|

|

|

|

|

CLICK BUTTON |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Israel |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ISRAEL - PALESTINIAN |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PART 1 T O P I C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishWikipedia.info

THE

INCREDIBLE

STORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

EDITORS NOTE: Hajj Amin Al-Husani, the Mufti of Jerusalem who led the Palestinian Arabs in the 1920’s and 1930’s wanted to expel the Jews. His ideas directly determined Arab action before he was expelled by the British in 1937.

Later his ideas were highlighted by his close relationship

to the Nazis and his enthusiasm for the Holocaust Final Solution.

THE 80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION

In 1937, an official British report first proposed the partition of Mandate Palestine. The story behind it helps to explain why the Arab-Jewish conflict remains unresolved.

Mosaic, May 2018

In this epochal year of Zionist anniversaries—the 120th of the First Zionist Conference in Basle, the 100th of the Balfour Declaration, the 70th of the 1947 UN Partition Resolution, the 50th of the Six-Day War—there is yet another to be marked: the 80th anniversary of the 1937 British Peel Commission Report, which first proposed a “two-state solution” for Palestine.

The story of the Peel report is largely unknown today, but it is worth retelling for two reasons:

First, it is a historic saga featuring six extraordinary figures, five of whom testified before the commission: on the Zionist side, David Ben-Gurion, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, and Chaim Weizmann, the leaders respectively of the left, right, and center of the Zionist movement; on the Arab side, Haj Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem; and on the British side, Winston Churchill, who gave crucial testimony in camera. Louis D. Brandeis, the leading American Zionist, also played a significant role.

Second, and perhaps even more important today, the story helps to explain why, a century after the Balfour Declaration, the Arab-Jewish conflict remains unresolved.

The history and prehistory of the Balfour Declaration has been notably covered in anniversary pieces in Mosaic by Martin Kramer, Nicholas Rostow, Allan Arkush, Colin Shindler, and Douglas J. Feith. In November 1917, as Britain fought the Ottoman Turks in the Middle East during World War I, the British foreign secretary, Arthur Balfour, formally declared British support for “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. The Balfour Declaration, as it came to be known, was issued after extensive consideration by the British cabinet and consultation with Britain’s allies, including the United States, whose president, Woodrow Wilson, approved it in October 1917. In 1922, the League of Nations incorporated it into the Mandate for Palestine that the League entrusted to Britain, and the Declaration thereby became an established part of international law.

The Palestinian Arabs rejected both the Balfour Declaration and the League of Nations Mandate, even after Britain in 1923 severed the larger portion of Palestine, east of the Jordan River, and recognized Emir Abdullah of Transjordan as its new ruler. In 1929, Arabs rioted in Jerusalem, massacred Jews in Hebron and Safed, and attacked Jews elsewhere in the land. In 1936, in a substantial escalation, the Arabs called a general economic strike, sabotaged trains, roads, and telephone lines, engaged in widespread violence against Jews, destroyed their trees and crops, and conducted guerrilla attacks against the British Mandate authorities.

In May 1936, the British announced their intention to establish a commission to “ascertain the underlying causes of the disturbances” and make recommendations for the future. Arab violence continued through October, delaying the arrival in Jerusalem of the commission, led by Lord Peel, until November. While it was on its way, the Arabs declared they would boycott its proceedings.

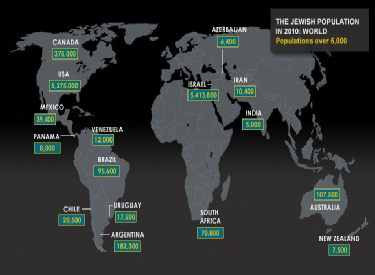

Recognizing that the future of their national home was at stake, the Jews presented to the commission a major defense of the Zionist cause: a 288-page printed memorandum, together with five appendices, covering the history of Palestine, the legal basis of the Mandate, and the extensive Jewish accomplishments in Palestine in the two decades since the Balfour Declaration. The memorandum emphasized the urgency of the hour—the Nazis had been in power for three years and had stripped German Jews of their civil rights. The memorandum stressed that Jews were “not concerned merely with the assertion of abstract rights” but also with “the pressure of dire practical necessity”:

The conditions now prevailing in Germany are too well known to require lengthy description. . . . But it is not only in Germany that the Jews are living under [such] conditions. . . . About five million Jews . . . are concentrated in certain parts of eastern and southeastern Europe . . . for whom the visible future holds no hope. The avenues of escape are closing. . . . What saves them from despair is the thought [of the Jewish national home].

Weizmann, Ben-Gurion, and Jabotinsky testified before the commission between November 1936 and February 1937. Taken together, their presentations constituted the most forceful and eloquent defense of Zionism since Theodor Herzl convened the First Zionist Congress 40 years earlier. Weizmann’s two-hour presentation was perhaps the finest in his long career as head of the Zionist Organization. The “six million people . . . pent up in places where they are not wanted,” he said, faced a world “divided into places where they cannot live and places into which they cannot enter.” The Jews sought but “one place in the world . . . where we could live and express ourselves in accordance with our character, and make our contribution to civilization in our own way.”

