbollah and Israel have made the maritime agreement less relevant and less attainable.

LEBANON SIGNS DEAL WITH INTERNATIONAL GROUP

FOR EXPLORATORY OFFSHORE DRILLING

AP Archive (text linked to video 17 Feb 2018)

Leah Pedro, a fall 2019 intern at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, is a graduate student in the Center for Global Affairs at New York University, where she studies Transnational Security.

(9 Feb 2018) Lebanon on Friday signed a deal with an international consortium to start exploratory offshore drilling for oil and gas, amid ongoing tensions with Israel.

Beirut hopes that oil and gas will help boost its struggling economy.

The signing ceremony was held on Friday afternoon in Beirut and was attended by President Michel Aoun and officials from the three oil companies, Italy's Eni, France's Total and Russia's Novatek.

The agreement came two months after Lebanon's government approved the licenses for the international consortium to move forward with offshore oil and gas development.

The three companies have bid for two of Lebanon's 10 offshore blocks, to determine whether oil and gas exist.

One of the blocks is disputed in part with Israel.

Lebanon's Foreign Minister Gibran Bassil warned Israel not to try hinder the drilling on the Lebanese side saying that Beirut can also stop offshore development on the Israeli side.

There are over 800 square kilometres (300 square miles) of waters claimed by the two countries.

The dispute is over parts of Lebanon's block 9 that is on the border with Israel.

"Israel cannot stop the activities on the Lebanese side because Lebanon can then stop the activities on the Israeli sides," Bassil told The Associated Press when asked if the drilling will cause more tensions with Israel.

Israel is developing a number of offshore gas deposits, with one large field, Tamar, already producing gas, and the larger Leviathan field set to go online next year, and it has in recent days escalated its threats against Lebanon over Lebanon's invitation for offshore gas exploration bids on the countries' maritime border, claiming that Lebanon will be drilling in areas owned by Israel.

Lebanese officials deny the Israeli statements saying the area where the country plans to drill belongs to Lebanon.

Stephane Michel, President of Total Middle East and North Africa said the drillings in block 9 will be 25 kilometres north of the border with Israel.

"We will drill in 2019 and we will know within a few months if we actually find gas or not. Then, depending on the nature of the discovery, if there is one, we will know how to appreciate it and develop it if it is commercial," Michel said.

Walid Nasr, chairman of the Lebanese Petroleum Administration, the office under the ministry of energy dedicated to the new oil and gas initiative, said it will require at least five years for the country to start producing oil or gas.

ISRAEL-HAMAS UNDERSEA GAS SPAT IN FULL SWING

Discoveries of undersea gas in the Eastern Mediterranean, an area straddling Egyptian, Israeli, Lebanese and Cypriot waters, have reignited old debates about who will reap the rewards.

The Palestinians have a claim too.

DW Jo Harper 12 July 2019

Traditionally, the international energy majors that partner big Arab firms have hesitated to do business with Israel. But as Israel and Persian Gulf states find common cause against Tehran, this seems to be changing.

But to complicate matters, the Palestinian Authority also claims rights to Israel's gas deposits 30 kilometers (19 miles) off its shore.

"The fields are entirely within Palestinian territorial waters, as defined by the Oslo Accords," Tareq Baconi, Crisis Group's analyst for Israel/Palestine and Economics of Conflict, told DW. "So in international law, Palestinians should have full sovereignty in determining how they use their own natural resources."

DW contacted the Israeli energy ministry for comment but has received no reply.

Israel Grenze Gazastreifen Zaun (picture-alliance/dpa/J. Hollander)

An Israeli soldier patrols near the Gaza Strip border with Israel. Gaza relies on Israel to meet almost all its energy needs

THE FINDS

The discovery of a large gas field, Tamar, off the coast of Israel in 2009 opened up a new era for the Eastern Mediterranean as an energy hot spot.

At the time, the gas field was the most prominent field ever found in the subexplored area of the Levantine Basin, which covers about 83,000 square kilometers.