Ben-Gurion’s testimony was, if anything, even more forceful. The rights of the Jews in Palestine, he reminded the commission, were derived not from the Mandate and the Balfour Declaration but from the history chronicled in the Bible:

[T]he Bible is our Mandate, the Bible which was written by us, in our own language, in Hebrew, in this very country. . . . Our right is as old as the Jewish people. It was only the recognition of that right which was expressed in the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate. . . . [We are] re-establishing a thing which we had, which we held, and which was our own during the whole history of the Jewish people.

Jabotinsky’s turn came at the commission’s last public hearing, held in London on February 11, 1937. The London newspapers reported that “hundreds of Jews queued up outside the House of Lords” to hear his testimony, and “more people [were] turned away than could be admitted.” Notables in the audience included William Ormsby-Gore (the new secretary of state for the colonies) and Lady Blanche Dugdale (Lord Balfour’s niece). Jabotinsky, the foremost orator among the Zionists, spoke of the urgent imperative of rescue:

We have got to save millions, many millions. I do not know whether it is a question of re-housing one-third of the Jewish race, half of the Jewish race, or a quarter of the Jewish race . . . but it is a question of millions. . . . It is quite understandable that the Arabs of Palestine would prefer Palestine to be the Arab State No. 4, No. 5, or No. 6—that I quite understand—but when the Arab claim is confronted with our Jewish demand to be saved, it is like the claims of appetite versus the claims of starvation.

In additional testimony delivered in camera, Weizmann also addressed Arab demands. In his view, the Arabs would not be satisfied with anything less than eliminating the Mandate altogether. “They got three kingdoms”—namely, Syria, Iraq, and Transjordan—“out of the [world] war,” he said, and now “they begrudge us whatever we have today in Palestine.” Referring to the mufti, he warned that this was a leader who “does not want a single Jew to come in” and that further British concessions to him would be counterproductive:

[T]he whole history of the Mandate, and of the Balfour Declaration, is a history of whittling down . . . of cajoling and coaxing the Arabs into accepting some sort of compromise, and it [has] operated on them exactly in the opposite direction. They [have] said: “If we can by one pogrom, two pogroms, or three pogroms achieve that much, we will bide our time and we shall find the proper moment at which to destroy [the Jews]. . . . [Their position has always been]: “We are against the Balfour Declaration, we are against the Mandate, we cannot discuss it.”

Indeed, that was precisely what the Arabs did say upon canceling their boycott of the proceedings in January and deciding to testify after all. The mufti, appearing as their leader, informed the commission that the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate were wholly invalid, the result of “undue Jewish pressure” on the British government and of a Jewish plan to reconstruct Solomon’s Temple on Arab holy places. Declaring that Palestine was “already fully populated,” he deemed it impossible to accommodate “two distinct peoples” in the same country—a point on which the commissioners then interrogated him more closely:

Q. [I]f the Arabs had [a state in Palestine], would they be prepared to welcome the Jews already in the country?

A. That will be left to the discretion of the government which will be set up. . . .

Q. Does His Eminence think that this country can assimilate and digest the 400,000 Jews now in the country?

A. No.

Q. Some of them would have to be removed by a process kindly or painful as the case may be?

A. We must leave all this to the future.

On March 12, 1937, Winston Churchill, appearing in camera, forcefully confirmed to the commissioners the underlying vision of the Balfour Declaration. “[C]ertainly it was contemplated and intended,” he said, “that [the Jews] might in the course of time [establish] an overwhelmingly Jewish state” in Palestine, and that this “great Jewish state” might be “numbered by millions.” Churchill pleaded with the commissioners: “Do not be diverted from your purpose.”

In the months after the commission completed its hearings, its members began considering a partition of Palestine. Weizmann had been queried about such an idea during his private appearances before the commission. He had responded that he couldn’t comment officially, but that he personally thought it might offer a way forward.

On June 8, 1937, a month before the commission’s report was released, Sir Archibald Sinclair, the head of the British Liberal party, hosted a dinner for Weizmann and the key pro-Zionist British leaders of all parties: Winston Churchill, Clement Attlee, Leopold Amery, Josiah Wedgwood, and James de Rothschild. A secret memorandum summarizing the dinner conversation recorded that Churchill, along with all the other British guests except Amery, had expressed a “very emphatic disapproval” of the whole partition idea:

[Churchill] warned those present that the [British] government was untrustworthy. . . . [Under partition,] the Jewish state would not materialize; the Arabs would immediately start trouble, and the government would run away again. With this proposal, they were incubating a bloody war. The only thing the Jews could do was persevere, persevere, persevere!

The memorandum noted both Weizmann’s diplomatic response to Churchill—namely, that the partition plan was “the only way out which seemed to commend itself to the commission”—and Churchill’s emphatic rejoinder: “the whole thing [is] a mirage . . . and the Jews must hang on.”

On July 7, 1937, the British Cabinet released the Peel Commission Report. Its 435 pages traced the 3,000-year Jewish connection to Palestine; found that building the Jewish national home had been advantageous to the Arabs, who had benefited from the investment of Jewish capital and Jewish economic activity in Palestine; noted the very large increases of the Arab population in Jewish urban areas, as contrasted with virtually no growth in Arab towns such as Nablus and Hebron; observed that Jewish hospitals and clinics served both Arabs and Jews; and recognized that Jewish anti-malaria efforts throughout Palestine had aided everyone.

As for the ongoing Arab revolt, its underlying cause, the report concluded, was the implacable Arab opposition to the Jewish presence in Palestine. The Arab leaders’ views had “not shifted by an inch from that which they adopted when first they understood the implications of the Balfour Declaration.” Instead, the Arabs were continuing to “deny the validity of the Balfour Declaration [and] the right of the Powers to entrust a Mandate to Great Britain.” And these views were enforced from the top. Indeed, the report stated, the “ugliest element in the picture” was not terrorism against Jews—“attacks by Arabs on Jews, unhappily, are no new thing”—but attacks by Arabs on Arabs who were suspected of insufficient adherence to the mufti’s views.

In that connection, the report cited an example: the visit by gunmen to “the editor of one of the Arabic newspapers last August shortly after he had published articles in favor of calling off the ‘strike’” initiated by the mufti. And that visit was hardly an isolated event:

Similar visits were paid during our stay in Palestine to wealthy Arab landowners or businessmen who were believed to have made inadequate contributions to the fund which the [mufti’s] Arab Higher Committee were raising to compensate Arabs for damage suffered during the “disturbances.” Nor do the “gunmen” stop at intimidation. It is not known who murdered the Arab acting mayor of Hebron last August, but no one doubts that he lost his life because he had dared to differ from the “extremist” policy of the Higher Committee. The attempt to murder the Arab mayor of Haifa, which took place a few days after we left Palestine, is also, we are told, regarded as political.

In short, the commission found, Arab nationalism in Palestine, rather than arising from “positive national feeling,” was “inextricably interwoven with antagonism to the Jews.” Thus, even if the Jewish national home were “far smaller, . . . the Arab attitude would be the same.” Nor could Arab “moderates” facilitate a peaceful settlement, since on major issues they invariably ended up siding with the extremists. All in all, therefore, the commission was “convinced that no prospect of a lasting settlement can be founded on moderate Arab nationalism. At every successive crisis in the past that hope has been entertained. In each case it has proved illusory.”

Given the commission’s findings, what was to be done? In 1923, capitulating to Arab rejection of the Balfour Declaration, Britain had already ceded to the Arabs all of Palestine east of the Jordan River, territory that had originally been intended to be part of the Jewish national home. Now, in the face of the commission’s own candid acknowledgment of the Arabs’ continued intransigence and murderous intentions toward the Jews, the British cravenly proposed yet another act of pro-Arab appeasement.

This renewed capitulation was expressed in the commission’s partition plan, intended to replace the Mandate for a Jewish national home with a minuscule Jewish state. The Arabs, already in possession of all of Palestine east of the Jordan River, would now be further rewarded with most of Palestine west of it as well. The city of Jerusalem, with a corridor to the Mediterranean represented in green on the map alongside, would continue to be controlled by the British. As for the Jews, they would be restricted to a “dwarfish area” (to quote Jabotinsky’s apt description)—a crowded coastal principality that would leave no room for further Jewish immigration.

Source: Jewish Virtual Library.

The reaction of pro-Zionist British public figures to the Peel Commission report was scathing. David Lloyd George—who had been prime minister at the time of the Balfour Declaration—called it “scandalous” and “a lamentable admission” of British failure. Viscount Herbert Samuel, the British high commissioner for Palestine in the 1920s, harshly criticized it in the House of Lords. In the Commons, Winston Churchill, Archibald Sinclair, and James de Rothschild all categorically opposed partition.

In America, Louis D. Brandeis urged Zionists to oppose the partition plan with all their might. In a July 26, 1937 letter to Felix Frankfurter, his close friend and fellow Zionist, Brandeis related that Josiah Wedgwood, one of the pro-Zionist British party leaders who had attended the dinner with Weizmann, had said that “Weizmann was selling us for a mess of porridge, and that at a dinner held not many days before, several Christian members of Parliament had told [Weizmann] so in unmistakable language.”

In his 1949 autobiography, Weizmann would write that with the Peel Commission report, “Arab terrorism had won its first major victory,” having succeeded in getting the British to declare that the Mandate was unworkable. It was “hard to describe,” he wrote, “the heartsickness and bitterness of the Jews as they watched the larger Hitler terror engulf their kin in Europe, while the gates of Palestine were being shut as a concession to the Arabs.” In 1937, however, he believed the offer of Jewish state should be seized, even if it would be much smaller than the national home envisioned at the time of the Balfour Declaration.