Read more: Gas, pipeline dreams and gunboat diplomacy in Mediterranean

Several alternatives are being considered by Egypt, Cyprus and Israel to transport the energy to markets in Europe and one of two options will likely happen: the expensive and technologically complex EastMed pipeline or developing Egypt's LNG facilities.

Israel and the US are pushing for the EastMed pipeline. The EU is seeking new sources to diversify away from Russia, as internal production falls and demand is set to spike, and the region is close, gas-rich and relatively cheap — or could be.

The Eastern Mediterranean is estimated to have about 2,100 billion cubic meters (bcm) of so far untapped gas. The EU's consumption was 458.5 bcm in 2018 and 465.7 bcm in 2017, according to BP Stats Review 2019.

EastMed would be a 2,200-kilometer pipeline that would pass under the sea base of the islands of Cyprus and Crete and connect to Europe in Greece.

"But EastMed is a technically difficult project, and politically it is made more complicated by the role of Turkey and the Cypriot waters through which it would have to go," Tim Boersma, director of Global Natural Gas Markets at Columbia University's SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy, told DW.

ISRAEL, CYPRUS AND GREECE LEADERS

President of Cyprus Nicos Anastasiades (r), Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (c) and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (l) meeting in May 2018

PALESTINE AT THE BACK OF THE LINE

There are several large projects in the US' recently unveiled $50 billion plan for Israeli-Palestinian peace, including $1 billion in grants, loans and private sector financing for the development of a natural gas field offshore of Gaza. The gas field, Gaza Marine, is owned by the Palestine Investment Fund (PIF).

PIF Chief Executive Officer Mohammad Mustafa told The National in April that it normally takes two to three years to develop it [an offshore gas field]. "Assuming no political difficulties, we hope to be able to start next year," he said.

Gaza Marine is estimated to hold up to a trillion cubic feet of gas, equivalent to Spain's consumption in 2016, according to the US Energy Information Administration. The project is expected to generate revenues of around $2.4 billion (€2 billion) in royalties and taxes over its life, estimated to be 15 years.

At present, the West Bank and Gaza rely on Israel to meet almost all their energy needs, and the Palestinians pay about $2 billion a year to Israel to cover their energy needs.

So the development of the field would be "transformational," according to Robin Mills, chief executive of Qamar Energy.

CROSSED LINES

British Gas (BG Group) and its partners had originally been granted oil and gas exploration rights in a 25-year agreement signed in November 1999 with the PA. A precondition of the deal was that surplus gas would be supplied to Israel. Tel Aviv refused to enter into a deal and the problems started, although with relatively small finds at that stage, the issue was just one of many in the ensuing Israel-Gaza conflict.

In 2018, Shell relinquished its 55% stake in the field that it took over as part of its acquisition of BG Group in 2016. PIF then became the field's sole owner. It is searching for an operator and buyer for a 45% stake.

"The PA doesn't decide unilaterally on projects like this, and if Israel gets even the slightest whiff of Hamas gaining financially from this kind of precept, it will pull the plug," says Boersma. "As Kushner's plan rightly suggests, there is a huge potential upside to Israel-PA collaboration. But it is conditioned on there being peace, and there is no peace."

Plans for the development of Gaza Marine predate Israel's discovery of its own gas reserves, Baconi says. "Israel's opposition to the development of the field, now couched in security arguments, predate Hamas's takeover of the Gaza Strip," Baconi says.

"Israel has an economic incentive to ensure Palestinians remain reliant on Israeli energy, as a captive market, then develop their own resources," Baconi says.

PUTIN IN THE WINGS?

In January Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas met with Russian President Vladimir Putin to officially sign an investment agreement aiming to develop the Gaza offshore gas field. AFP reported that there was talk of Russia investing $1 billion

ISRAEL, SAUDI ARABIA DISCUSSED GAS DEALS

Countries looked into gas pipeline from Eilat to Saudi Arabia,

Energy deals would require formal diplomatic relations

Bloomberg Yaacov Benmeleh and Anthony Dipaola 1 August 2019, — With assistance by Donna Abu-Nasr, and Vivian Nereim

Saudi Arabia has looked into buying Israeli natural gas, according to a former member of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s cabinet, the latest sign of warming ties between two formally hostile nations.