In his address to the Twentieth Zionist Congress in Zurich, which opened three weeks after the Peel Commission report was issued, Weizmann rejected the commission’s specific plan but urged the 484 delegates to approve the idea of partition, which he called “a revolutionary proposal.” He told the delegates that “If the proposal opens a way [to a Jewish state], then I, who for some 40 years have done all that [lies within] me, who have given all to the movement, then I shall say Yes, and I trust that you will do likewise.” The ever-shrewd Ben-Gurion also supported partition, believing a small Jewish state could be expanded later, one way or another.

The ensuing debate was the most contentious since 1903, when the Sixth Zionist Congress had rejected Herzl’s proposal for a Jewish state in Uganda. The American delegation opposed partition, as did the Jews living in the Arab lands of the Middle East, as well as various delegates sympathetic to Jabotinsky. The Congress finally voted 300-158 in favor of a resolution directing its leaders “to resist any infringement of the rights of the Jewish people internationally guaranteed by the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate,” but expressing “the readiness of the Jewish people to reach a peaceful settlement with the Arabs of Palestine” and authorizing further negotiations on a partition plan. Implicitly, the Zionist movement had accepted a two-state solution.

As for the Arabs, they dismissed the Peel Commission report out of hand. They would not recognize any Jewish sovereignty whatsoever in Palestine, no matter how dwarfish the area. Arab violence continued for the next two years, until Britain issued a new “White Paper” in 1939, withdrawing its previous partition proposal and pledging, in a breathtaking breach of its Mandate obligation, to convert Palestine instead into a single Arab-majority state. In the hope of further mollifying the Arabs, the British proceeded to impose draconian new restrictions on Jewish immigration, promising to phase it out entirely, and severe restrictions on any future Jewish purchases of land.

Three months after the issuance of the White Paper, World War II broke out in Europe. During 1940, Weizmann, Jabotinsky, and Ben-Gurion each undertook a mission to America, seeking support for a Jewish army to join the fight against Hitler. For his part, Haj Amin al-Husseini went to Nazi Germany to discuss plans to bring the war to Palestine as soon as possible. In 1941, he reached a secret agreement with Hitler to work together in what they called a “common cause”: the elimination of the “Jewish element” in Palestine.

Following World War II, the Palestinian Arabs rejected a two-state solution once again in 1947 (UN Resolution 181), and then, even after the state of Israel’s creation, rejected it three times more: in July 2000 (Israel’s Camp David offer), in January 2001 (the Clinton parameters), and in September 2008 (the Olmert offer). Palestinian negotiators have long been instructed never to use the phrase “Jewish state,” “homeland for the Jewish people,” or any similar phase that might recognize Jewish sovereignty anywhere in historical Palestine.

In his 2016 address to the UN General Assembly, the Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas demanded that Britain apologize for the Balfour Declaration, and he reiterated that position in his address to the UN on September 25 of this year. He has repeatedly asserted (in 2011, 2014, and 2016) that he will “never” recognize a Jewish state.

Eighty years after the first proposal for a two-state solution, even “moderate” Palestinian Arab leaders still reject its basic premise. They want a Palestinian state, but not if the price is recognition of a Jewish state. On that issue the Palestinian position, to use the language of the Peel Commission report, “has not shifted by an inch.”

BELIEF IN PALESTINIAN OPENNESS

TO TWO-STATE SOLUTION AMOUNTS TO INSANITY

Rather than look at the historical record of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and draw the self-evident conclusions, Uri Avnery retreats into the counterfactual fantasyland.

Jerusalem Post, Efraim Karsh, November 21, 2017,

director of the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, is emeritus professor of Middle East and Mediterranean studies at King’s College London and editor of the Middle East Quarterly.

- Top US congressman: Time to think beyond two-state solution

- Egyptian Ambassador to Israel: Chaos will break out without peace with the Palestinians

I never thought I would concur with anything written by veteran Israeli “peace” activist Uri Avnery, but I find myself in full agreement with his recent prognosis that “sheer stupidity plays a major role in the history of nations” and that the longstanding rejection of the two-state solution has been nothing short of grand idiocy.

But it is here that our consensus ends. For rather than look at the historical record of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and draw the self-evident conclusions, Avnery retreats into the counterfactual fantasyland in which he has been living for decades. “When I pointed this out [i.e., the two-state solution], right after the 1948 war,” he writes, “I was more or less alone. Now this is a worldwide consensus, everywhere except in Israel.”

Ignoring the vainglorious (mis)appropriation of the two-state solution by the then 25-year-old Avnery, this assertion is not only unfounded but the inverse of the truth. Far from being averse to the idea, the Zionist leadership accepted the two-state solution as early as 1937 when it was first raised by a British commission of inquiry headed by Lord Peel.

And while this acceptance was somewhat half-hearted given that the proposed Jewish state occupied a mere 15% of the mandate territory west of the Jordan river, it was the Zionist leadership that 10 years later spearheaded the international campaign for the two-state solution that culminated in the UN partition resolution of November 1947.

Likewise, since the onset of the Oslo process in September 1993, five successive Israeli prime ministers – Shimon Peres, Ehud Barak, Ariel Sharon, Ehud Olmert and Benjamin Netanyahu – have openly and unequivocally endorsed the two-state solution. Paradoxically it was Yitzhak Rabin, posthumously glorified as a tireless “soldier of peace,” who envisaged a Palestinian “entity short of a state that will independently run the lives of the Palestinians under its control,” while Netanyahu, whom Avnery berates for rejecting the two-state solution, has repeatedly proclaimed his support for the idea, including in a high-profile 2011 address to both houses of the US Congress.

By contrast, the Palestinian Arab leadership, as well the neighboring Arab states have invariably rejected the two-state solution from the start. The July 1937 Peel Committee report led to the intensification of mass violence, begun the previous year and curtailed for the duration of the commission’s deliberations, while the November 1947 partition resolution triggered an immediate outburst of Palestinian-Arab violence, followed six months later by an all-Arab attempt to destroy the newly proclaimed State of Israel.

Nor was the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), established in 1964 at the initiative of Egypt’s president Gamal Abdel Nasser and designated by the Arab League in 1974 as the “sole legitimate representative” of the Palestinian people, more receptive to the idea.

Its hallowed founding document, the Palestinian Covenant, adopted upon its formation and revised four years later to reflect the organization’s growing militancy, has far less to say about Palestinian statehood than about the need to destroy Israel.

In June 1974, the PLO diversified the means used to this end by adopting the “phased strategy,” which authorized it to seize whatever territory Israel was prepared or compelled to cede and use it as a springboard for further territorial gains until achieving, in its phrase, the “complete liberation of Palestine.” Five years later, when president Carter attempted to bring the Palestinians into the Egyptian-Israeli peace negotiations, he ran into the brick wall of rejectionism.

This is a lousy deal,” PLO chairman Yasser Arafat told the American Edward Said, who had passed him the administration’s offer.

“We want Palestine. We’re not interested in bits of Palestine. We don’t want to negotiate with the Israelis. We’re going to fight.” Even as he shook prime minister Rabin’s hand on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993, Arafat was assuring the Palestinians in a pre-recorded Arabic-language message that the agreement was merely an implementation of the PLO’s phased strategy.

During the next 11 years, until his death in November 2004, Arafat played an intricate game of Jekyll and Hyde, speaking the language of peace to Israeli and Western audiences while depicting the Oslo accords to his subjects as transient arrangements required by the needs of the moment. He made constant allusions to the phased strategy and the Treaty of Hudaibiya – signed by Muhammad with the people of Mecca in 628 CE, only to be disavowed a couple of years later when the situation shifted in the prophet’s favor.

He insisted on the “right of return,” the standard Palestinian/Arab euphemism for Israel’s destruction through demographic subversion; he failed to abolish the numerous clauses in the Palestinian Covenant that promulgated Israel’s destruction; and he indoctrinated his Palestinian subjects with virulent hatred toward their “peace partners” and their claim to statehood through a sustained campaign of racial and political incitement unparalleled in scope and intensity since Nazi Germany.

He didn’t stop at incitement, either – he built an extensive terrorist infrastructure in the territories under his control and, eventually, resorted to outright mass violence, first in September 1996 to discredit the newly elected Netanyahu and then in September 2000, shortly after being offered Palestinian statehood by Netanyahu’s successor, Ehud Barak, with the launch of his terror war (euphemized as the “al-Aksa Intifada”) – the bloodiest and most destructive confrontation between Israelis and Palestinians since 1948.

This rejectionist approach was fully sustained by Arafat’s successor, Mahmoud Abbas, who has had no qualms about reiterating the vilest antisemitic calumnies and has vowed time and again never to accept the idea of Jewish statehood. At the November 2007 US-sponsored Annapolis peace conference he rejected prime minister Olmert’s proposal for the creation of a Palestinian state in virtually the entire West Bank and Gaza that would recognize Israel as a Jewish state.

When in June 2009 Netanyahu broke with Likud’s ideological precept and agreed to the establishment of a Palestinian state provided it recognized Israel’s Jewish nature, PLO chief peace negotiator Saeb Erekat warned that “not in a thousand years will Netanyahu find a single Palestinian who would agree to the conditions stipulated in his speech,” while Fatah, the PLO’s largest constituent organization and Abbas’s alma mater, reaffirmed its longstanding commitment to the “armed struggle” as a strategy, not tactic, “...until the Zionist entity is eliminated and Palestine is liberated.”

As late as November 2017 Abbas demanded that the British government apologize for the 1917 Balfour Declaration – the first great-power public acceptance of the Jewish right to national self-determination.

Can this 80-year-long recalcitrance be considered outright, unadulterated idiocy? It most certainly can. Had the Palestinians accepted the two-state solution in the 1930s or 1940s, they would have had their independent state over a substantial part of mandate Palestine by 1948, if not a decade earlier, and would have been spared the traumatic experience of dispersal and exile.