The countries have discussed building a pipeline that would connect Saudi Arabia to Eilat, Ayoob Kara, citing conversations with “senior officials” in the region, said in an interview in Jerusalem. Eilat, the Israeli city that banks the Gulf of Aqaba and is about 40 kilometers (24.9 miles) from the border, was chosen for its proximity to Saudi Arabia.

An energy project of this magnitude would require formal diplomatic relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia and is likely to elicit political pushback. Israel remains largely unpopular in the Arab world for its treatment of Palestinians, who live under occupation in the West Bank and under siege in Gaza. Israel and Saudi Arabia have united behind closed doors in their antagonism toward Iran but formalizing an alliance may still be hard to achieve.

Kara, a former communications minister, has been one of Netanyahu’s closest advisers on relations with Arab countries and was among a handful of Israeli cabinet members to appear publicly in a Gulf state in the past year. “This is about mutual interest,” he said.

Representatives for the energy ministries in Israel and Saudi Arabia didn’t respond to requests for comment. The Saudi Information Ministry’s Center for International Communication also didn’t respond.

Read more: How Do Israel’s Tech Firms Do Business in Saudi Arabia? Very Quietly

Israeli companies found massive quantities of gas in Israeli waters about 10 years ago but have struggled to realize the fuel’s potential. The partners developing Israel’s biggest reservoir have signed $25 billion in contracts but still have more than 80% of the reservoir untied to any buyers. Saudi Arabia could help to fill that gap: The kingdom plans to invest more than six times that amount in gas over the next decade, in part to meet rising demand for cheaper electricity.

REGIONAL OPPOSITION

Geopolitics could get in the way. Mass demonstrations broke out in Amman in 2016 after the companies developing Israel’s biggest offshore gas fields signed a $10 billion contract with Jordan, home to millions of Palestinian descent. That project should see the first flows of gas by the end of the year.

While some Saudis argue that normalizing relations with Israel is a natural merging of interests, many others vehemently oppose the idea. Public resistance is so strong that a group of more than 2,000 citizens from different Gulf countries circulated an online petition last year “to stop all forms of normalization with the Zionist entity.” They signed their full names -- a rare step in a region where freedom of expression is limited.

While leaders of the Arab world used to be united behind the Palestinians, that support began to wane because of the strains between Iran and Sunni Gulf countries, Kara said. Saudi Arabia and its regional allies now pay “lip service” to the Palestinian cause, and are seeking upgraded military and economic ties with Israel to counter Iran, he said.

“All they care about is the security and future of their countries,” he said.

Part of the discussions between officials center on a new energy corridor that would connect Saudi Arabia to the Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline in Israel. This would allow the kingdom to export its oil to Europe and markets further west while skirting a sea route where the U.S. has accused Iran of carrying out several attacks against commercial ships, Kara said.

Set up in 1968, Eilat-Ashkelon Pipeline Co. was then jointly-owned by Iran and Israel and facilitated oil exports from Iran to Europe. That relationship ended after Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini rose to power in Tehran in 1979 and he marked Israel as an enemy to the Islamic Republic.

Natural Gas in Israel Times of Israel

Natural Gas: What it Means for Israel and Europe Forbes

EastMed gas: Paving the way for a new geopolitical era? DW 24.06.2019 Sergio Matalucci

Natural gas in Israel - Wikipedia

Petroleum in Israel Wikipedia

Arab Gas Pipeline Wikipedia

Pressure mounts against importing Israeli gas to Jordan Al-Monitor December 10 2019

Israel Science & Technology: Oil & Natural Gas Jewish Virtual Library

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

|

Global Development: |

|

ISRAEL - NATURAL GAS