Had Arafat set the PLO on the path to peace and reconciliation instead of turning it into one of the most murderous and corrupt terrorist organizations in modern times, a Palestinian state could have been established in the late 1960s or the early 1970s; in 1979, as a corollary to the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty; by May 1999, as part of the Oslo process; or at the very latest, with the Camp David summit of July 2000. Had Abbas abandoned his predecessors’ rejectionist path, a Palestinian state could have been established after the Annapolis summit, or during Barack Obama’s presidency.

Avnery’s failure to see this stark historical record for what it is, and his unwavering belief in Palestinian openness to the two-state solution, may not qualify as idiocy, yet surely conforms to Albert Einstein’s famous definition of insanity: doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

BORDERLINE VIEWS:

SEEKING ALTERNATIVES TO THE TWO-STATE SOLUTION

Is it possible to envisage some form of power sharing between two peoples, one within each maintains its own national status?

Jerusalem Post DAVID NEWMAN MARCH 7, 2016

The writer is Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences and professor of geopolitics at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The views expressed are his alone.

- Borderline views: The Antiquities Authority’s campaign against pluralism at the Western Wall

- Borderline Views: Im Tirtzu, rightist NGOs cause damage to Israel's image

Tomorrow’s conference at Ben-Gurion University, hosted by the Haim Herzog Center for Middle Eastern Studies, will focus on alternative paths to resurrecting peace scenarios beyond the traditional two-state solution.

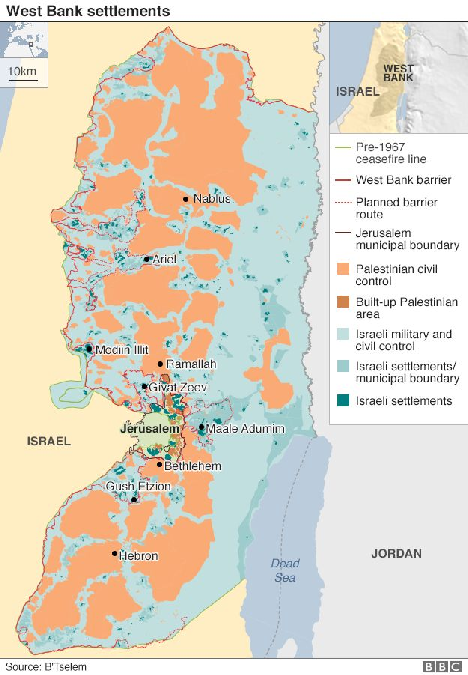

During the past 20 years the notion of two independent states, separated by a single physical border along, or in close proximity to, the Green Line separating Israel from the West Bank, has become the commonly accepted mantra for an eventual resolution of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Many hours of discussions and back-room negotiations have been spent trying to demarcate a border which would be acceptable, or perhaps equally unacceptable, to both sides, taking into account such critical issues as settlements, potential land swaps, security considerations and demilitarization, as well as creating some form of territorial corridor linking the Gaza Strip to the West Bank, for as long as the two disconnected areas continue to be considered part of a single solution.

There have, of course, always been opponents of the two state scenario – from both sides of the political spectrum. On the Israeli far Right, and increasingly within the present government, there are groups, especially among the settler movement and in the world of religious Zionism, who are in principle opposed to the idea of anything but Jewish sovereignty between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River. The establishment of settlements, which commenced shortly after the Six Day War in 1967 and which has continued unabated since that time, was designed to prevent any form of Israeli territorial withdrawal.

Despite the hiccup of the Oslo process along the way, the settlers can claim to have achieved their goal, bringing almost 400,000 residents to the regions (not including east Jerusalem ) and making it almost impossible for any Israeli government, even of the Left, to undertake a forceful evacuation of these communities without bringing about a civil war. Today, senior ministers within the Likud government, such as Ze’ev Elkin and Education Minister Naftali Bennett, are outspoken in their opposition to a two state solution and have even suggested the formal annulment of the Oslo Agreements.

On the far Left, as well as in many Palestinian circles, there has also been opposition to a two state solution, opting instead for a single binational secular democracy between the Mediterranean and the Jordan in which all Jews and Arabs have equal citizenship and in which power is shared, through a process of full democracy and equality, between the different religious and ethnic groups residing in the territory. This solution rejects the notion of nation states, be they Jewish or Arab. Its implementation would mean the end of the State of Israel as a Jewish state and is therefore opposed by the vast majority of Jewish residents of Israel, including those on the Left who believe that Israel should withdraw from the West Bank and allow the Palestinians to have their own state, precisely because they desire to maintain a state within which there is an overwhelming Jewish majority.

As such, the two state solution has never been perceived as constituting anything other than the least bad option. Since the alternatives – the continuation of occupation and the extension of Israeli sovereignty over all the region (the far Right), or the annulment of the State of Israel and the establishment of a single binational state in which there would be no self-defined security for the Jewish people (the far Left), the notion of territorial separation has always appeared to be the best option. The two state solution was boosted in the post-Oslo period (although it was never proposed as such in the agreements), and strengthened even further just a decade ago when prime minister Ariel Sharon was in power. His (and his successor Ehud Olmert’s) eventual support of a Palestinian state was pragmatic rather than ideological, accepting the link between security and demography and understanding that a failure to withdraw from the territories would eventually bring about parity between the two populations, resulting de facto in the end of the Jewish majority and the annulment of the Jewish state.

Assuming that Israel indeed desires to continue to be portrayed as a democracy and to grant equal rights to all the people under its control, the alternatives under such a scenario would mean either that the country loses its Jewish majority or that the present system of control continues in a discriminatory fashion, drawing comparisons with other regimes and other periods of history which Israel strongly rejects.

Each of the alternatives outlined above, both of which are rejected by the majority of the Jewish population in Israel, have one characteristic in common. Neither require the demarcation of a border between separate territorial entities, as they both envisage the entire area between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River as constituting a single territorial entity.

But today the two state solution is becoming even more difficult, perhaps impossible, to implement, by the majority who continue, albeit in decreasing numbers, to support it. More and more people, including military experts and diplomats, are reaching the conclusion that it is no longer possible to implement this solution. The conditions on the ground have become far too complicated and it is necessary to seek political and territorial alternatives. As with so many previous opportunities, time has passed us by, changes have taken place, and the two state solution has, for many, become too complicated to implement in practical terms.

One factor which has contributed more than any other to this has been the continued construction and expansion of the settlement network, which means that today no Israeli government, even of a left-wing persuasion (and it is hard to envisage any such government rising to power in the foreseeable future) would be able to forcefully evacuate even a quarter to a third of the settlers who would remain on the “wrong” (Palestinian) side of the new border, even after taking land exchanges into account. These settlements, the heartland of the ideological Gush Emunim-based settlements, would resist any attempt to force them from their homes and would probably draw tens if not hundreds of thousands of supporters to their cause, far beyond anything that was experienced at the time of the withdrawal from the Gaza Strip.

So what, if any, are the alternatives? Is it possible to envisage some form of power sharing between two peoples, one within each maintains its own national status? Can there be a single territory but two political entities – one land two peoples – an idea which is being shopped around at the moment? The idea that the national groups, regardless of their geographical location, would retain citizenship of a single state – Israeli or Palestinian – with a system based on numerous enclaves and exclaves, perhaps cantons under a Swiss-type federal arrangement , is one idea which has been raised. Notions of federalism and confederalism, which were initially discussed as far back as the 1970s, especially by professor Daniel Elazar of Bar-Ilan University, a world expert on federalism, but were largely dismissed at the time as being unrealistic have resurfaced in many of these discussions.

Ironically, they would have been much easier to implement at that time than they would be today.

Any form of arrangement which is non-territorial based seems like a remote dream, even more problematic than what used to be thought of a simplistic exercise in drawing a line on a map. But we need to think beyond the classic territorial box if we wish to break away from the current inertia, accepting that the solutions of the far Right and the far Left remain ideologically unacceptable to the majority, while the physical separation of the two state solution becomes increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to implement.

Time takes on a critical factor, as settlements continue to increase on the one hand, but so too does the demographic gap between the two populations decrease. The right- and left-wing scenarios are taking place before our very own eyes, and without a real alternative the day of reckoning between the extension of Israeli sovereignty or a single binational state will draw ever closer, with the eventual confrontation being even bloodier than anything we have experienced until now.

ISRAEL AND THE PALESTINIANS:

WHAT ARE THE ALTERNATIVES

TO A TWO-STATE SOLUTION?

When President Donald Trump commented "two states and one state - I like the one that both parties like" about an eventual Israeli-Palestinian settlement, it suggested a rethink, and perhaps a downgrading, of the time-honoured "two-state solution" of past US administrations.

But what are the other options?

BBC 17 February 2017

Colin Shindler is emeritus professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. The author of numerous books on Israel, his The Rise of the Israel Right (Cambridge University Press) was awarded the gold medal in The Washington Institute for Near East Policy's 2016 Book Prize competition.

ORIGIN OF PARTITION

To understand where the concept of sharing or dividing this piece of land comes from, it is important to look at its recent past.

Arab nationalism and Jewish nationalism arose during the same period of history with claims to the same territory. This rationale was the underlying basis for an equitable solution, based on partition and a two-state solution.

In 1921, TransJordan (now the state of Jordan) was formally separated from Palestine (now Israel and the West Bank/Gaza). A UN resolution in 1947 proposed a second partition, this time of the territory west of the river Jordan.

One part would be a state where Zionist Jews constituted a majority, the other where the Palestinian Arabs would be a majority of the population, but the latter rejected the idea.

COMPETING CLAIMS

Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, Jordan occupied the West Bank. Egypt in turn controlled Gaza.

During the Six Day War in 1967, Israel defeated Jordanian forces and conquered the West Bank. Similarly Egypt was forced to leave the Gaza Strip.

While the Israeli Left was willing to return territory to Jordan for regional peace, the rise of Palestinian nationalism under Yasser Arafat and the ascendency of the Israeli Right under Menahem Begin initially proposed polarised solutions - either a Greater Israel or a Greater Palestine, but not a two-state solution.

The Israeli Right argued that there were nationalist and religious reasons for retaining the West Bank. Some on the Israeli Left wanted to build socialism on the West Bank through the construction of a network of kibbutzim.

Israeli security experts, meanwhile, believed that the West Bank provided strategic depth to slow down an invading army. All this led to a burgeoning settler movement.

TWO STATES

Yasser Arafat started to move towards a two-state solution after 1974 (though some saw this as a ploy) and established a Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Gaza, following the Oslo Accords with Israel in 1993.

Successive Israeli prime ministers - Ehud Barak, Ariel Sharon, Ehud Olmert and Benjamin Netanyahu - have all accepted the idea of a Palestinian state, but have differed in terms of what it should actually comprise.

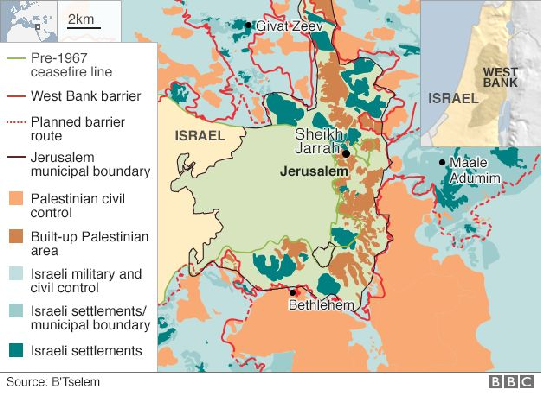

Recent advocates of the two-state solution have suggested an Israeli border near the West Bank barrier, which would encompass a majority of Israeli settlers. This may well be the basis for a plan eventually put forward by the Trump administration.

Despite proclamations of a State of Palestine by Arafat and his successor, Mahmoud Abbas, it has never materialised as a de facto entity, and despite Mr Netanyahu's declaration of support for a Palestinian state in 2009, it is unlikely that any right-wing government would permit its emergence for both ideological and security reasons.

The takeover of Gaza in 2007 by Hamas produced a divided Palestinian Authority. The nationalists controlled the West Bank while the Islamists ruled Gaza.

Yasser Arafat achieved self-rule for Palestinians but no state

In the past decade any reconciliation has been based more on public relations than on public reality. This has led to the idea of two Palestinian states or autonomous areas for the Palestinians.

One fundamental difference between the two sides has been support for a two-state solution by Palestinian nationalists, but no unambiguous statement to this effect from Palestinian Islamists.

Their objection is essentially theological in that the entire territory from the Mediterranean to the River Jordan should be under Islamic rule with no land being ceded.

ONE STATE

A one-state solution is based on the premise that it is highly unlikely that today's 400,000 Jewish settlers in the West Bank will leave voluntarily or be evacuated forcibly.

Those on the Israeli far-left regard such a unitary state as being a state of all its citizens.

However critics on the Israeli side point out that within a few years the number of Palestinian Arabs in the West Bank and Gaza and the number of Arab citizens of Israel itself will have reached parity with the number of Jews in Israel and in the West Bank.

Given that the Arab birth-rate is higher than the Jewish one, if voters vote according to their ethnic origin, then this means the end of Jewish self-determination in their own nation state.

Some on the Israeli far-right favour either a full or partial annexation of the West Bank while restricting democratic rights for the Palestinians.

Meanwhile, an interim solution of a bi-national state would see both national groups working constructively within the same state, but one which offers protection for their political and legal rights and preserves their national identity.

Nationalism however has proved to be a powerful force in recent times with the disintegration of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia into individual nation-states - and some have argued that while a one-state solution is logical in a theoretical sense, the national enmity between Israelis and Palestinians would produce an unworkable entity.

THREE-STATE CONFEDERATION

The idea of a confederation between Israel, Palestine (West Bank/Gaza) and Jordan has been debated ever since 1948.

A former Israeli foreign minister, Abba Eban, vigorously promoted a Benelux-style economic union solution. The Israeli Labour government after the Six Day War adopted variations of a solution known as the Allon Plan, which effectively partitioned the West Bank between Israel and Jordan with remaining territory under local Palestinian autonomy.

However, it was the rise of a Palestinian national identity in the 1970s which scuppered this idea in favour of a Palestinian state. Ever since, both Jordan and Egypt have shown little enthusiasm for reassuming responsibility for the West Bank and Gaza.

AUTONOMY

Former Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin proposed the idea of administrative autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza shortly after coming to power in 1977.

Self-rule for the Palestinians meant that Israel would be responsible for security and foreign policy while ideologically retaining a claim to Judea and Samaria (West Bank).

While limited autonomy was granted under the Oslo peace accords, it was probably viewed by both sides as an interim solution. The demise of the peace process has frozen any further progress.

The eventual shape of a final settlement has therefore yet to be determined

Lord Peel and Sir Horace Rumbold, chairman & vice chairman of the Palestine Royal Commission, after taking evidence from the Arab Higher Committee in Jerusalem in 1937. Library of Congress.

|

Borderline Views: |

Israel and the Palestinians: |

ISRAEL - THE UNRESOLVED TWO STATE SOLUTION